|

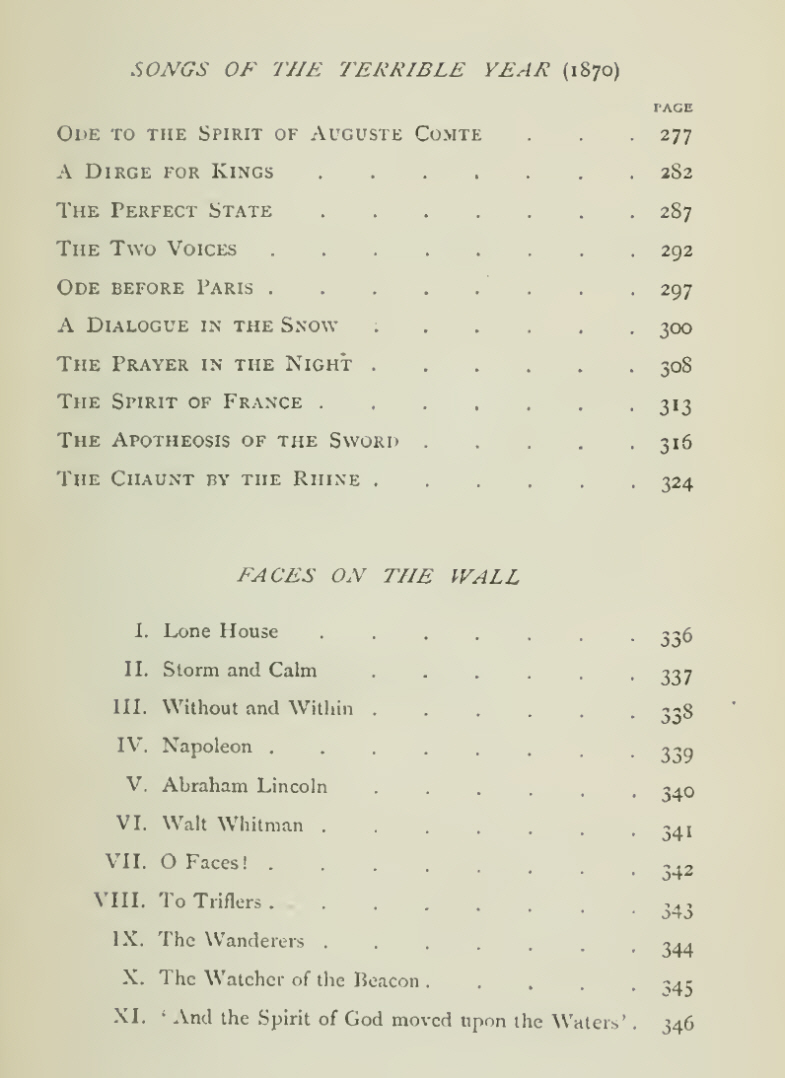

COLLECTIONS (4)

The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan

(3 vols. London: Henry S. King & Co., 1874. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co., 1874.)

Vol. I. continued

BALLADS AND POEMS OF LIFE.

_____

‘I overheard Jove one day,’ said Silenus, ‘talking of destroying the Earth. He said it had failed—they were all rogues and vixens, who went from bad to worse as fast as the days succeeded each other. Minerva said she hoped not: they were only ridiculous little creatures, with this odd circumstance, that they had a blur, or indeterminate aspect, seen far or seen near. If you called them bad they would appear so; if you called them good they would appear so; and there was no one person or action among them which would not puzzle her Owl, much more all Olympus, to know whether it was fundamentally bad or good.’ — R. W. EMERSON.

Stage Manager. Hoity toity! here be death-beds! Every character in thy life-drama dies!

Poet. Wherefore not? What life is complete without its last word? The public are eager, and would behold all.

Stage Manager. But hast thou no fear of being deem’d dull?

Poet. Let the grinning world go elsewhere! I do not disdain true comedy; but the strangest smiles I have seen have been in Death’s eyes. Patience; thou shalt see that the lean Anatomy is the veriest humourist of all.

THIS WORLD AND ANOTHER.

‘Bexhill, 1866’ - from London Poems, 1866. The original version was published in the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works, whereas this is a slightly revised version.

BEXHILL, 1866

BY mother’s side I draw descent

From Saxon squires most excellent,

Fat fellows, innocent of soul,

If lovers of the gaudriole;

By father’s side I heirship trace

To many a seer of Celtic race,

Whose blood, transmitted down to me,

Puts glamour into all I see.

Saxon and Celt, a modern creature,

Dower’d with a kind of double nature;

Eager to laugh, yet never quite

Escaping to the full free light,

Content to brood, yet constantly

Disturb’d by gleams of drollery;

I sing, with contradictions rife,

My modern songs of death and life.

NOW, when the catkins of the hazel swing

Wither'd above the leafy nook wherein

The chaffinch breasts her five blue-speckled eggs,

All round the thorn grows fragrant, white with may,

And underneath the fresh wild hyacinth-bed

Wavers like water in the whispering wind;

Now, on this gentle sunset of the spring,

I sit, within my cottage by the sea,

Thinking of yonder city where I dwelt,

Wherein I sicken'd, and whereof I learn’d

So much that broods like music on my brain.

A melancholy happiness is mine!

My thoughts, like blossoms of the muscatel,

Smell sweetest in the gloaming; and I feel

Visions and vanishings of other years,—

Faint as the scent of distant clover meadows—

Sweet, sweet, though they awaken serious cares—

Beautiful, beautiful, though they make me weep.

The good days dead, the well-belovëd gone

Before me, lonely I abode amid

The buying, and the selling, and the strife

Of little natures; yet there still remain’d

Something to thank the Lord for.—I could live!

On winter nights, when wind and snow were out,

Afford a fire to keep the body warm;

And while I sat, with homeward-looking eyes,

And while I heard the trouble of the town,

I fancied ’twas the sound I used to hear

In Scotland, when I stood beside the Sea.

I knew not how it was, or why it was,

I only heard a sea-sound, and was sad.

It haunted me and pain’d me, and it made

That little life of penmanship a dream!

And yet it served my soul for company,

When the dark city gather’d on my brain,

And from the solitude came never a voice

To bring the good days back, and show my soul

It was not quite a solitary thing.

The purifying trouble grew and grew,

Till silentness was more than I could bear.

Brought by the ocean murmur from afar,

Came silent phantoms of the misty hills

Which I had known and loved in other days;

And, ah! from time to time, the hum of life

Around me, the strange faces of the streets,

Mingling with those thin phantoms of the hills,

And with that ocean-murmur, made a cloud

That changed around my life with shades and sounds,

And, melting often in the light of day,

Left on my brow dews of delicious dream.

And then I sang of Scottish dales and dells,

And human shapes that lived and moved therein,

Close to the seven-days’ Sabbath of the hills.

Thereto, not seldom, did I seek to make

The busy life of London musical,

And phrase in modern song the troubled lives

Of dwellers in the sunless lanes and streets.

Yet ever I was haunted from afar,

While singing; and the presence of the Mountains

Was on me; and the sighing of the Sea

Strengthen’d my mood; and everywhere I saw,

Flowing beneath the blackness of the streets,

The current of sublimer, stronger, life,

Which is the source of human smiles and tears,

And, melodised, becomes the soul of song.

Darkling, I long’d for utterance, whereby

Poor pilgrims might be holpen, gladden’d, cheer’d!

Brightening be times, I sang for singing’s sake!

The wild wind of ambition grew subdued,

And left the changeful current of my soul

Crystal and pure and clear, to glass like water

The sad and beautiful of human life;

Till, even in the unsung city’s streets

Seem’d quiet marvels meet for serious song,

Truths hard to phrase and render musical.

For ah! the weariness and weight of tears,

The crying out to God, the wish for slumber,

They lay so deep, so deep! God heard them all;

He set them unto music of His own;

But easier far the task to sing of kings,

Or weave weird ballads where the moon-dew glistens,

Than body forth this life in beauteous sound.

The crowd had voices, but each living man

Within the crowd seem’d silence-smit and hard;

They only heard the tumult of the town,

They only felt the dimness in their eyes,

And now and then turn’d startled, when they saw

Some weary one fling up his arms and drop,

Clay-cold, among them,—and they scarcely grieved,

But hush’d their hearts a time, and hurried on.

’Twas comfort deep as tears to sit alone,

Haunted by shadows from afar away,

And try to utter forth, in tuneful speech,

What lay so musically on my heart.

But, though it sweeten’d life, it seem’d in vain.

For while I sang, much that was clear before—

The souls of men and women in the streets,

The sounding Sea, the presence of the Hills,

And all the weariness, and all the fret,

And all the dim, strange pain for what had fled—

Turn’d into mist, mingled before mine eyes,

Roll’d up like wreaths of smoke to heaven, and died:

The pen dropt from my hand, mine eyes grew dim,

And the great roar was in mine ears again,

And I was all alone in London streets.

Hither to pastoral solitude I came,

Happy to breathe again serener air

And feel a purer sunshine; and the woods

And meadows were to me an ecstasy,

The singing birds a glory, and the trees

A green perpetual feast to fill the eye

And shimmer in upon the soul; but chief,

There came the wonder of the Waters, sounds

Of sunny tides that wash on silver sands,

Or cries of waves that anguish’d and went white

Under the eyes of lightnings. ’Twas a bliss

Beyond the bliss of dreaming, yet in time

It grew familiar as my mother’s face;

And when the wonder and the ecstasy

Had mingled with the beatings of my heart,

The terrible City loom’d from far away

And gather’d on me cloudily, dropping dews,

Even as those phantoms of departed days

Had haunted me in London streets and lanes.

Wherefore in brighter mood I sought again

To make the life of London musical,

And sought the mirror of my soul for shapes

That linger’d, faces bright or agonised,

Yet ever taking something beautiful

From glamour of green branches, and of clouds

That glided piloted by golden airs.

And if I list to sing of sad things oft,

It is that sad things in this life of breath

Are deepest and divinest. Tears bring forth

The richness of our natures, as the rain

Sweetens the smelling brier; and I, thank God,

Have anguish’d here in no ignoble tears—

Tears for the pale friend with the singing lips,

Tears for the father with the gentle eyes

(My dearest up in heaven next to God)

Who loved me like a woman. I have wrought

No girlond of the rose and passion-flower,

Grown in a careful garden in the sun;

But I have gather’d samphire dizzily,

Close to the hollow roaring of a Sea.

___

‘Meg Blane’ - from North Coast and Other Poems, 1867. The poem was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version of ‘Meg Blane’, with a few minor alterations was then published in the Chatto & Windus 1884 edition of the Poetical Works.

‘Tiger Bay: A Stormy Night’s Dream’ - originally published in Good Words, July, 1871. ‘Tiger Bay’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works.and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘Nell’ - from London Poems, 1866. The poem was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version of ‘Nell’ was then included in the ‘London Poems’ section of the Chatto & Windus 1884 edition of the Poetical Works.

‘The Starling’ - from London Poems, 1866.

‘To The Luggie’ - from North Coast and Other Poems, 1867, where it was entitled ‘The Brook’.

‘Charmian’ - originally published in The Broadway, August, 1867.

CHARMIAN

Cleo. Charmian!

Char. Madam?

Cleo. Give me to drink mandragora!

Antony and Cleopatra.

IN the time when water-lilies shake

Their green and gold on river and lake,

When the cuckoo calls in the heart o’ the heat,

When the Dog-star foams and the shade is sweet;

Where cool and fresh the River ran,

I sat by the side of Charmian,

And heard no sound from the world of man.

All was so sweet and still that day!

The rustling shade, the rippling stream.

All life, all breath, dissolved away

Into a golden dream;

Warm and sweet the scented shade

Drowsily caught the breeze and stirred,

Faint and low through the green glade

Came hum of bee and song of bird.

Our hearts were full of drowsy bliss, [2:9]

And yet we did not clasp nor kiss, [2:10]

Nor did we break the happy spell

With tender tone or syllable.

But to ease our hearts and set thought free,

We pluckt the flowers of a red Rose-tree,

And leaf by leaf, we threw them, Sweet,

Into the River at our feet,

And in an indolent delight

Watch’d them glide onward, out of sight. [2:18]

Sweet, had I spoken boldly then,

How might my love have garner’d thee! [3:2]

But I had left the paths of men,

And sitting yonder dreamily,

Was happiness enough for me!

Seeking no gift of word or kiss,

But looking in thy face, was bliss!

Plucking the Rose-leaves in a dream,

Watching them glimmer down the stream,

Knowing that eastern heart of thine

Shared the dim ecstasy of mine!

Then, while we linger’d, cold and gray

Came Twilight, chilling soul and sense;

And you arose to go away,

Full of a sweet indifference! [4:4]

I missed the spell—I watch’d it break,—

And such come never twice to man:

In a less golden hour I spake,

And did not win thee, Charmian!

For wearily we turned away

Into the world of everyday,

And from thy heart the fancy fled

Like the Rose-leaves on the River shed;

But to me that hour is sweeter far

Than the world and all its treasures are:

Still to sit on so close to thee,

Were happiness enough for me! [5:8]

Still to sit on in a green nook,

Nor break the spell by word or look!

To reach out happy hands for ever,

To pluck the Rose-leaves, Charmian!

To watch them fade on the gleaming River,

And hear no sound from the world of man!

[Notes:

Alterations in the 1882 Selected Poems:

v. 2, l. 10: And yet we did not clasp or kiss,

v. 3, l. 2: Then might my love have garner’d thee!

Alterations in the 1892 The Buchanan Ballads, Old and New:

v. 2, l. 9: Our hearts were full of sleepy bliss,

v. 2, l. 10: And yet we did not clasp or kiss,

v. 2, l. 18: Watch’d them glide onward, slowly, out of sight.

v. 4, l. 4: Full of divine indifference!

v. 5, l. 8: Were Paradise enough for me! ]

___

‘The Scaith O’ Bartle’ - from London Poems, 1866. The poem was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version of ‘The Scaith O’ Bartle’ was then included in the ‘North Coast, and other Poems (1867-68)’ section of the Chatto & Windus 1884 edition of the Poetical Works.

‘Clari In The Well’ - originally published in Good Words, August, 1871.

CLARI IN THE WELL

O MY fountain of a maiden,

Sweet to hear and bright to see,

Now before mine eyes love-laden

Dancing, thrilling, flashing free,—

Still thy sparkling bliss a moment, sit thee down, and look at me.

Gaze into my face, my dearest!

Thro’ thy gleaming, golden hair;

Meet mine eyes—ah! thine are clearest

When my image floateth there;

Now, they still themselves, like waters when the windless skies are fair.

In those depths of limpid azure

See my baby likeness beam!

Deep blue with reflected pleasure

From some heavenly dome of dream,

Crystal currents of thy spirit swim around it, glance, and gleam!

Hold my hand, and heark’ning to me

For a space, be calm and cold.

While that liquid look flows thro’ me,

And I love thee twenty-fold,

I am smiling at a story thy dead mother often told.

When thou wert a little blossom [5:1]

Blown about thy village home,

Thou didst on that mother’s bosom

Put a question troublesome:

‘Mother, please, where did you find me? whence do little children come?’

And the dame with bright beguiling

Kiss’d her answer first, my dear!

But, still prest, she answer’d smiling—

‘In the orchard Well so clear,

Thou wert seen one sunny morning, sleeping, and we brought thee here.’

With a look as grave as this is

Thou didst ponder thoughts profound;

On the next day with fond kisses

Clinging mother’s neck around—

‘Mother! mother! I’ve been looking in the Well where I was found!

‘Bright and clear it is! but—mother!’

(Here thine eyes look’d wonderingly)

‘In the well there is another—

Just the very same as me!—

And it is awake and moving—and its pretty eyes can see!

‘When I stretch my arms unto it,

Out its little arms stretch too!

Apple-blossoms red I threw it,

And it broke away from view—

Then again it look’d up laughing thro’ the waters deep and blue!’

Then thy gentle mother kiss’d thee,

Clari, as I kiss thee now,

With a wondering fondness bless’d thee,

Smooth’d the bright hair from thy brow—

Saying, ‘’Tis a little Sister, happy-eyed and sweet as thou!

‘Underneath the deep pure water

Dwell its parents in green bowers—

Yes, it is their little daughter,

Just the same as thou art ours;

And it loves to lie there, looking at the pleasant orchard flowers.

‘Every day, while thou art growing,

Thou wilt find thy Sister fair—

Even when the skies are snowing

And the water freezes there,

Break the blue ice,—thro’ the water with a cold nose she will stare! [12:5]

‘As thou changest, growing taller,

She will change, thro’ all the years—

Well thou may’st thy Sister call her,

She will share thy hopes and fears,

She will wear the face thou wearest, sweet in smiles and sad in tears.

‘Ah, my darling! may’st thou ever

See her look as kind and bright,

Find her woeful-featured never

In the pleasant orchard light—

May you both be glad and happy, when your golden locks are white!’

Golden locks!—what, these grow hoary?

Wrinkles mar a face like this?

Break the charm of the old story

With the magic of a kiss—

Here thou art, my deep-eyed darling, as thou wert,—a thing of bliss. [15:5]

Does she love thee? does she miss thee?

Thy sweet Sister in the well?

Does she mourn because I kiss thee—

Fearing what she cannot tell?—

For you both are link’d together by a truth and by a spell.

Darling, be my love and duty

Judged by her! and prove me so;

When upon her mystic beauty

Thou perceivest shame or woe;

When she changes into sadness, may God judge, and strike me low!

Thou and thy sweet Sister move in

A diviner element,

Clear as light, more sweet to love in

Than my world so turbulent;

Holy waters bathe and bless you, peaceful, bright, and innocent.

And within those eyes of azure

See! my baby image beam,

Deep blue with reflected pleasure

From some heavenly dome of dream,

Crystal currents of thy spirit swim around it, glance, and gleam.

O my fountain of a maiden,

Be thy days for ever blest,

Dancing in mine eyes love-laden,

Lying smiling on my breast,—

Brighter than a fount, in motion, deeper than a well, at rest.

[Notes:

Alterations in the 1884 edition of The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan:

v. 5, l. 1: When thou wast a little blossom

v. 12, l. 5: Break the blue ice,—thro’ the water with a cold cheek she will stare!

v. 15, l. 5: Here thou art, my deep-eyed darling, as thou wast,—a thing of bliss. ]

___

There follows a sequence of seven poems under the title, ‘LONDON LYRICS’:

‘I. The City Asleep’ - originally published in London Society, March, 1869. ‘The City Asleep’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘II. Up In An Attic’ - originally published in The Argosy, October, 1866. ‘Up In An Attic’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘III. To The Moon’ - originally published in London Society, February, 1868. ‘To The Moon’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘IV. Spring Song In The City’ - originally published in London Society, May, 1868. ‘Spring Song In The City’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘V. To David In Heaven’ - from Undertones, 1863. The original version of ‘To David In Heaven’ in the 1863, Moxon edition of Undertones, was revised for the 1865, Strahan edition. This version was later published in the 1884, Chatto & Windus edition of the Poetical Works. The 1874 King edition of the Poetical Works has this third revision of the poem:

V

TO DAVID IN HEAVEN

‘Quem Di diligunt, adolescens moritur.’

SEE! the slow Moon roaming

Thro’ gray mists of gloaming,

Furrowing with pearl-bright edge the jewel-powder’d sky!

See, the Bridge moss-laden,

Arch’d like foot of maiden,

And on the Bridge, in silence, looking upward, you and I! [1:6]

See, the pleasant season [1:7]

Of reaping and of mowing—

The mournful Moon above—beneath, the River duskily flowing!

Blown from scented meadows,

Violet-colour’d shadows,

Pass o’er us to the pine-wood dark from yonder dim corn-ridge;

The River gleams and gushes

Thro’ shady sedge and rushes,

And gray gnats gather o’er the pools, beneath the mossy Bridge;—

And you and I stand darkly,

O’er the keystone leaning,

And watch the pale mesmeric Moon, in the time of gleaners and gleaning.

Do I dream, I wonder?

As, sitting sadly under

A lonely roof in London, thro’ the grim square pane I gaze?

Here of thee I ponder,

In a dream, and yonder

The sad streets seem to stir and breathe beneath the white Moon’s rays.

By the vision cherish’d,

By the battle bravèd,

Do I but dream a hopeless dream, in the City that slew you, David?

Is it fancy also,

That the light which falls so

Faintly upon the stony street below me, as I write,

Near tall mountain passes

Thro’ churchyard weeds and grasses,

Barely a mower’s mile away from that small Bridge, this night?

And, where you are lying,—

Grass and flowers above you—

Is mingled with your sleeping face, as calm as the hearts that love you?

Poet gentle-hearted,

Are you then departed,

Have you ceased to dream the dream we loved of old so well?

Has the deeply cherish’d

Aspiration perish’d,

And are you happy, David, in that heaven where you dwell?

Have you won the wisdom

We so wildly fought for,

Is your young Soul enswathed, at last, in the singing robes you sought for?

In some Heaven star-lighted,

Are you now united

Unto the poet-spirits that you loved, of English race?

Is Chatterton still dreaming?

To give it stately seeming,

Hath the music of his last strong song flash’d into Keats’s face?

Is Wordsworth there? and Spenser?

Beyond the grave’s black portals,

Can the grand eye of Milton see the glory he sang to mortals?

You at least could teach me,

Could your low voice reach me,

Where I sit and copy out for men my Soul’s strange speech,

Whether it be bootless,

Profitless, and fruitless,—

The weary aching upward strife to heights we cannot reach,

The fame we seek in sorrow,

The agony we forego not,

The haunting singing sense that makes us climb—whither we know not!

Must it last for ever,

The passionate endeavour,

Ay, have you, there in heaven, hearts to throb and still aspire?

In the life you know now,

Render’d white as snow now,

Doth a fresh mountain-range arise, and beckon higher—higher?

Are you dreaming, dreaming,

Is your Soul still roaming,

Still gazing upward as we gazed, of old, in the autumn gloaming!

Upward my face I turn to you,

I long for you, I yearn to you,

The spectral vision trances me to utt’rance wild and weak;

It is not that I mourn you,

To mourn you were to scorn you,

For you are one step nearer to the secret Singers seek.

But I want, and cannot see you,

I seek, and cannot find you,

And, see! I touch the Book of Songs you tenderly left behind you!

Ay, me! I bend above it

With tearful eyes, and love it,

With tender hand I touch the leaves, but cannot find you there!

My sad eyes ever and only

Behold that gloaming lonely,

The shadows on the mossy Bridge, the glamour in the air!

I touch the leaves, and only

See rays which they retain not—

The Moon that is a lamp to Hope, who glorifies—what we gain not!

The aching and the yearning,

The hollow undiscerning,

Uplooking want I still retain, darken the leaves I touch—

Pale promise, with much sweetness

Solemnizing incompleteness,

But ah! you knew so little then—and now, you know so much!

By the vision cherish’d,

By the battle bravëd,

Have you, in Heaven, shamed the song, by a mightier music, David?

I, who loved and knew you,

In the City that slew you,

Still hunger on, and thirst, and climb, proud-hearted and alone:

Serpent-fears enfold me,

Syren-visions hold me,

And, like a wave, I gather strength, and, gathering strength, I moan;

Yea, the pale Moon beckons,

Still I follow, aching,

And gather strength, only to make a louder moan, in breaking!

Tho’ the world could turn from you,

This, at least, I learn from you:

Beauty and Truth, tho’ never found, are worthy to be sought;

The Singer, upward-springing,

Is grander than his singing,

And tranquil self-sufficing joy illumes the poet’s thought.

This, at least, you teach me,

In a revelation:

That Gods still snatch, as worthy death, the Soul in its aspiration.

And I think, as you thought,

Poesy and Truth ought

Never to lie silent in the Singer’s heart on earth;

Tho’ they be discarded,

Slighted, unrewarded,—

Tho’, unto vulgar seeming, they appear of little worth,—

Yet tender brother-singers,

Young or yet unborn to us,

May seek there, for the Singer’s sake, that love which sweeteneth scorn to us!

While I sit in silence,

Comes from mile on mile hence,

From English Keats’s Roman grave, a voice that lightens toil;

Think you, no fond creatures

Draw comfort from the features

Of Chatterton, that Phäethon pale, struck down to sunless soil?

Scorch’d with sunlight lying,

Eyes of sunlight hollow,

But, see! upon the lips a gleam of the chrism of Apollo!

Noble thought produces

Noble ends and uses,

Noble hopes are part of Hope wherever she may be,

Noble thought enhances

Life and all its chances,

And noble self is noble song,—all this I learn from thee!

And I learn, moreover,

’Mid the City’s strife too,

That such faint song as sweetens Death can sweeten the Singer’s life too!

Lo, thy Book!—I hold it

In weary hands, and fold it

Unto my heart, if only as a token I aspire;

And, by Song’s assistance,

Unto your dim distance,

My Soul upwafted is on wings, and beckon’d higher, nigher.

By the sweeter wisdom

You retain unspeaking,

Though endless, hopeless, be the search, we exalt our Souls in seeking.

Higher, yet, and higher,

Ever nigher, ever nigher,

To glory we conceive not yet, let us still strive and strain!—

The agonizëd yearning,

The imploring and the burning,

Grown awfuller, intenser, at each vista we attain;

And clearer, brighter, growing,

By heavenly waters wander,

Higher, higher yet, and higher, to the Mystery we ponder;

Up! higher yet, and higher,

Ever nigher, ever nigher,

Thro’ voids that Milton and the rest beat still with seraph-wings;

Out thro’ the dark Gate creeping

Where God hath put his sleeping—

A dewy cloud detaining not the Soul that soars and sings,

Up! higher yet, and higher,

Fainting nor retreating,

Beyond the sun, beyond the stars, to the far bright realm of meeting!

O Mystery! O Passion!

To sit on earth, and fashion

What floods of music and of light may fill that fancied place!

To think, the least that singeth,

Aspireth and upspringeth,

May weep glad tears on Keats’s breast and look in Shakspeare’s face!

When human power and failure

Are equalised for ever,

And the one great Light that haloes all is the passionate bright endeavour!

. . . But ah! that pale Moon roaming

Thro’ the gray mists of gloaming,

Furrowing with pearl-bright edge the jewel-powder’d sky!

And ah! the days departed

With friendships gentle-hearted,

And ah! the dream we dreamt that night, together, you and I!

Is it fashion’d wisely,

To help us or to blind us,

At every height we gain, we turn, and behold our Heaven—behind us?

[Notes:

This version of ‘To David In Heaven’ was included in the 1882 Selected Poems, with the following alterations:

v. 1, l. 6: And on the Bridge, in silence, looking upwards, you and I!

v. 1, l. 7: ’Tis the pleasant season ]

___

‘VI. In London, March 1866’ - originally published in The Argosy, April, 1866. ‘In London, March 1866’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works.and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘VII. A Lark’s Flight’ - originally published in The Spectator, August, 1868 (available here), ‘A Lark’s Flight’ was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version (with a few alterations) was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works.and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘De Berny’ - although this was its first appearance in book form, ‘De Berny’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works.and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘The Wake Of Tim O’Hara’ - originally published in All The Year Round, 17 July, 1869. ‘The Wake Of Tim O’Hara’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works.and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘The Northern Wooing’ - from North Coast and Other Poems, 1867. The poem was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version of ‘The Northern Wooing’ was then published in the Chatto & Windus 1884 edition of the Poetical Works.

‘An English Eclogue’ - from North Coast and Other Poems, 1867. The poem was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version of ‘An English Eclogue’ was then published in the Chatto & Windus 1884 edition of the Poetical Works.

‘A Scottish Eclogue’ - from North Coast and Other Poems, 1867. The poem was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version of ‘A Scottish Eclogue’ was then published in the Chatto & Windus 1884 edition of the Poetical Works.

‘Kitty Kemble’ - there is a letter from Buchanan to Alexander Strahan of 1st February, 1873, enclosing a copy of ‘Kitty Kemble’ for publication in The Saint Paul’s Magazine. For some reason it did not appear in the magazine and its first publication seems to be in the 1874 Poetical Works. ‘Kitty Kemble’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

‘L’Envoi To Vol. I.’- This appeared in the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works as ‘L’Envoi To London Poems’ and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site.

__________

The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan

(3 vols. London: Henry S. King & Co., 1874. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co., 1874.)

Vol. II.

BALLADS AND POEMS OF LIFE

LYRICAL POEMS &c.

|