ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LETTERS TO THE PRESS (18)

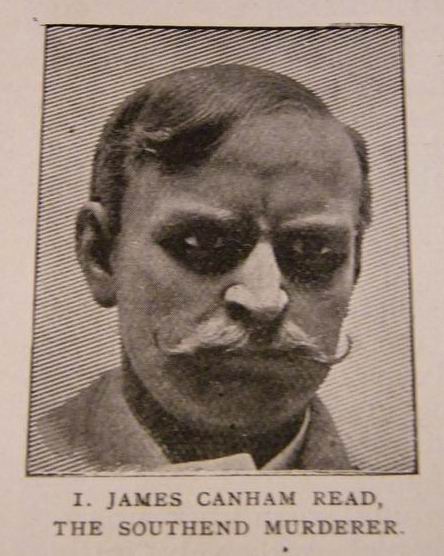

[On the evening of Monday, 25th June, 1894, the body of Florence Dennis, aged 23, was discovered in a brook near the village of Prittlewell. She had died from a single bullet wound to the head. Miss Dennis was eight months pregnant and had been staying with her sister, Mrs. Ayriss, in Southend and on her sister’s evidence at the inquest, James Canham Read, a married man who had had a relationship with Miss Dennis, was arrested for the murder. As well as Read’s home in Stepney where he had a wife and several children (accounts varied from four to eight), he also rented another house in Mitcham, under the name Mr. Benson, where he was living with another woman, Miss Kempton, with their young child. In the course of the trial it was revealed that he had also had a relationship with Mrs. Ayriss and was probably the father of one of her children. Read was not a very sympathetic character but maintained throughout the trial that he was innocent of the crime. He was convicted on purely circumstantial evidence and was executed on 4th December, 1894. Buchanan’s letter was published in The Daily Chronicle and was also copied in full in The Essex County Standard, West Suffolk Gazette and Eastern Counties’ Advertiser and The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post. I feel it should also be noted that Buchanan wrote the letter at the end of November, 1894 - the day before he was due back in the Bankruptcy Court and a little over three weeks since his mother’s death. The newspapers, both national and provincial, followed the story of James Read avidly, and for the sake of adding some background to the case I have placed the accounts of the trial from The Essex County Standard and Reynolds’s Newspaper below.] |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Pall Mall Gazette (16 November, 1894) There rests not a shadow of doubt upon the verdict which the jury found in the Southend murder case. Not one circumstantial link was missing in the chain connecting the crime with the convict Read. The defence was wild and imaginary; its theory was extravagant and unsupported by a single fact of evidence, and its coincidences were too remarkable to influence judge or jury for a moment. Beyond question James Read murdered Florence Dennis in the most horrible circumstances and in the coldest blood. His reasons for the act were obvious, the outcome of an extremely vicious, cruel life. His career was an infamous career of seduction. He added victim to victim without scruple, and, hardened in the end by his own successful villainies, conceived the idea of ridding himself of the woman who had become a burden to him, in order the better to satisfy his evil passion for another. Rarely is so squalid a case discovered in our courts. To be guilty of such infamy a man must lack even the first elements of humanity. When the girl’s condition claimed his remorseful pity and his aid he could think of nothing better than a bloody butchery. If there was ever a criminal worthy of the rope it is James Canham Read. ___

The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin) (30 November, 1894 - p.4) Mr. Robert Buchanan, alleged poet, appears in the newspapers in two somewhat different capacities. In a characteristic letter to the Daily Chronicle he demands the release of the murderer, James Canham Read, the vilest murderer of modern times, of whose guilt the judge and jury had no shadow of doubt, but whom the cocksure Mr. Buchanan proclaims innocent. In another part of the paper the bankruptcy is announced of Mr. Buchanan—debts £15,000, assets nil. It is estimated that his literary income ran close up to two thousand a year, which makes the bankruptcy the less creditable. One would have fancied that his domestic trouble would have diverted his attention for the time being from the vile murderer Read. But Mr. Buchanan is not like the rest of men. We should be glad to have his creditors’ private opinion on the performance. ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (30 November, 1894 - p.2) THERE are some people in this world who cannot be cowed by adversity. For several months Mr Robert Buchanan, novelist, poet, and general caretaker of public morals, has been under the protecting and watchful eye of the Bankruptcy Court. He has now obtained a discharge on condition that he sets aside one half of his income after £900 a year, until his creditors receive 7s 6d in the pound. Mr Buchanan’s case is not, perhaps, a very exceptional one. He just lived far beyond his income. He speculated, he even indulged in a bet occasionally; but all these matters are quite ordinary accompaniments of bankruptcy. But what singles out Mr Buchanan is the impudent assurance with which he lectures the British public on their lack of morality. If anyone scratches Mr Buchanan he is on his high-horse at once; and if he takes up the cause of a criminal, then everyone who differs from him is at once declared to be utterly destitute of any capacity to understand wrong from right. It will be remembered that over the Maybrick case Mr Buchanan became quite hysterical, abusing judge and jury and a lethargic public in the choicest of Buchananese. Now he has got the Southend murderer on hand. Mr Buchanan, of course, holds that the jury were altogether wrong in returning a verdict of guilty. James Canham Read is, in the eyes of Mr Buchanan, a much injured man. The crime has not been brought home to him, and he declares that if Read is executed “he will have been sacrificed to the Mænads of English morality, not to the stern spirit of Justice which cried ‘a life for a life.’” Hysterical rot of this kind can be repeated too often, and Mr Buchanan is one who has exhausted everybody’s forbearance with his emotional humbug. It is high time that some of Mr Buchanan’s personal friends, if he has any, should undertake the responsibility of telling him that when the British public are desirous of being instructed on questions of morality they will seek a safer guide than Robert Buchanan, poet and novelist. ___

The Essex County Standard (1 December, 1894 - p.3) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN INTERCEDES “ANOTHER VICTIM WHOSE GUILT HAS NOT Mr. Robert Buchanan, the well known poet and writer, has addressed the following letter to the Press, dated Nov. 28:—I have waited silently from day to day in the hope that some more authoritative voice than mine might be raised in protest against the judicial murder which will take place, unless the royal prerogative is exercised, on Tuesday next. To my surprise and sorrow, the leading newspapers are still silent concerning the sentence of death pronounced on James Canham Read, the reputed murderer of Florence Dennis. I say the “reputed” murderer, because in my opinion, and in that of many thinking men, the Crown failed utterly to establish its case against the prisoner. Every one who has followed the case for himself, or who has read the admirable letter of “An ex-Chief of Police” in a contemporary, must admit that the chain of so-called circumstantial evidence was imperfect in many of its links. If the life of a human being is to be taken on such evidence as that, no English citizen is safe, and the hideous and barbaric system of judicial murder, which is already the despair of those who work for human civilization, will have secured for itself another victim whose guilt has not been proved. IMMORALITY NOT A CAPITAL OFFENCE. In such a case as the present, in every case which involves the exaction of the extreme penalty, it is infinitely better that a guilty man should escape scot-free than that an innocent man should die upon the gallows. I am quite aware that the popular feeling, at least in London, runs strongly against Read, on the score that he is a man of immoral life; but until we execute men for being immoral (as in God’s good time we may yet do if English Calvinism obtrudes on legislation at its present rate) it is well to reflect that a man of immoral life is not of necessity a murderer, or a man capable of murder. Much of the animus against the condemned man, however, is based upon the assumption that he betrayed and deserted Florence Dennis, even if he did not take her life; yet beyond the statements of the perjured witness, Mrs. Ayriss, there is no proof, whatever, that he was in the company of the murdered girl on one solitary occasion during the eighteen months which followed their first acquaintance, and ended in her death. The Crown was utterly unable to prove a single meeting during that period, and in the solitary written communication between them, Florence Dennis addressed her supposed lover as “Dear sir,” surely a not very probable kind of address from a seduced girl to her betrayer. “ARGUING IN A CIRCLE.” At a first glance, Read’s own failure to account for his time on the day of the murder seems to furnish a certain negative proof against him. It is urged on his behalf that he cannot and will not do so because the so doing would involve the honour, perhaps the life, of another woman. Would a man like Read, it is asked with derision, be so chivalric? But here, again, those who clamour for Read’s life are arguing in a circle, for their chief argument to prove that Read is phenomenally immoral is based upon the assumption that he seduced Florence Dennis, an assumption of which, as I have pointed out, there is no legal proof whatever. Here, as everywhere, the Crown failed to prove his guilt. “ULTRA-PURITANS CRYING FOR BLOOD.” It is fortunate perhaps for humanity that we possess now, at the head of the Home Office, a Minister who, unlike his immediate predecessor, is not afraid to temper justice with mercy, and who is not likely to be carried away by the fevered and prejudiced clamour of ultra-Puritans who cry for blood. If James Canham Read is executed on Tuesday next, he will have been sacrificed to the Mænads of English morality, not to the stern spirit of Justice which cries “a life for a life.” I repeat again, and I refer to the whole case again for my corroboration, that this man’s guilt has not been proved. [The rest of that day’s article on ‘The Southend Murder’ is available here.] ___

The Essex Newsman (1 December, 1894 - p.2) |

|

|

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (1 December, 1894 - p.2) AN OLD CRY REVIVED. JAMES CANHAM READ lies under sentence of death for the murder of Florence Dennis, and unless the Royal prerogative be exercised the wretched man will bid the world farewell on Tuesday next. If ever man deserved such fate surely that man is Read. His notoriously immoral life does not enter into calculations; only his cowardly and clod-blooded murder of the girl he had betrayed may be considered. Nothing more is required. A murder so dastardly can be expiated but in one manner. Yet the party of sickly sentimentalism is lifting up its voice in protest against the fulfilment of the sentence; even Read has found supporters who are attempting to argue that the charge was not proven. So long as the agitation was confined to the anonymous correspondents of a journal anxious for a cheap catchpenny boom it was unworthy attention, but when a man of the prominence of Mr. Robert Buchanan comes forward to lend his influence, it is time to protest. The point which Mr. Buchanan and his companions urge is that the guilt of Read has not been proven. The evidence was purely circumstantial, and links of the chain were by the acknowledgment of the prosecution missing; yet, on the whole, as complete a case was presented that the jury had no hesitation in returning the verdict with which Mr. Baron Pollock, a judge of the greatest impartiality, signified his acquiescence. The case against Read was strong; what was his answer? Did he give any information as to his movements on the day of the murder? He has hinted that he was many miles away, but of evidence of the fact he produced not a tittle. It is hinted that he was engaged at the time in yet another of his numerous liaisons, and that rather than reveal the facts and injure the good name borne by some dishonest woman he is prepared to suffer. Read’s conduct does not indicate that pure chivalry would carry him thus far, and what woman, however keenly she would feel the world’s reproaches, would allow her own reputation to outweigh the life of her lover? Besides, supposing Read’s story to be true, the woman would not be the only person with whom he came in contact. Read might if he would indicate his hinted whereabouts on the fatal night without implicating any mistress whom he desired to shield. Yet on the subject he takes refuge in silence—not even to his own brother will he mention the name of the town or village where the alleged mistress resides. Yet in spite of the fact that the evidence against Read is so damning, and that Read declines to prove, as he could by a word, the innocence he asserts, the Home Secretary is warned that the execution of the man will be “judicial murder,” and he is petitioned to grant a reprieve. To transform Read’s condemnation to penal servitude for life would be a piece of foolishness of which Mr. Asquith is too clever a man to be guilty. If Read is not deserving of the full penalty he is an innocent man, and ought not to be kept in prison another hour. If he requires punishment in connection with the murder of Florence Dennis only one punishment is possible. If the Home Secretary, after the perusal of the evidence, comes to the opinion that Read is innocent he must throw open the doors of the gaol; if he cannot arrive at that conclusion, he has no ground for interfering with the due course of the law. ___

The Yorkshire Herald (1 December, 1894 - p.5) TUESDAY is fixed for the execution of James Canham Read. An attempt is being made to secure a reprieve, in which Mr. Robert Buchanan has joined, with his usual vehemence of language. We entirely agree with Mr. Buchanan that a man amy be grossly immoral without being capable of murder. But the suggestion that Read is to be hanged because of his immorality is too absurd. The man had a perfectly fair trial before a judge who has never been accused of incapacity or prejudice; he was defended by a most able member of the Bar; and he had every opportunity of producing evidence that he was not near Southend on the night of the murder. No such evidence was, however, forthcoming, and in the absence of it, there is difficulty in seeing how any reasonable person can doubt the guilt of Read. So long as capital punishment is the law of the land it must be enforced; and there is nothing to justify intervention in the case of the murderer of Florence Dennis. ___

The Referee (2 December, 1894 - p.1) [A comment piece about court reporting and the importance of circumstantial evidence.] |

|

|

St. James’s Gazette (3 December, 1894 - p.4-5) The Home Secretary, as might have been expected, has not found any reason for over-ruling the verdict of the jury in the case of the murderer Read; and the wretched man will be hanged to-morrow. Such pertinacious and indomitable sentimentalists as Mrs. Josephine Butler and Mr. Robert Buchanan will probably indulge in one or two more shrieks over another failure to redeem from the gallows a man whose guilt was only proved by circumstantial evidence to the satisfaction of twelve average British males and a particularly clear-headed and fair-minded judge. But Mrs. Josephine Butler and Mr. Robert Buchanan would not do much harm, were it not that certain newspapers give them publicity. Why the Prison Commissioners or the visiting justices allow such sensational “copy” as a convict’s letters to be obtained and placarded about the streets, we do not know. Sir Edmund Du Cane should see to it. But the evil effect of this criminal sensationalism is certain. The prisoner himself is deluded; the law is blasphemed; the law-abiding are scandalized; and a cheap notoriety is held out to the reckless and the vicious. ___

[Two accounts of the execution of James Canham Read which took place on Tuesday, 4th December, 1894.] |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Dover Express (7 December, 1894 - p.6) OUR LONDON LETTER. It is understood that we do not necessarily identify . . . The Home Secretary came to Downing-street on purpose to go thoroughly into the petitions that had been sent in asking for a reprieve for James Canham Read. The failure of the agitators who took up the case to obtain signatures, or to advance a single fact to support the convicted man’s assertions, and the character of the agitation itself, circumscribed as it was, was tantamount to a strengthening of the verdict. For a long while not a hand was raised for the wretched convict at Chelmsford gaol, but one halfpenny evening paper for several days latterly, diligently boomed the subject, and opened its columns to all and any who had arguments to advance. The fatal thing about the correspondence was that nearly all who demanded a reprieve confessed themselves hostile on principle to capital punishment, or were avowedly “cranks” who had something of interest only to themselves to obtrude. The most powerful letter was written by Robert Buchanan. This agitation also induced wonder as to what has become of that Society for the Abolition of Capital Punishment, which at one time had real influence. There is confessedly a strong feeling in the country against the capital penalty—witness, for example, the jury who recently recommended to mercy one who had murdered his wife and son, on the plea that he was a man of low type, but it has little organisation. It is a shocking reflection on our civilisation that on the 2nd December there were eight men under sentence of death in this country. ___

[More information about the case is available at Murderpedia, including this photo of James Canham Read: |

|

|

[Note the funny colour - this is because this bit treads into the realm of wild speculation and is solely due to my fondness for American TV crime shows. When looking in the online newspaper archives I accidentally came across another ‘Southend Murder’, which occurred almost exactly a year before the Read case. On Saturday 20th May, 1893, Emma Hunt (aged 38) was found in a brook near the village of Rochford (which lies two and a half miles north of Prittlewell), with her throat cut. The youth who found the body, Alfred Hazell, was later arrested, but the case never came to court, the charges were dropped and the crime remained unsolved. I found it odd that none of the newspaper accounts of the Read case mentioned this earlier murder and I do think Read’s Q.C. missed a trick by not referring to it in his address to the jury, if only to sow some seeds of doubt in their minds. I’m not suggesting that Read was innocent, or that Jack the Ripper had moved to Southend, I just thought it strange that no one mentioned the similarities with the earlier crime. If your curiosity has been piqued the picture below will take you to a report of the murder from Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (4 June, 1893).] |

|

|

[Another extract from a letter in The Daily Chronicle.]

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (15 March, 1895 - p.2) Mr ROBERT BUCHANAN, the poet and dramatist, has a characteristic letter in the Daily Chronicle on the new play, “The Notorious Mrs Ebbsmith.” . . . “THE NOTORIOUS MRS EBBSMITH.” MR ROBERT BUCHANAN ON THE NEW PLAY. Mr Robert Buchanan, in the course of a long letter to the Daily Chronicle, says:—The great scene of “The Notorious Mrs Ebbsmith” is, I understand, one in which the heroine, after throwing the Bible into the fire, plucks it from the burning and sobs over it hysterically, preparatory to retiring into the odour of sanctity with “a clergyman and his sister.” Is it necessary to say to any one acquainted with life that such a scene is as gross a caricature of Socialism and free thought as Lord Tennyson’s picture of an atheist in the “Promise of May?” No woman brought up as Agnes had been—no woman who knows what freethought and Socialism are—could have been guilty of so gross an absurdity. But that is neither here not there. My contention is that the superficially unconventional play would be approved by Mr Archer and the Kirk-Session, while the really unconventional play would be rejected with horror. Can any reader conceive a scene in which a hero or heroine threw the Bible into the fire while proclaiming the evils which, to his or her thinking, it had caused to humanity? Yet such a scene would be as defensible as—and possibly less absurd—than the other. If we are to have freedom of utterance (which I for one claim) let us have it, I repeat, all along the line. Do not let us be deluded into the belief that the pathological drama, written half-heartedly in defence of formulas approved by the “will of the people,” is any real advance on the old-fashioned drama written for public amusement. If Mr Pinero is to have the right to burlesque freethought and free thinkers (and I for one would certainly give him that right), and to beg the whole social question with a religious platitude, let other men also have the right to treat morality and religion as subjects. This, under the supervision of a Council founded on “the will of the people,” they would never be suffered to do. In a word, art need not be free at all unless it is free altogether. _____ The Times says:—“Like its congener, ‘The Notorious Mrs Ebbsmith’ is a painful but on the whole a deeply absorbing play, which under an unpromising exterior, inculcates the highest morality.” ___

[The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith by Arthur Wing Pinero was revived in 2014 at the Jermyn Street Theatre. There’s a review on The Guardian’s site, and a ‘trailer’ on youtube. The play is also available at the Internet Archive.] __________

[This page was originally in the Miscellanea section since I have not seen copies of Buchanan’s letters to The Star and have used extracts culled (mainly) from two secondary sources: Michael S. Foldy’s The Trials of Oscar Wilde (Yale University Press, 1997) and Jonathan Goodman’s The Oscar Wilde File (Allison & Busby, 1988, pp. 95-99). However, its proper place is here. Following Oscar Wilde’s arrest, Robert Buchanan was one of the very few public figures to speak out on his behalf, and wrote four letters to The Star on the subject. One day I will get round to presenting this page properly, until then, accept my apologies.]

From The Trials of Oscar Wilde by Michael S. Foldy (Yale University Press 1997, page 59.) “What is most important is that although private opinion seems to have been divided as to whether Wilde was courageous or foolhardy to have pursued the case against Queensberry, and then to have refused to flee the country after the failure of his prosecution, public support for Wilde was virtually non-existent. The sad fact of the matter was that at this most crucial moment of his life, Wilde had been abandoned by virtually all his friends. The social stigma attached to the alleged crime was so severe that it would have been unthinkable for anyone to defend Wilde’s lifestyle. To do so would have been to invite the panoptic eye of society to examine one’s own life. Efforts to differentiate between the man and his work seemed equally fruitless, which made it virtually impossible for anybody to speak out publicly on his behalf. Any defense of Wilde would necessarily have been construed as implying a defense of Wilde’s lifestyle. ___

The Star (16 April, 1895) Letter from Robert Buchanan (extract): Sir, Is it not high time that a little charity, Christian or anti-Christian, were imported into this land of Christian shibboleths and formulas? Most sane men listen on in silence while Press and public condemn to eternal punishment and obloquy a supposed criminal who is not yet tried or proved guilty. ... I for one, at any rate, wish to put on record my protest against the cowardice and cruelty of Englishmen towards one who was, until recently, recognised as a legitimate contributor to our amusement, and who is, when all is said and done, a scholar and a man of letters. He may be all that public opinion avers him to be; indeed, he stands convicted already, out of his own mouth, of the utmost recklessness and folly; but let us bear in mind that his case still remains sub judice, that he is not yet legally condemned. Meanwhile, we are asked by the advocates of orthodox sensualism not merely to trample an untried man in the mire, but to expunge from the records of our literature all the writings, which, only yesterday, tickled our humor and beguiled our leisure. ... Even if one granted for a moment that the man was guilty, would that be any reason for condemning work which we know in our hearts to be quite innocent? ... Let us ask ourselves, moreover, who are casting these stones, and whether they are those ‘without sin amongst us’ or those who are themselves notoriously corrupt. Yours etc. ROBERT BUCHANAN. [This extract is a composite from two sources: ‘Buchanan closed his letter with these words, “let us ask ourselves, moreover, who are casting these stones, and whether they are those ‘without sin amongst us,’ or those who are themselves notoriously corrupt.” Interestingly, Buchanan’s closing remarks struck a nerve with Lord Queensberry.’ ] ___

The Star (19 April, 1895) Letter from Lord Queensberry: Sir,—My attention has only to-day been called to Mr. Robert Buchanan’s letter in your issue of Tuesday night. I have received many anonymous letters, and it is vexatious not to be able to reply to some of them. One this morning called my attention to this letter of Mr. Buchanan. Can it possibly have come from himself? or was it inspired by him? I have not the pleasure of Mr. Buchanan’s acquaintance, but he seems to address a question to myself in this letter to your paper of the 16th April when he says, ‘Who are casting these stones? and are they without sin or those who are notoriously corrupt?’ Is Mr. Buchanan himself without sin? I certainly don’t claim to be so myself, though I am compelled to throw the first stone. Whether or not I am justly notoriously corrupt I am willing patiently to wait for the future to decide. Judge not that you be not judged I would add until you were qualified to know all the actual facts of a man’s life and what he really was.—Yours, &c., ___

The Star (20 April, 1895) Letter from Lord Alfred Douglas: SIR,—When the great British public has made up its great British mind to crush any particular unfortunate whom it holds in its power, it generally succeeds in gaining its object, and it is not fond of those who dare to question its power, or its right to do as it wishes. I feel, therefore, that I am taking my life in my hands in daring to raise my voice against the chorus of the pack of those who are now hounding Mr. Oscar Wilde to his ruin; the more so as I feel assured that the public has made up its mind to accept me, as it has accepted everybody and everything connected with this case, at Mr. Carson’s valuation. I, of course, am the undutiful son who, in his arrogance and folly, has kicked against his kind and affectionate father, and who has further aggravated his offence by not running away and hiding his face after the discomfiture of his friend. It is NOT A PLEASANT POSITION to find oneself in with regard to the public, but the situation is not without an element of grim humour, and it is no part of my intention to try and explain my attitude or defend my position. I am simply the “vox in the solitudine clamantis” raising my feeble protest; not in the expectation of making head against the wave of popular or newspaper clamour, but rather dimly hoping to catch the ear and the sympathy of one or two of those strong and fearless men and women who have before now defied the shrieks of the mob. To such as these I appeal to interfere and to stay the hand of “Judge Lynch.” And I submit that Mr. Oscar Wilde has been tried by the newspapers before he has been tried by a jury, that his case has been almost HOPELESSLY PREJUDICED in the eyes of the public from whom the jury who must try his case will be drawn, and that he is practically being delivered over bound to the fury of a cowardly and brutal mob. Sir John Bridge, in refusing bail today, stated that he knew of no graver offence than that with which Mr Wilde is charged. Mr Wilde, as a matter of fact, is charged with a “misdemeanour” punishable by two years’ imprisonment with or without hard labour as a maximum penalty; therefore, the offence with which he is charged is, in the eye of the law, which Sir John Bridge is supposed to represent, comparatively trifling. I should very much like to know how, in view of this fact, Sir John Bridge can reconcile what he said with his conscience, and with his position as the absolutely impartial exponent of the law, and whether it is not obvious that, in saying what he did, he allowed his personal feelings on a particular point to override his sense of abstract justice, to the prejudice of the man charged before him. If a police magistrate of twenty years’ experience shows such flagrant prejudice, what can be expected from the men who will at the Old Bailey form the jury of what the law humorously terms Mr Oscar Wilde’s “peers”? _____

Letter from Robert Buchanan (extract): I am sure that Lord Queensberry, who has himself suffered cruelly from the injustice of public opinion, is quite as sorry as I am for his fallen foe, and is quite as anxious as I am that he should be dealt with fairly, justly, and even mercifully. Personally, I would not condemn even a dog on the kind of tainted evidence which has been foreshadowed during the recent preliminary inquiry, but the case, as I said, is still only sub judice, and none of us yet know with any certainty whether or not a jury of Englishmen will pronounce Mr. Wilde guilty. ASSUME THE GUILT beforehand. Assume for a moment that the prisoner is acquitted, what amends can be made for treatment which is as unjust as it is abominable? As matters stand, we may shatter a man's health, torture his mind and his body, drive him into madness or imbecility, and then, finally, if it turns out we are mistaken, all we can do is say, “We’re very sorry!—we beg your pardon!—you can go!” 19 April ROBERT BUCHANAN ___

The Star (21 April, 1895) SIR,—I chanced to read two letters in your issue of this evening, one from Lord Alfred Douglas and another from Mr. Buchanan, in connection with the proceedings against Wilde in the law courts. London 20 April. COMMON SENSE. (We have received a host of other letters bearing on the Wilde case, which, for various reasons, we have decided not to publish. — Ed. Star.) ___

The Star (22 April, 1895) OSCAR WILDE. TWO VIEWS OF HIS PRESENT POSITION. Has he been Unfairly or Prematurely Judged by Magistrate and Public, or does His Case Illustrate the Need of Prison Reform? TO THE EDITOR OF “THE STAR.” SIR,—After some howls of execration, the expunging of an author’s name from the public playbills, and other acts of Christian charity which have lately been witnessed, it may not be out of place to enter some kind of protest against this very hasty prejudgement of a case still pending. After all, in sexual errors, as in every thing else, the real offence lies, and must always lie, in the sacrificing of another person in any way, for the sake of one’s own pleasure or profit; and judged by this standard—which though not always the legal standard is certainly the only true moral standard—the accused is possibly no worse than those who so freely condemn him. Certainly it is strange that a society which is continually and habitually sacrificing women to the pleasure of men, should be so eager to cast the first stone—except that it seems to be assumed that women are always man’s lawful prey, and any appropriation or sacrifice of them for sex purposes quite pardonable and “natural.”—Yours, &c., HELVELLYN. ___

The Star (23 April, 1895) OSCAR WILDE. MR. BUCHANAN PLEADS FOR And Says That Wilde Has Already Lost Everything That Can Make Life Tolerable—Another Correspondent Holds Different Views of “Christian Charity.” TO THE EDITOR OF “THE STAR.” SIR,—Just one word before you close this discussion, in answer to your correspondent “Common Sense.” What I claim for Mr. Wilde I should certainly claim for any untried prisoner, Mr. William Sikes included; and I certainly do not think that a question of the liberty of the subject should be postponed sine die, on any possible plea of inexpedience. When an outrage on liberty is committed or threatened is the right time to protest against it. 22 April. ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

SIR,—The two letters which you publish to-day appear to be specimens of the opposite views held on the Wilde case. It is a matter for regret that an epistle like that of “Helvellyn” should be produced as the views of anyone. Whitehall, S.W., 22 April. DIKE. (We have received another large batch of letters on this subject, some of them from Liverpool, Middlesbrough, and other far-off centres, but none expresses views different from those which have been published from other correspondents.) ___

The Star (24 April, 1895) Letter from Robert Buchanan (extracts): ... Has even a writer like this no sense of humour? Does he seriously contend that the paradoxes and absurdities with which Mr. Wilde once amused us were meant as serious attacks on public morality? Two thirds of all Mr. Wilde has written is purely ironical, and it is only because they are now told that the writer is a wicked man that people begin to consider his writings wicked. ... I think, I am as well acquainted as most people with Mr. Wilde’s works, and I fearlessly assert that they are, for the most part, as innocent as a naked baby. As for the much misunderstood “Dorian Gray,” it would be easy to show that it is a work of the highest morality, since its whole purpose is to point out the effect of selfish indulgence and sensuality in destroying the character of a beautiful human soul. But it is useless to discuss these questions with people who are colour-blind. I cordially echo the cry that, failing a little knowledge of literature, a little Christian charity is sorely wanted. ... ... While we have a whole mob of savages clamoring ... for lynch-law and retribution, we have not one Christian clergyman to utter a sound. Be the victim either Jean Valjean or Oscar Wilde, “Bill Sikes” or the Marquess of Queensberry, no Bishop Miguel appears (save in romantic fiction), to preach and to practise forgiveness. That, I may add, is left to the “agnostic,” who has most right to feel revengeful. I heard from the Marquess of Queensberry’s own lips that he would gladly, were it possible, set the public eye an example of sympathy and magnanimity.—Yours, &c., 23 April. ROBERT BUCHANAN

[The first extract from this letter appeared in Oscar Wilde: Art and Morality A Defence of “The Picture of Dorian Gray” Editor: Stuart Mason (London: J. Jacobs, 1908) available at the Internet Archive. The book is also available as a LibriVox recording and the relevant section, ‘Mr. Robert Buchanan on Pagan Viciousness’ can be heard here. “On the same day that a notice announced the sale of Wilde’s possessions in order to help with expenses relating to the trial, Buchanan responded vigorously to DIKE’s “lying perversions of truth.” After characterizing DIKE as an “anonymous coward” and someone who “snaps and gnaws at a fallen man,” Buchanan addressed himself to “the only serious statement in ‘DIKE’s’ letter,” which interpreted Wilde’s abandonment of his prosecution of Queensberry as an admission of guilt. Buchanan argued that by withdrawing in the face of “unexpected evidence” Wilde had only done what was prudent and reasonable, and that DIKE had jumped to conclusions based on evidence whose precise contents and sources had yet to be examined and understood. He further defended Wilde by saying that “two thirds of all Mr. Wilde has written is purely ironical, and it is only because they are now told that the writer is a wicked man that people begin to consider his writings wicked [also].” — From The Trials of Oscar Wilde by Michael S. Foldy, p. 64).] ___

The Star (25 April, 1895) TO THE EDITOR OF “THE STAR.” SIR,—I must take exception to the word “sympathy” that is placed in my mouth. I never used it. In my time I have helped to cut up and destroy sharks. I had no sympathy for them, but may have felt sorry, and wished to put them out of pain as soon as possible. 24 April. QUEENSBERRY. ___

Dundee Advertiser (27 May, 1895 - p.5) At the first blush most people will incline to think the sentence on OSCAR WILDE a cruel one. Two years’ imprisonment with hard labour mean more to him than to a misdemeanant of inferior powers and obscure station. WILDE has already fallen under a severity of public condemnation almost immeasurable and, happily, such as comes to few men in a century; his status and his opportunities are destroyed; the very gifts which carried him into the first rank of British writers are doomed to waste. But, on reflection, we believe the sentence to be wholly just and wise. The publicity given to ideas and practices dangerous to social health renders it necessary that WILDE’S offence should be stamped with all the censure that the law allows. WILDE’S unpardonable sin is that, with great powers of mind and a judgment fitted to discern what made for good and what for evil, he has acted as a deliberate corrupter of youth. He has poisoned the atmosphere about him. Apart from this, WILDE has simply to be taken as a sexual pervert of a type familiar enough to students of the pathology of disease; and his immense egotism is but another symptom of a nature off the normal line. Were it not for the social consequences of his conduct and the necessity for a penalty calculated to arrest these, the asylum would be a fitter place for him than the prison. The amazing thing is that so great a virility of intellect should have existed in a nature otherwise capable of living below the plane of sanity. The key to the enigma lies in some obscure recess of the brain as yet unvisited even by the scientific specialist. The whole subject is loathly, and the wholesome mind forced to dwell upon it, if but for a moment, calls for open windows and the fresh air. For the public good nothing is so much to be desired than that a sudden and complete oblivion should fall upon this repulsive case. It is a duty to refrain even from private whispers of WILDE’S name, so that there may be no further spreading of the contagion of evil. For the like reason we trust the pulpit and press will restrain their tendency to ill-considered homilies against such facile dogmas as “art for art’s sake.” This is not the time to discuss the true relation of art to morals, and hasty deliverances called forth by the revelations in Court of a diseased organism will assuredly provoke defences of the half-truths the attacked dogmas cover. There is hardly one of WILDE’S paradoxes but could be justified in some sort by a sane mind and a normally moral nature, and, to tell the truth, there are few sane minds and moral natures but would be proud to call nine-tenths of WILDE’S printed writings their own. Again the enigma—so much brilliance, so much bestiality! Do not let us, therefore, have immature attempts to connect WILDE’S revolting conduct with his critical opinions or to extract lessons therefrom. When an animal with lustful eyes and gross desires shows itself in a nature that might otherwise have been great, we do not study the animal in the market-place—we shut it away. _____

Robert Buchanan and Oscar Wilde - an additional note

Buchanan’s defence of Wilde is not mentioned in Harriett Jay’s biography and I always wondered whether Oscar Wilde acknowledged Buchanan’s support in any way. When the archives of The Guardian newspaper went online in November 2007 I came across the following item:

The Guardian (27 June, 1929 - p.10) The Modern First-Edition Craze. The prices paid at Sotheby’s to-day for first editions of Shaw, Hardy, Barrie, Wilde, and one or two other modern authors will make many more of us think of having our bookshelves “vetted.” It is hard to convince most people who have been buying books off and on for thirty years that they have not some book of value under the new market conditions if they could only spot it. Of course the people who have books with the author’s autograph are likely to know of it, and those are the ones that fetch the top prices. But the ordinary first edition in good condition by about twenty living authors has now high rarity value. The biggest price to-day was £310 paid for a copy of Wilde’s “Salome” inscribed in the handwriting of the author: “George Bernard Shaw, with the author’s compliments. February, 93.” And then presented by Mr. Shaw to “Bertha Newcombe from G. Bernard Shaw, May, 1893.” Another first edition sold by Miss Newcombe was Shaw’s “Widowers’ Houses,” inscribed by the author to the lady in May, 1893. It brought £155, and the “Unsocial Socialist” £142. A first edition of Wilde’s “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” was inscribed by the author to Robert Buchanan, and inserted in it was a letter in Wilde’s handwriting about the officials of Reading Gaol, written in Posilipo in November, 1897. It finishes: “For four days I have had no cigarettes—no money to buy them—or no paper.” This book and letter fetched £170, which would have gone a long way to buy cigarettes and notepaper for Wilde. An email to David Rose of the Oscholars site elicited the information, courtesy of Mark Samuels Lasner of the University of Delaware Library, that Buchanan’s copy of The Ballad of Reading Gaol now resides in the Robert H. Taylor Collection at the Princeton University Library. Thanks are also due to Meg Sherry Rich of the Princeton University Library for confirming this and offering the following information: “It is inscribed to Buchanan by Wilde and dated March ’98. There’s a note penciled in the front, probably by a dealer, about a “very interesting letter about the poem,” but the letter is not laid in or tipped into this volume.” The fact that the letter (mentioned in the Guardian article) has been separated from the book may mean that the letter was not addressed to Buchanan and, perhaps, was passed on to Buchanan by one of Wilde’s friends after the publication of his first letter in the Star (16th April 1895). In his letter of 20th April Buchanan mentions Wilde’s lack of cigarettes, a fact referred to in the quotation from the letter in the Guardian article, and my feeling is that Buchanan could have been given the letter sometime between the 16th and the 20th April. So, when Harriett Jay (presumably) decided to sell the book, she included the letter with it. But this is all speculation, and whatever the origin of the letter, the important thing is that Oscar Wilde did acknowledge Robert Buchanan’s support by sending him a copy of The Ballad of Reading Gaol. This item ended here originally, but a little more light was shed on the matter when, in 2019, I acquired copies of Buchanan’s letters held in the Charles E. Young Research Library of UCLA, among which were several letters to Leonard Smithers, the publisher of The Ballad of Reading Gaol. The first of these, dated 5th March [1898], contains the following: “Will you kindly forward the enclosed letter to Mr Wilde? It is merely a line congratulating him on his reappearance in literary life, at which I am more than pleased, as I was almost solitary among men of letters in trying to procure him justice & fair-play.” The first edition of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, was published, anonymously, on 13th February, 1898. The third edition, published on 4th March was ‘signed by the author’. Whether Buchanan discovered that Wilde was the author at this point and wrote to Smithers, and Wilde responded to the forwarded letter (presumably now lost) with a copy of the book, or whether Wilde had already sent Buchanan a copy, which then prompted Buchanan’s letter to Smithers, I don’t know. _____

Acknowledgements: I first became aware of Robert Buchanan’s public defence of Oscar Wilde during an internet search when I came across the Court Theatre (Chicago) Playnotes on Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde by Moises Kaufman. David Rose then published my appeal for more information about this connection between Buchanan and Wilde in The Oscholars (the online Journal of Wilde Studies) which prompted an email from Angie Kingston of the University of Adelaide whose research for her PhD thesis, “Wilde Imaginations: Oscar Wilde as a Character in Victorian Fiction” had thrown up several connections between Wilde and Buchanan (including the fact that Buchanan had fictionalised Wilde (as ‘Mervyn Darrell’) in his 1894 play “The Charlatan”) and who suggested several books including Jonathan Goodman’s “The Oscar Wilde File”. __________

[When Buchanan’s play, The New Don Quixote was refused a licence by the Lord Chamberlain he wrote a letter to The Observer, which was printed on 15th December, 1895. Extracts from this letter are available below.]

Edinburgh Evening News (16 December, 1895 - p.3) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN AND THE The Observer publishes from Mr Robert Buchanan an indignant remonstrance against the action of the Lord Chamberlain in refusing to license one of his dramas—“New Don Quixote,” a four-act play. He says: “I have no intention of resting quiescent under the imputations of the Lord Chamberlain, and I shall join issue with that functionary in the manner best fitted to justify me in the eyes of the public. Having been chosen as the scapegoat of my class, I accept the position, not altogether without satisfaction; for the time has come, I believe, when one man’s martyrdom may become the salvation of the English drama.” ___

The Glasgow Herald (16 December, 1895 - p.4) MUSIC AND THE DRAMA. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) London, Sunday Night. Mr Robert Buchanan has to-day issued a lengthy protest against the new Examiner of Stage Plays. Mr Buchanan states “The New Don Quixote,” a four-act play, “written by myself and another author,” and accepted by Mr Bouchier for production at the Royalty Theatre, has just been returned to the manager with the intimation that it will not be licensed for representation. Mr Buchanan goes on to say that the Lord Chamberlain will take no official knowledge of authors as such, having, of course, to deal solely with theatrical managers, and that the public know his own views on the subject of censorship. He continues:—“The play in question is, I contend, pure and wholesome, though it deals boldly and seriously with some of the great issues of modern life. Its offence, I presume, consists in this, that it is neither trivial nor indecent in the ordinary sense, but that it is fundamentally and not superficially unconventional.” In accordance with custom in such cases, Mr Buchanan, it is understood, proposes to publish his play, when the public will be able to determine for themselves whether the reader of stage-plays or the author is in the right. ___

The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin) (16 December, 1895 - p.5) That stormy petrel of the drama, Mr. Robert Buchanan, has a new grievance against the Lord Chamberlain. He writes an indignant letter to the papers saying—“May I call your attention to the fact that the ‘New Don Quixote’ a four act play written by myself and another author, and accepted by Mr. Bourchier for production at the Royalty Theatre, has just been returned to the manager with the intimation that it will not be licensed for representation. No reason is assigned for this high-handed measure, and the licenser of plays on being appealed to by me to state the nature of the objections refers me to a clause in the Lord Chamberlain’s circular to the effect that the Lord Chamberlain has no official knowledge of ‘authors as such!’ Thus I am not only left under the stigma of having written a play which is unfit to see the light, but I am unable to ascertain in what respect I and my fellow author have offended!” As may be expected, Mr. Robert Buchanan is not going to lie quietly under the slur cast upon him by the Lord Chamberlain. At the same time it is impossible to see what effectual protest he can make, as there is absolutely no appeal from the decision of that functionary. Judging by his letter, the Lord Chamberlain does not merely take exception to any particular passages or scenes in the play, but refuses to license it on general grounds. Mr. Buchanan can, without the licence of the Lord Chamberlain, get the play produced privately at his own expense, but such a proceeding would be costly, and as far as one can see useless. ___

The Sporting Life (18 December, 1895 - p.6) Mr. Redford, the present “Examiner of Plays,” is on his trial—in the Court of Criticism and (to quote from Mr. William Mackay’s brilliant “popular Idol”) the Court of Common Sense. So far, we only know one side of the question, and Mr. Robert Buchanan puts it as follows:— “May I call your attention to the fact that ‘The New Don Quixote,’ a four-act play written by myself and another author, and accepted by Mr. Bourchier for production at the Royalty Theatre, has just been returned to the manager, with the intimation that it will not be licensed for representation. No reason is assigned for this high-handed measure, and the Licenser of Plays on being appealed to by me to state the nature of his objections, refers me to a clause in the Lord Chamberlain’s circular to the effect that the Lord Chamberlain has no official knowledge of ‘authors as such!’ Thus I am not only under the stigma of having written a play which is unfit to see the light, but I am unable to ascertain in what respect I and my fellow-author have offended! My opinions on the subject of the Censorship are well known, and need not be recapitulated here. I know the tyranny under which the English drama struggles to exist, and I know also how indifferent the English public is to all questions which involve the independence of art and artists; but I really did not know that the Lord Chamberlain possessed the power to suppress a play and insult an author without assigning any definite reason. The play in question is, I contend, pure and wholesome, though it deals boldly and seriously with some of the great issues of modern life. Its offence, I presume, consists in this—that it is neither trivial nor indecent in the ordinary sense; but that it is fundamentally, and not superficially, unconventional. I need hardly say that I have no intention of resting quiescent under the imputations of the Lord Chamberlain, and that I shall join issue with that functionary in the manner best fitted to justify me in the eyes of the public. Having been chosen as the scapegoat of my class, I shall accept the position, not altogether without satisfaction; for the time has come, I believe, when one man’s martyrdom may become the salvation of the English drama.” My own opinion of the function which Mr. Redford fulfils is that it is an impertinent and intolerable nuisance, and ought to be swept away. The best Examiner of Plays is the British public. Mr. Buchanan pursues his present crusade against the accident who holds the office, supported by the sympathy of every friend of healthy free trade in dramatic literature. Most of us know no more of Mr. Redford than we do of the wire worker in a puppet show. So far as his performances have gone he has shown, at any rate, than an experience of banking is calculated to make an Examiner of Plays an excessively indulgent censor. Compared with “The Novel Reader,” which was vetoes years ago, there have been plays performed which reduce that production to the level of “Old Mother Hubbard” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Has Mr. Buchanan in “The New Don Quixote” gone one better—or worse—than the authors of the works which bear the Redford stamp of approval? One is reluctant to think so, and yet to what inference is one reduced by Mr. Redford’s autocratic “No?” But there is another point concerning which everybody is agreed. Who is the Lord Chamberlain, and who is his man Friday, that they should decline to give their reasons for refusing to licence “The New Don Quixote.” They are public servants, and paid out of the public purse for what they do. The gentleman in the gallery at the Victoria Theatre was forgiving on the subject of grammar—he did not expect it—but, said he, with a pardonable conviction that he was at least entitled to that for his money—“You might jine your flats.” The Lord Chamberlain and his literary and dramatic adviser might at least be courteous. ___

[After Buchanan had made changes to the play, a licence was granted on 28th December. On 2nd January, 1896, the Pall Mall Gazette published this letter from Robert Buchanan concerning these changes.] Pall Mall Gazette (2 January, 1896 - p.3) “MR. BUCHANAN AND THE CENSOR.” To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. ___

[Buchanan gave his account of the problems with The New Don Quixote in ‘The Ethics of Play-Licensing’, published in The Theatre on 1st May, 1896.] __________

Glasgow Herald (10 January, 1896 - p.7) OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENCE. 65 FLEET STREET, . . . I UNDERSTAND that two pieces, both by Mr Robert Buchanan, are before Mr Weedon Grossmith, and that one of them will be the next production at the Vaudeville. The comedies are respectively entitled “Good Old Times” and “The Shop Walker.” They are said to be the survivors of nearly 800 plays by various stage aspirants which this unfortunate manager has had to peruse. ___

The Era (11 January, 1896 - p.10) ROBERT BUCHANAN’S PLAYS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—It is an old adage which says that the world knows more of one’s private business than one does oneself, and the truth is illustrated daily by the extraordinary statements of the theatrical gossip-monger. I see it stated in print to-day that Mr Weedon Grossmith will shortly produce one of two plays, the names of which are incorrectly given, “by Mr Buchanan.” May I ask you to state that, up to the time of writing, I have made no arrangement with Mr Grossmith to produce any work whatever, and that, in any case, I am only the part-author of any work which he may have had under consideration. I strongly object to have my business arrangements anticipated by the writers of newspaper paragraphs, and I also strongly object to have my unborn plays christened for me at the font of the Printer’s Devil. ___

The Era (15 February, 1896 - p.13) MR. BUCHANAN PROTESTS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—I had occasion, some weeks ago, to protest in your columns against the conduct of a contemporary, which presumed to label and christen certain works of mine on the eve of production. This week my anonymous assailant returns to the attack, and, in revenge for the rebuke I thought it my duty to administer, prints two statements which are written merely to do me injury. While announcing, in the first place, that a new play by myself and Mr Marlowe will shortly be produced at the Vaudeville, he is careful to add that in April next Messrs Gatti will resume possession of their theatre—in other words, that the new play, however successful it may be, will be dispossessed and compelled to seek another home. I do not know if the writer is authorised by Messrs Gatti to make this announcement, but, in any case, it is premature and in the worst of taste. ___

The Era (14 March, 1896) MR. BUCHANAN AND MR. MURRAY. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—The critics have been almost unanimous in the opinion that Mr Robert Buchanan’s “new and original comedy,” now playing at the Vaudeville under the title The Romance of the Shopwalker, is founded on the late Samuel Warren’s “Ten Thousand a-Year.” As a matter of fact Mr Buchanan is indebted to Warren for a solitary episode. The rest of his plot he has lifted bodily from a book of mine called “The Way of the World,” which was published something like a dozen years ago. _____

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—Mr David Christie Murray avers that the play The Romance of the Shopwalker, of which I am part-author, and which is now running at the Vaudeville Theatre, is a dramatic version of his novel, “The Way of the World.” Now, suggestions for The Shopwalker were certainly found in the late Samuel Warren’s famous novel, “Ten Thousand a- Year.” I have never read “The Way of the World,” and am therefore unable to discuss it; but if it at all resembles our play it is pretty obvious to what source Mr Murray must have gone for his inspiration. Surely that source was open to all of us, and if Mr Murray could go to it for the theme of his novel, why should we not go to it for the theme of our play? ___

The Era (21 March, 1896) MR. MURRAY AND MR. BUCHANAN. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—Mr Robert Buchanan is silent as to the very plain and serious charges I have brought against him. Mr Charles Marlowe’s contention that he has not read my book has no more to do with my accusation than if he were the man in the street. Mr Buchanan has read my book, and years ago suggested to me, through a third person, that he should dramatise it. Mr Marlowe’s pretence that The Romance of the Shopwalker is taken from Warren’s “Ten Thousand a-Year” proves merely that he has not even read the book from which he professes that he and his colleague borrowed their new and original comedy. Their story is not to be found in Warren’s pages. It is, as I have shown already, to be found in mine. _____

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—Inasmuch as this matter has become one of a public nature by the publication in The Era of letters from the parties concerned, one of the public may perhaps be allowed to join in the fray. Soon after the production of The Romance of the Shopwalker, I remarked to a friend that the plot was exactly like that of a novel by Mr Murray. Others to whom I have spoken have seen the great likeness between the novel and the play. Mr Charles Marlowe’s weak arguments do not clear the matter up. I agree with him that “suggestions for The Shopwalker were certainly found” in Warren’s novel “Ten Thousand a-Year;” but I do not admit the conclusion implied—that these suggestions were made use of by the authors of the play. The said suggestions are merely indirect and contrary, whereas those offered by Mr Murray’s novel “The Way of the World” are direct. On first reading Mr Murray’s book, I saw a certain likeness between his novel and Warren’s, but that likeness was an artistic and not an actual one. It seemed that whereas Warren showed from an aristocratical point of view a type of man in humble life being raised to a higher position, and put him in a ridiculous light, Murray, urged by a sense of justice, took upon himself the task of showing another side of the picture—how that, though of lowly origin and education, the hero has the instincts of a gentleman. ___

The Era (28 March, 1896) “THE ROMANCE OF THE SHOPWALKER.” TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—I had not intended to reply at all to Mr David Christie Murray, but to leave the question which he opens to public opinion. Mr Murray’s belligerent attitude, however, leaves me no option. _____

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—The letter of Mr David Christie Murray, which appeared in your issue of last week, is really too disingenuous for words, and were I to follow my own inclination I should treat it with the silence that such an effusion deserves. In adopting such a policy, however, I should be accused by that hot-headed gentleman of being unable to answer certain accusations which he has thought fit to make against me, and which, to any unprejudiced person, must appear as discourteous as they are unfounded. _____

THE DEVIL AND THE DRAMATIST. There have been so many spiteful things written about our dramatists and their literature that when a celebrated playwright brings out a serious poem the event should not be allowed to pass without comment as a publication of no importance. Almost simultaneous with the success of The Shopwalker at the Vaudeville has happened the issue from the New Temple Press of a black book called “The Devil’s Case,” by Mr ROBERT BUCHANAN. We must be allowed to disregard the plea which he makes against being judged “line by line,” and we cannot deny ourselves the luxury of a few quotations from so startling a poem. Mr BUCHANAN starts with the assertion that he has interviewed the real Devil. “I, the Interviewer, hated “I, the Interviewer, banished In spite of all tribulations, however, Mr BUCHANAN assures us that he keeps in his possession “Power to stand erect, while cravens Mr BUCHANAN’S interview with the Devil takes place on Hampstead Heath on the evening of August Bank Holiday:— “All that afternoon I’d wandered, “Sad my soul had been among them, “Since my name and fame were lying “Far down westward, over Harrow, Before we come to the interview with the Devil, we are incidentally informed of several facts interesting to all who admire Mr BUCHANAN’S talent and industry as a writer of plays. We learn that, spite of all his slips, he has ever loathed the foul materialistic serpent that surrounds the world; that, from the hour he first remembers, he was gazing at the stars, wondering, dreaming, speculating, and aspiring, and “reaching hands and feeling backward,” to the secret founts of Being. Those happy days soon passed over, and Mr BUCHANAN, so he says, became an eyeless Samson, doing his daily task-work, blind and sad, yet not despairing. Bitterly on that Bank Holiday evening—the “wolf-like creditors” thronging behind him in imagination—with all his load of woes upon him, Mr BUCHANAN bare witness against the Serpent who had made him see and know. “While the moonlight’s tremulous fingers Then, boldly announcing himself as Satan, the old gentleman—it is the “old gentleman”—clutches up Mr BUCHANAN, who clings wildly to the fringe of the Devil’s dark raiment, and is wafted swiftly away. This scene, we are sorry to say, has not been one of those selected by the artist whose exquisitely comic illustrations are the most remarkable things in this very remarkable book. “Though to other generations The “great original” in this case seems to have been SAMUEL WARREN. As regards the MURRAY - BUCHANAN - JAY controversy we must leave opinions to be formed by each of our readers according to his lights and data. Let us hope that in the end all may be satisfactorily explained, and that each of the three laurel-wearers may wander “stainless” and “innocent”—though certainly not “nude.” ___

The Era (4 April, 1896) “THE ROMANCE OF THE SHOPWALKER.” TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—At last Mr Robert Buchanan has entered the ring. I could ask for nothing better.

[Samuel Warren’s Ten Thousand a-Year and David Christie Murray’s The Way of the World (Vol. 1 and Vol. 3 only) are available at the Internet Archive. The Romance of the Shopwalker was never published. Personally, when first reading the reviews of The Romance of the Shopwalker the first thing I thought of was Kipps by H. G. Wells (to tell the truth it was actually Half a Sixpence with Tommy Steele) but, on checking the dates, that was published in 1905. One wonders where Wells got his idea from. David Christie Murray (1847-1907) was the elder brother of Henry Murray, who had lived for a time in the Buchanan household (and whose suggestion that people would pay good money to see Lily Langtry dance led to their collaboration on A Society Butterfly which was the immediate cause of Buchanan’s bankruptcy in 1894) so he would obviously have been at least a casual acquaintance of both Buchanan and Harriett Jay. He makes no mention of Buchanan in his books, The Making of a Novelist: An Experiment in Autobiography (1894), My Contemporaries in Fiction (1897) or Recollections (1908), but the latter does contain transcripts of two letters from Buchanan, one of which is dated 17th June, 1897 and appears quite friendly in tone, suggesting that whatever animosity was caused by the Shopwalker incident had been forgotten. I came across two items in The Boston Globe from October 1894, concerning David Christie Murray, who was visiting America at the time, which contain brief mentions of Buchanan. The first of these is on the subject of palmistry (!), the second, a review of a public performance by Murray - both are available below.] |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Letters to the Press - continued or back to the Letters to the Press menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|