ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{The Fleshly School of Poetry and Other Phenomena of the Day 1872}

56 “THE HOUSE OF LIFE,” &c., RE-EXAMINED.

I HAD written thus far of Mr. Rossetti’s poems, just after reading them for the first time when cruising among the Western Isles of Scotland in the summer of 1871, and I had published my criticism in the Contemporary Review for October (under circumstances explained in my preface), when Mr. Rossetti, goaded into a sense of grievance by the ill-advised sympathy of his friend the editor of the Athenæum, “replied” to the audacious critic who, not being honoured by his personal acquaintance, dared to accuse him of poetic incompetence and literary immorality. Mr. Rossetti’s letter, forming a whole page and a quarter of his favourite weekly print, now lies before me; and I am bound in honour to consider it in some detail. _____ * “Here a critical organ, professedly adopting the principle of open signature, would seem, in reality, to assert (by silent practice, however, not by enunciation,) that if the anonymous in criticism was—as itself originally inculcated—but an early caterpillar stage, the nominate too is found to be no better than a homely transitional chrysalis, and that the ultimate butterfly form for a critic who likes to sport in sunlight and yet to elude the grasp, is after all the pseudonymous.” Surely human ingenuity never so tortured itself to clothe a simple meaning in cumbrous and affected words! The only parallel is the author’s poetry, where a simple kiss becomes a “consonant interlude,” and the ink in a love-letter is called “the smooth black stream that makes thy (the letter’s) whiteness fair!” _____ 57 his letter) I will quote his very words, only italicising them in certain places:— “The primary accusation, on which this writer grounds all the rest, seems to be that others and myself ‘extol fleshliness as the distinct and supreme end of poetic and pictorial art; aver that poetic expression is greater than poetic thought; and, by inference, that the body is greater than the soul, and sound superior to sense.’ As my own writings are alone formally dealt with in the article, I shall confine my answer to myself; and this must first take unavoidably the form of a challenge to prove so broad a statement. It is true, some fragmentary pretence at proof is put in here and there throughout the attack, and thus far an opportunity is given of contesting the assertion. LOVE-SWEETNESS. Sweet dimness of her loosened hair's downfall 58 “Any reader may bring any artistic charge he pleases against the above sonnet; but one charge it would be impossible to maintain against the writer of the series in which it occurs, and that is, the wish on his part to assert that the body is greater than the soul. For here all the passionate and just delights of the body are declared—somewhat figuratively, it is true, but unmistakably—to be as naught if not ennobled by the concurrence of the soul at all times. (!)* Moreover, nearly one half of this series of sonnets has nothing to do with love, but treats of quite other life- influences.I would defy any one to couple with fair quotation of Sonnets 29, 30, 31, 39, 40, 41, 43, or others, the slander that their author was not impressed, like all other thinking men, with the responsibilities and higher mysteries of life; while Sonnets 35, 36, and 37, entitled ‘The Choice,’ sum up the general view taken in a manner only to be evaded by conscious insincerity. Thus much for ‘The House of Life,’ of which the Sonnet ‘Nuptial Sleep’ is one stanza, embodying, for its small constituent share, a beauty of natural universal function, only to be reprobated in art if dwelt on (as I have shown that it is not here) to the exclusion of those other highest things of which it is the harmonious concomitant.”† Thus far Mr. Rossetti; and although it is rather hard to have to refer again to poems so unsavoury, I have no option but to accept the challenge, and judge Mr. Rossetti by “The House of Life” as an uncompleted whole. A reference to this poem, so far from changing my opinion, makes me wonder at the writer’s misconception of its true character. It is flooded with sensualism from the first line to the last; it is a very hotbed of nasty phrases; but its nastiness—or its unwholesomeness—goes far deeper than any phraseology. It opens with a sonnet entitled “Bridal Love,” wherein we are told that “Love,” “Born with her life, creature of poignant thirst _____ * My complaint precisely is, that Mr. Rossetti’s “soul” concurs a vast deal too easily, _____ 59 is preparing “with his warm hands our couch;” and so intense grows the poet’s enthusiasm at this information that he exclaims, wildly addressing his lady in Sonnet II.,— “O thou who at Love’s hour ecstatically —which is a pretty good beginning, quite apart from the blasphemy, for a writer in whose eyes a “beauty of natural universal function” is merely a “harmonious concomitant” of higher things. Sonnet III., entitled “Love’s Light,” describes harmlessly enough how, “—in the dark hours (we two alone) but in Sonnet IV, another and higher stage is reached, for the lady gives her lover a “consonant interlude” (which is the Fleshly for “kiss”), and—“somewhat figuratively, it is true, but unmistakably”—proceeds, as a mother suckles a baby, to afford him full fruition:— “I was a child beneath her touch (!),—a man O malignant critic, who has dared to attaint the author of these sweet lines of “fleshliness!” Let the reader examine this passage phrase by phrase and word by word, dwelling particularly on the descriptive animalism of the last three lines. Why, much the same charge might be brought against that delicious effort of Thomas Carew, entitled “The Rapture,” 60 wherein (quite after the modern fleshly style) the whole business of love is chronicled in sublime and daring metaphor:— “Then will I visit with a wandering kiss Sonnet V. is our favourite already quoted, “Nuptial Sleep,” and Sonnet VI., or “Supreme Surrender,” tells us how— “To all the spirits of love that wander by, There is also this dainty touch about her hand:— “First touched, the hand now warm around my neck Sonnet VII., “Love’s Lovers,” is meaningless, but in the best manner of Carew and Dr. Donne; and the same may be said of Sonnet VIII., “Passion and Worship.” Sonnet IX., “The Portrait,” is a good sonnet and good poetry, despite the epithets of “mouth’s mould” and “long lithe throat.” Sonnet X., the “Love Letter,” is fleshly and affected, but stops short of nastiness. Sonnet XI. is also innocuous. Sonnets XII, to XX. are one profuse sweat of animalism, containing, amongst other gems, this euphuistic description of a kissing match:— Her mouth’s culled sweetness by thy kisses shed _____ * For a production quite in our modern manner, the reader had better refer to this extraordinary poem. I dare not quote another word. _____ 61 and scores of the author’s pet phrases, the veriest pimples on the surface of style, like “wanton flowers,” “murmuring sighs memorial,” “sweet confederate music favourable,” “hours eventual,” “Love’s philtred euphrasy,” “culminant changes”—all familiar enough to us from the Della Cruscans; but culminating, in Sonnet XX., with an image in which the Euphuist would have rejoiced:— “Her set gaze gathered, thirstier than of late, (!) In Sonnet XXI., called “Parted Love,” the lady has retired to get breath and arrange her clothes, and the lover is despairingly waiting from “the stark noon-height” to the “sunset’s desolate disarray.” Sonnets XXII. and XXIII. are too vague for description, but Landor would have stared to see his famous sea-shell image (which he accused Wordsworth of stealing) turned by the euphuistic-fleshly person into “The speech-bound sea-shell’s low importunate strain.” The next four sonnets, called by the affected title of “Willow-wood,” contain, besides the gem about “bubbling of brimming kisses,” some fresh variations of a kiss:— “Fast together, alive from the abyss, An “implacable” kiss! Also:— '”So when the song died did the kiss unclose, The supreme silliness and worthlessness of “Willow-wood,” however, could only be shown by quoting the four sonnets 62 entire. Sonnet XXVIII., or “Still-born Love,” will doubtless suggest to Mr. Rossetti’s admirers other similar themes, and we shall speedily have poetry on “Love’s Cross-birth” and “Love’s Anæsthetics.” Sonnets XXIX., XXX., and XXXI., Mr. Rossetti particularly challenges me to impeach; and I may at once admit that they are not nasty, though very, very silly.In Sonnet XXXII., however, we get back to the old imagery:— “Even as the thistledown from pathsides dead Mr. Rossetti is never so great as on “kisses” and “beds.” In spite of euphuisms without end, we get nothing very spicy till we come to Sonnet XXXIX., one of those which Mr. Rossetti calls immaculate. Here, not content with picturing “Vain Virtues” as Virgins writhing in Hell, he describes the Fire as the Bridegroom, and pursues the metaphor to the very pit of beastliness:— “Virgins . . . . whom the fiends compel There are ten sonnets to come, but must I quote from them? Surely I have quoted already ad nauseam. After the sonnets comes “Love-Lily,” which I have already given in full; then “First Love Remembered;” then “Plighted Promise,” a lyric which I am bound to copy, as it has never been equalled since the famous “Fluttering fold thy feeble pinions” of the “Rejected Addresses:”— 63 “PLIGHTED PROMISE. “In a soft-complexioned sky “Where the inmost leaf is stirred “Have you seen, at heaven’s mid-height, A “soft-complexioned sky!” the “heart-beat of the grove!” “Aurora, Cupid, Dian!” I rub my eyes, wondering if this can be the nineteenth century, till the last lines, with their “bright breast-jewel,” recall me to my subject. But really quotations of this sort become the merest iteration. “The House of Life” contains eight songs more. Four of them, though sensuous in the extreme, have no direct reference to nasty subjects. The other four are sickly love-poems, swarming with affectations. My extracts, however, must close with this verse from the “Song of the Bower” (Mr. Rossetti is great in “bowers”):— “What were my prize, could I enter thy bower, Kindled with love-breath, (the sun’s kiss is colder!) In this and a thousand other passages one thing is apparent: either Mr. Rossetti is stealing wholesale from Mr. Swinburne, or Mr. Swinburne has been all his life robbing Mr. Rossetti. _____ * Compare Greene’s “Menaphon’s Eclogue:”— _____ 65 that, as Mr. Rossetti truly observes, he is driven to frenzy by the real or fancied resemblance between the laugh of the harlot and that of his mistress. “Observe also,” continues the bard, “that these are but seven lines in a poem of five hundred, not one other of which could be classed with them.” Observe, I say in turn, that the whole poem is morbid and unwholesome, and must be drunk in as a whole to leave its full bad flavour. It positively reeks of murder, madness, and morbid lust, and whatever merit it possesses lies in the intensity of its ugly thoughts, from the first moment when the Italian began his courtship in this extraordinary fashion— “What I knew I told —till, blinded with lustful rage, he confesses having murdered her, and tells his dreams:— “She wrung her hair out in my dream In justice we should observe that a madman is speaking; but this madman has Mr. Rossetti’s gift, for here is the sort of conceit with which he delights the priest:— “She had a mouth With the Della Cruscan, the attempt to seem subtle and striking becomes a positive mania. What would be said of a poet who wrote thus?— Her nose inclined to heaven, 66 Yet the one metaphor is every whit as sensible and brilliant as the other. “Bring thou close thine head till it glisten Once more,—conjugal bliss of Adam and Lilith:— “What great joys had Adam and Lilith! The result (next verse):— “What bright babes had Lilith and Adam? All this is savoury, and the whole poem is still more so; so _____ * Compare Carew:— “Now in more subtle wreaths I will entwine _____ 67 that the reader feels a horrible sense of sliminess, as if he were handling a yellow serpent or a conger eel. Let me try blindfold once more for another “draw.” This time my prize is from “Troy Town;” but, before I quote, let me once more premise that the poem as a whole is fleshlier and sillier than any extract. Helen’s breasts, described by herself:— “Each twin breast is an apple sweet! So that Paris, poor fellow, has a fair prospect of being suckled by Helen, and is likely, after “tasting” her “apples” or “breasts meet for his mouth,” to “waste” them (whatever that means) “to his heart’s desire.” _____

PEARLS FROM THE AMATORY POETS. “Belial came last, than whom a spirit more lewd

I HAVE thus carefully gone through Mr. Rossetti’s poetry, not because it is by any means the best or worst verse of its kind, but because, being avowedly “mature,” and having had the benefit of many years’ revision, it is perhaps more 70 truly representative of its class than the grosser verse of Mr. Swinburne, or the more careless and fluent verse of Mr. Morris. The main charge I bring against poetry of this kind is its sickliness and effeminacy; but if there be any truth in my own Theory of Literary Morality, as enunciated some years ago in the Fortnightly Review, the charge of indecency need not be pressed at all, as it is settled by the fact of artistic and poetic incompetence. The morality of any book is determinable by its value as literature—immoral writing proceeding primarily from insincerity of vision, and therefore being betokened by all those signs which enable us to ascertain the value of art as art. In the present case the matter is ludicrously simple; for we perceive that the silliness and the insincerity come, not by nature, but at second hand; Mr. Rossetti and Mr. Swinburne being the merest echoes—strikingly original in this—that they merely echo what is vile, while other imitators reproduce what is admirable. I am loath in this connection to incriminate Mr. Morris. That gentleman is so prolific, so fertile in resources, and is generally so innocent (despite the ever-present undertone of fleshliness), that he may fairly be left to his laurels. He is open to the same literary criticism as the others, but, while often ingenuous, is never altogether unclean. _____ * See Notes. _____ 72 favour, any clever young fellow from a university can force them. And it thus happens that the Fleshly School, without ever reaching the general public, is in favour with the literary amateurs who yearly swarm from college, and ruin the profession of literature by writing anywhere and everywhere free of charge. “Nothing yet in thee is seen; which the reader may advantageously compare with Mr. Rossetti’s description of a love-letter in p. 198 of his volume. The master above quoted, in his “Davideis,” has the following awful passage:— “The sun himself started with sudden fright, This is performing a miracle certainly, but Mr. Rossetti performs a greater—he makes the “Silence” speak:— “But therewithal the tremulous Silence said: Thus sings, or screams, Mr. Swinburne:— “Ah, that my lips were tuneless lips, but pressed Dr. Donne, however, had anticipated him in the same vein:— “As the sweet sweat of roses in a still, These poets ever delight in the strangest and most far-fetched comparisons. Cleveland has a magnificent comparison of the sun to a coal-pit; but Rossetti, twenty times more cunning and subtle, sees that “vows” are the merest bricks:— “We strove Cowley compares his heart to a hand-grenado; in a similar spirit, Rossetti compares the Soul to a town, and (bent to hunt the simile to death) tells us that there are by-streets there, and that Hopes go about hunting for adventures at the public-houses!— “So through that soul in restless brotherhood, Dr. John Donne is great on Tears: they are at one time “globes, nay worlds,” containing their “Europe, Asia, and Africa;” and at another they are “wine,” bottled “in crystal vials” for the tipple of lovers. Mr. Rossetti, in a semi-military spirit, thus describes a Moan:— “A moan, the sighing wind’s auxiliary!” 74 Quite in the spirit of Mr. Rossetti’s fleshlier and commoner manner, in which he talks about his lady’s hand teaching “memory to mock desire,” is Cowley’s exquisite meditation, addressed to his mistress:— “Though in thy thoughts scarce any tracts have been This is the way Dr, John Donne writes in the beginning of the seventeenth century:— “Are not thy kisses, then, as filthy, and more, Could anything more closely resemble the horrible manner of Mr. Swinburne’s “Anactoria?” THE TROJAN HORSE. “A mother, I was without mother born, “That horse, within whose populous womb Again, Mr. Rossetti, in Sonnet XXIX., compares LIFE to “a LADY” with whom he wandered from the “haunts of men,” finding “all bowers amiss” (!) till he came to a place 75 “where only woods and waves could hear our kiss,” and who, as an awful result, bare him three children, Love, Song— “Whose hair Nearly as absurd, but less subtle and harassing, is the passage in Drummond’s “Hymn to the Fairest Fair,” wherein we have the following incarnate metaphor of no less shadowy a shape than “Providence!”— “With faces two, like sisters, sweetly fair, Nor must it be hastily concluded that Mr. Rossetti’s “apples meet for the mouth” simile is quite original. Drummond in one passage calls his mistresses’ hearts “Fruits of Paradise, and in another—the following sonnet—comes tremendously close upon the best modern manner, minus the “lipping” and the “munching:”— “Who hath not seen into her saffron bed _____ * It is perhaps needless to remark the utter confusion of metaphor which makes a love-act with Life as Lady precede the birth of Love, &c. The language of this school will not bear a moment’s serious investigation. _____ The sighing rubies of those heavenly lips, 76 I have quoted this poem entire, because it is quite in the modern spirit, and would certainly, if printed in either Mr. Swinburne’s or Mr. Rossetti’s poems, have been considered beautiful; and partly because I should like the reader to compare it with the Swinburnian conception of “Love and Sleep, as known to the moderns:”— “Lying asleep between the strokes of night The reader whom this fascinates had better turn to Dr. Donne’s eighteenth elegy, every line of which might have been written in our generation, wherein the nude female is compared to a Globe for the lover’s exploration, and the whole Voyage is described with a terrific realism of detail and daring strength of metaphor which would fill even Mr. Rossetti with envy and despair. It is, unfortunately, rather too strong to quote, though not a grain more filthy than the above sonnet. Let me turn, by way of disinfectant, to a 77 conceit in the true Della Cruscan style, from Mr. Rossetti’s works. A very shadowy Entity is speaking, in a poem affectedly called “A Superscription:”— “Look in my face: my name is Might-have-been; This passage, although quite in the ancient manner, was perhaps composed on one of those days when Mr. Rossetti goes poaching in Mr. Swinburne’s French “Slough of Uncleanness,” for we find Baudelaire making use of very similar language:— “Trois mille six cents fois par heure, la Seconde Truly, this sort of reading is wearing to the brain! “Mother of the Fair Delight!” he exclaims; and then proceeds with the following jargon:— “Handmaid perfect in God’s sight, The poem improves as it proceeds, but it is fleshly to the 78 last fibre,—quite, in fact, in the spirit of Richard Crashaw’s poem on “The Weeper:”— “What bright soft thing is this? “O ’tis not a tear, “O ’tis a tear, “Such a pearl as this is This is meant reverently, but what shall we say of Mr. Rossetti’s “Love’s Redemption,” in which the act of sexual connection is outrageously and vilely compared to the administering of the sacramental bread and wine?— “O thou, who at Love’s hour ecstatically,” &c. * Compare, also, with Mr. Rossetti’s pseudo-religious poems generally, those passages of Crashaw in which all the language of passion and lust is used to describe purely spiritual and religious sensations:— _____ * See ante, p. 59. _____ “Amorous languishments, luminous trances, 79 “Delicious deaths, soft exhalations This might have been pardonable in a Roman Catholic of Selden’s time, but the echo of it in a “mature” person of the nineteenth century is positively dreadful.* _____ * Hall, in the ninth satire of Book I., took occasion to attack this blending of incongruous ideas and symbols into affected religious verse. “Hence, ye profane!” he cried, “—mell not with holy things, _____ 80 hours,” “Loves” with “gonfalons,” damsels with “citherns,” “soft-complexioned” skies; flowers, fruits, jewels, vases, apple-blossoms, lutes: I see no gleam of nature, not a sign of humanity; I hear only the heated ravings of an affected lover, indecent for the most part, and often blasphemous. I attempt to describe Mr. Swinburne; and lo! the Bacchanal screams, the sterile Dolores sweats, serpents dance, men and women wrench, wriggle, and foam in an endless alliteration (quite in Gascoigne’s manner) of heated and meaningless words, the veriest garbage of Baudelaire flowered over with the epithets of the Della Cruscans. “Nothing is better, I well think, Or this other of Mr. Rossetti:— “In painting her I shrined her face Apart altogether from the meaninglessness, was ever writing so formally slovenly and laboriously limp? I have no time to pile example on example; I leave that task to the reader, who will not have to hunt far or long for some of the worst writing in our language. Of a piece are such expressions as, “O their glance is loftiest dole!” “in grove the gracile Spring trembles;” “her soft body, dainty thin;” “handsome Jenny mine;” “smouldering senses;” “the rustling covert of my soul;” “a little spray of tears;” “culminant changes;”“wasteful warmth of tears;” “the sunset’s desolate disarray;” “watered my heart’s drouth;” “the wind’s wellaway;” “a shaken shadow intolerable;” “that swallow’s soar” (a swallow, by the way, does not soar); “my eyes, wide open, had the run of some ten weeds to rest upon;” and a thousand others, as bad or worse, all to be found in Mr. Rossetti’s small volume; besides the thousands upon thousands to be found in the works of his more fruitful brethren. _____

“Away with love verses, sugared in rhyme—the intrigues, amours of idlers,

IS this London? Is this the year 1872? That peep of blue up yonder resembles the sky, and these figures that pass seem men and women. What evil dream, then, what malignant influence is upon me?Weary of surveying the poetry of the past, and listening to the amatory wails of generations, I walk down the streets, and lo! again harlots stare from the shop-windows, and the great Alhambra posters cover the dead-walls. I go to the theatre which is crowded nightly, and I listen in absolute amaze to the bestialities of Geneviève de Brabant. I walk in the broad day, and a dozen hands offer me indecent prints. I step into a bookseller’s shop, and behold! I am recommended to purchase a reprint of the plays and novels of Mrs. Aphra Behn. I buy a cheap republican newspaper, thinking that there, at least, I shall find some relief, if only in the wildest stump oratory, and I am saluted instead in these words:— “FANNY HILL. Genuine edition, illustrated. Two volumes, 2s. 6d. each. Lovers’ Festival, plates, 3s. 6d.Adventures of a Lady’s Maid, 2s. 6d.Intrigues of a Ballet Girl, 2s. 6d. Aristotle, illustrated, 2s. French Transparent Cards, 1s. the set. Cartes de Visite from life, 1s. List two stamps. London: H. D——, 15, St. M—— R——d, C——ll. Step where I may, the snake Sensualism spits its venom upon me. The deeper I probe the public sore, the more terrible I find its nature. I ask my physician for his experience; he only shakes his head, and dares not utter all he knows. I consult the police; they give me such details of unapproachable crime as fill my soul with horror. Returning home, I meet a friend, who tells me that the Society for the Suppression of Vice has at last stirred itself, and that the Lord Chamberlain, moreover, has interdicted the last foul importation from France.* O for a scourge to whip these money-changers of Vice for ever out of the Temple! _____ * An interdiction which, says the Athenæum, “is the most wanton violation of liberty, and the most unwarrantable interference with Art, that modern times have witnessed!” It is to be hoped, however, that the Lord Chamberlain will not be dispirited by the indignation of Sir Charles Dilke’s journal, which, as the leading organ of the Fleshly School, is as peculiar in its notions of literary decency as Sir Charles himself in his notions of political propriety. _____ 84 Holywell Street, and writing books well worthy of being sold under “sealed covers.” Much of Mr. Swinburne’s grossness has come of the mad aggressiveness of youth, fostered by reading the worst French poets. Nearly all Mr. Rossetti’s effeminacy comes of eternal self-contemplation, of trashy models, of want of response to the needs and the duties of his time. What stuff is this they are putting forward, or suffering their coterie to put forward for them? It is time, they say, that the simple and natural delights of the Body should be sung as holy; it is unbearable, they echo, that purists should object to the record of sane pleasures of sense; it is just, they reiterate, that Passion should have its poetry and the Flesh its vindication.* As if the “simple and natural delights of the body” had not been occupying our poetry ever since the days of the “Confessio Amantis!” As if sane (and for that matter, insane) pleasures of sense had not been the stock- in-trade of nine-tenths of all our poets and poetasters, from Wyatt to Swinburne! As if Passion had been silent until this year of the Lord 1872, and as if, till the advent of a Rossetti, the world had entirely lost sight of the Flesh! The Flesh and the Body have been sung till the Muses are hoarse again. Two-thirds of our poetry is all Body; nine-tenths of our poets are all Flesh. One would think, from this outcry, that the amative faculty was a new organ discovered by some phrenological bard of the period, and never before traced as having any influence on the human race. One would fancy, from some of our modern criticisms, that the only English poets up to this period had been Milton, holy Mr. Herbert, and the author _____ * See, for example, “A Woman’s Estimate of Walt Whitman” addressed by an English Lady to W. M. Rossetti (1870). _____ 85 of the “Christian Year!” One would swear, to hear these Cupids of the new Fleshly Epoch, that English literature had been veritably getting blue-mouldy with too much virtue, and that the Spirit of Imagination had lived in a nunnery, fed on pulse and cold water, since Chaucer’s time, instead of rioting in a lupanar, fed on hot meat and spiced wine, for hundreds upon hundreds of years! _____ * “The French Revolution,” “Les Misérables,” “The Cloister and the Hearth,” Emerson’s first set of Essays, and “The Scarlet Letter”—all these works are “poems” in the noblest sense. _____ 91 in the great scheme of nature, and how much is to be done on earth besides making night and day hideous with sensual shadows and dreams. Yet, after all, I fear there would be evasion even then; for ten to one you would find some Simple Simon of the amatory type, driven to despair by the universal destruction of looking-glasses, filling the family washing-tub with water from the pump, and pining away into a shadow for love of his own image hovering therein! _____ 92

Page 45.—MR. ROSSETTI’S “JENNY.” SINCE the above was written, the Quarterly Review has spoken in very similar language to my own; and I agree with its strictures in every passage, save those which are levelled against Mr. Tennyson. The poet laureate is open to judgment, and is strong enough to bear it; but I hold it to be in all respects lamentable that he has been censured in the same breath as the men who owe to him what little in their writings is good and worthy. The Review speaks thus of “Jenny:”— ‘Yet, Jenny, looking long at you Exactly. So this profound philosopher, whose somewhat particular reflections on the charms of the sleeper have brought him at last face to face with the mystery of evil, coolly remarks:— ‘Come, come, what good in thoughts like this?’ packs some gold in the girl’s hair, and takes his leave. What good indeed? But why in that case, and if Mr. Rossetti had no power to deal otherwise with so painful a theme, could he not have spared us an useless display of affected sentiment and impotent philosophy? ‘Like a rose shut in a book Affectation and obscurity make the application of this difficult enough. It will not, however, escape notice that the simile is radically false, for whereas the point is that the woman’s heart is alive in the midst of corruption, the rose in the book, to which the heart is compared, is dried and dead.” _____ 94 Page 71.—COTERIE GLORY. That the system by which the school of verse-writers under criticism has made itself notorious is at last defeating itself, is evident from a recent article, entitled “Coterie Glory,” in the Saturday Review—a journal which, I believe, has been more than once made use of by the friends of the gentlemen in question. The author of “Coterie Glory,” in a number of decisive and perfectly well-tempered remarks, surveys the whole question, and on coming to the Fleshly School, openly admits, as if on certain knowledge, that the personal friends of the poets write all the reviews. This also, observes the reviewer, was the case with the once famous “Della Cruscan School,” surviving now only, if it can be called survival, in Gifford’s ponderous but effective satire. 96 These remarks are worth attention, firstly, for their inherent truth; and secondly, because they come from a quarter which can certainly not be accused of friendliness to myself. _____

Page 87.—WALT WHITMAN. There is at the present moment living in America a great ideal prophet, who is imagined by many men on both sides of the Atlantic to be one of the sanest and grandest figures to be found in literature, and whose books, it is believed, though now despised, may one day be esteemed as an especial glory of this generation. It is no part of my present business to eulogize Walt Whitman, or to protest against the popular misconceptions concerning him; but it just happens that I have been asked, honestly enough, how it is that I despise so much the Fleshly School of Poetry in England and admire so much the poetry which is widely considered unclean and animal in America? It is urged, moreover, that Mr. Rossetti and Mr. Swinburne merely repeat the immodesties of the author of “Leaves of Grass,” and that to be quite consistent I must condemn all alike. Very true, if Whitman be a poet of this complexion, if his poetry be shot through and through with animalism as certain stuffs are shot through and through with silk. But it requires no great subtlety of'sight to perceive the difference between these men. To begin with, there are Singers, imitative and shallow; while that other is a Bard, outrageously original and creative in the form and substance of his so-called verse. In the next place, Whitman is in the highest sense a spiritual person; every word he utters is symbolic: he is a colossal mystic; but in all his great work, the theme of which is spiritual purity and health, there are not more than fifty lines of a thoroughly indecent kind, and these fifty lines are embedded in passages in the noblest sense antagonistic to mere lust and indulgence. No one regrets the writing and printing of these fifty lines more than I do. They are totally unnecessary, and silly in the highest degree—silly as some of Shakspere’s dirt is silly—silly in the way of Aristophanes, Rabelais, Victor Hugo—from sheer excess of aggressive life.Fifty lines, observe, out of a book nearly as big as the Bible; lines utterly stupid, and unpardonable in themselves; but to be forgiven, doubtless, for the sake of the spotless love and chastity surrounding them. It is Whitman’s business to chronicle all human sensations in the person of the “Cosmical Man,” or typical Ego; and when he comes to the sexual instincts, he tries to blend emotion and physiology together, to the utter destruction of all natural 97 effect. Judging from the internal evidence of these passages, I should say that Whitman was by no means a man of strong animal passions. There is a frightful violence in his expressions, which an epicure in lust would have avoided.This part of his book, I guess, cost him a good deal of trouble; it is not written con amore; and, apart from its double or mystic meaning, is just what an old philosopher might write if he were trying to represent passion by the dim light of memory. At all events, here Whitman is talking nonsense, as is the way of all wise men at some unfortunate moment or other.Elsewhere, he is perhaps the most mystic and least fleshly person that ever wrote.

________________________________________ VIRTUE AND CO., PRINTERS, CITY ROAD, LONDON. |

|

|

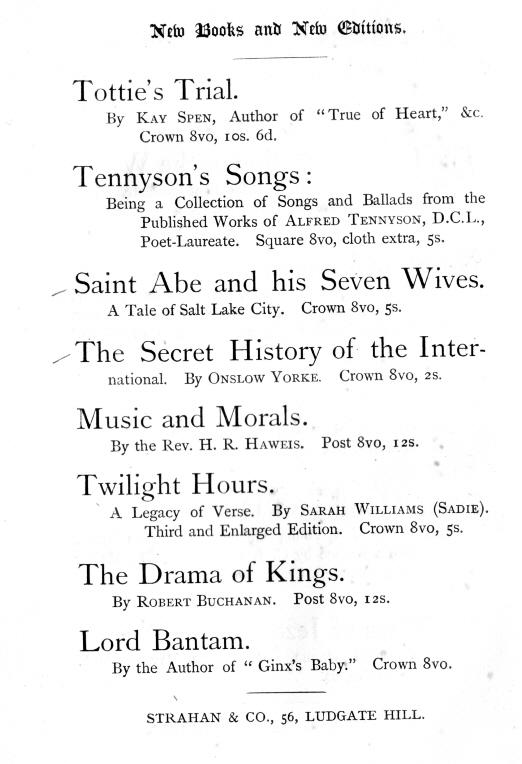

[Second page of the advertisements for “New Books and New Editions - Just Published” featuring Buchanan’s The Drama of Kings and the anonymous Saint Abe and his Seven Wives.] _____

Back to The Fleshly School of Poetry and Other Phenomena of the Day - Contents or Essays or The Fleshly School Controversy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|