ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LETTERS TO THE PRESS (16)

The Case of Rayner and Eggleton

Daily News (14 March, 1892) LETTERS TO THE EDITOR. A PLEA FOR MERCY. SIR,—So absorbed are we Londoners in the contemplation of our own small universe, of our social vanities, our municipal struggles, and our causes célèbres, that we know little or nothing of what is taking place outside our city in the England of to-day. With barbarism reaching to our very gates, and with feudalism still surviving in the remote corners of the land, we exist in self-satisfied content, save when distant rumours of troubles in Ireland or of coal strikes in the north come to disturb our serenity. It is only at the last moment, therefore, and almost by accident, that I have heard of a criminal trial, which took place some weeks since at Aylesbury, and which resulted in the conviction of two men for wilful murder. The men are now lying in the county gaol at Oxford, and unless the plea for mercy which has been forwarded to the Home Office should be granted they will be executed on Thursday next.

[Note: This letter was also published in The Daily Telegraph on the same date.] ___

Daily News (15 March, 1892) A PLEA FOR MERCY. SIR,—Unless through your columns, I have no means of reaching those who have taken up the case of Eggleton and Rayner, condemned to execution on Thursday. The answer of the Home Secretary to my question to-day was eminently unsatisfactory. We members here have not sufficient evidence before us whereon to base possible further action—difficult enough under any circumstances. A full report of the trial as given in The Aylesbury Reporter should be circulated. If the case is as simple as stated by Mr. Buchanan in to-day’s Daily News, a vigorous effort should be made to save the men—if indeed it would be a mercy to save them to penal servitude.—Yours sincerely, ALFRED WEBB. _____

SIR,—Mr. Robert Buchanan in his plea for mercy on behalf of the men Eggleton and Rayner, condemned to be executed on Thursday for the murder of two gamekeepers at Aldbury, while evidently actuated by the best intentions, is not quite correct in one or two points. Having traversed all the circumstances of the situation, I may say that Eggleton, a hay and straw binder, said to have “neither food nor money at home for his wife and children,” earned 4s. or 5s. a day at his work, and on the evening in question the evidence given shows that he primed himself with beer at more than one public-house, as did Rayner and Smith. Mr. Buchanan relies perhaps too implicitly on the statements made by the men themselves. After all, however, it is obvious that there was a conflict between the poachers and the keepers, in which one of the latter was evidently killed while retreating by blows on the back of his head. It may be admitted that some blame is due to the game laws. Probably there was bad blood between both poachers and keepers, who were well known to each other, that the poachers did not mean to be taken, and that the keepers meant to capture them. Mr. J. G. Williams personally is known as a very kind-hearted man. Some 1,500 signatures for the reprieve of the men have been given to a memorial, and The Aylesbury News is probably correct in saying that “Much satisfaction would be felt in Aylesbury if the Home Secretary acceded to the wishes of the large number of persons who have petitioned for the reprieve of the men.” I visited the homes of both Eggleton and Rayner last week. Eggleton’s wife and six children under thirteen I found in a four-roomed house at New Mill, Tring. Rayner, a well-informed neighbour told me, was a “most kind- hearted man.” My one impression throughout was that the result would be conviction for manslaughter, as I told our Deputy Chief Constable, who since the sentence said: “You were wrong in your forecast.” Two or three of the Tring ministers are interesting themselves on behalf of the men, and there is an increasing feeling that the men should be reprieved.—Yours, &c., G. LOOSLEY. _____

SIR,—The letter of Mr. Buchanan entitled “A Plea for Mercy,” which appears in your impression of to- day, is one that is worthy the earnest attention of every one possessing a human heart. The case of the men Eggleton and Rayner, now lying under sentence of death, is pitiable in the extreme, and the circumstances of the fatal affray which placed them in this position ought to be widely known if any effort is to be made to save their lives. Surely here there was an entire absence of that “malice aforethought” which can alone at any time make the capital sentence at all justifiable; and a verdict for manslaughter would have met every need. Is there not some excuse to be found for “a man in sore distress, who has no food for himself, his wife, or his children,” and who in the search for such strikes a blow that proves fatal to the man who would prevent him? Murder is not to be condoned, but this case is not one of murder; and the powers that be would do well to recall the truth that “earthly power doth then show likest God’s when mercy seasons justice.” If this barbarous custom of capital punishment must of necessity tarnish our national good name for a short time longer, then in the name of all that is just and good, let us plead that murder alone may be punished by it, and that something short of “a life for a life” may be the award for other crimes.—I am, Sir, faithfully yours, _____

SIR,—Seeing in your paper to-day Mr. Robert Buchanan’s letter with the above heading, I beg leave most earnestly to support his plea. If the facts were as stated by Mr. Buchanan, not only must the offence of these men be reduced to manslaughter, but to manslaughter not of the worst kind, since it was probably committed in self-defence against men who themselves began the affray by an illegal assault. For though gamekeepers discovering poachers in the act of pursuing or killing game are legally entitled to take them into custody, they are not, I believe, entitled to use violence of any kind unless the poachers refuse to submit after being called upon to do so. But gamekeepers are so systematically supported in all their acts of violence against poachers by magistrates who are usually themselves game preservers, that they look upon poachers as men who are altogether outside of any protection by the law, and who may therefore be attacked and violently assaulted without notice and with complete impunity as regards any action of the law against themselves. I presume the three men were personally known to the keepers, in which case there was no justification whatever for assaulting them, as they could have been legally apprehended the following day. Believing that our game laws are utterly immoral and unjustifiable, I earnestly support Mr. Buchanan’s plea, not for mercy only, but for such a moderate term of imprisonment as will satisfy the demands of justice, giving to the condemned men the benefit of every reasonable doubt in the case.—I am, &c., ___

Pall Mall Gazette (15 March, 1892) THE CULT OF THE SACRED BIRDS. IF the Home Secretary makes no sign between now and Thursday the tragedy which began with the shooting of one pheasant at Pendley Manor will end in the hanging of two men at Oxford Gaol. The facts of the case have already been made familiar to the public by Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN, and we need only very briefly recapitulate them. On the night of December 12 three men—SMITH, EGGLETON, and RAYNER—the first two labourers, and the third a chair-turner, went poaching on the estate of Mr. WILLIAMS, of Pendley Manor. RAYNER fired at a pheasant and missed; EGGLETON fired at the same bird and hit it. Almost immediately two gamekeepers rushed upon the men, and a fight to the death ensued, in which the two keepers were killed, and two of the poachers more or less hurt. All three men were captured, tried, found guilty, and sentenced—two to death, and one to penal servitude for 20 years. It availed the men nothing to plead that they were first attacked and had done what they did in self-defence. There was no one to corroborate the story, nor, if proved up to the hilt, would it have made the slightest difference at law. The man who causes death in the process of committing a felony is guilty of murder in the legal sense, whether the act was one of malice prepense or not. As the law stands, neither judge nor jury had any option about the result at the Aylesbury Assizes. But the Home Secretary has an option, and it is precisely in cases of this kind that he is expected to exercise his option. It is nothing to Judge and Jury that the men were destitute, that they acted in the heat of a sudden mêlée, and perhaps in self-defence, and that the felony which they were committing was the shooting of a pheasant. But these kind of considerations are everything to the public, and should be everything to the Home Secretary. They make the whole difference in estimating the moral guilt of the crime, and we have not in this country such a comfortable assurance about the efficacy of the gallows that we can stand by and see two men executed until we are quite positive that their crime is murder positively and morally as well as legally. Cold-blooded poisoners and unmitigated assassins of the same class have so often received the benefit of a doubt during recent years that a case of this kind should appeal with special force to the Home Secretary’s discretion. As Mr. BUCHANAN well says:—“In mitigation of the extreme penalty, it should be remembered (1) that the fatality occurred during a desperate struggle, in which the angry passions of all concerned were aroused; (2) that the first savage blows were struck by the keepers, armed for that purpose; (3) that the poachers acted, at least partially, in self-defence, and to avoid capture; and (4) that the real right and wrong of the whole business could be known to no living soul save those men whose lips were practically closed.” Killed outright ....................................... 2 This grim table is worth careful consideration. let us assume that what Mr. HERBERT calls the Sacred Birds of England require some veneration. But are they really, unlike the sparrows, of more value than many human lives? Is the cult of them indeed worth the cost? ___

[Note: I have placed the following item here, out of chronological sequence, since it quotes another letter from Buchanan to The Echo published on Tuesday, 15th March, 1892. The article begins with a reprint of Buchanan’s first letter of 14th March to the Daily News and other papers, and after the following reprint of the Echo letter, goes on to quote other letters and deal with other matters related to the case. The full article is available here.] The Herts Advertiser and St Albans Times (19 March, 1892 - p.7) THE ALDBURY MURDER. . . . The following letter on this subject appeared in the Echo of Tuesday evening from Mr. Buchanan: ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (16 March, 1892 - p.2) IT is not often that the advocacy of Mr Robert Buchanan does any good to a cause, but it must be admitted that in the appeal he has made on behalf of the two men lying under sentence of death for the murder of a gamekeeper, he has made out a good case. He points out that the fatality occurred during a desperate struggle, that the first blows were struck by the keepers, that the poachers acted at least partially in self-defence and to avoid capture, and “that the real right and wrong of the whole business could be known to no living soul save to those men whose lips were practically sealed.” Mr Buchanan therefore contends that to carry out the death sentence in such a case would be “a national scandal.” He also argues that the last penalty of the law should not be inflicted except in cases of wilful and deliberate crimes, and in holding this opinion he certainly does not stand alone. Capital punishment ought certainly to be reserved for cases where premeditation has been clearly proved. In the United States no judge can impose the death sentence except when the criminal has been found guilty of murder in what is called the third degree; and were such a restriction in existence in this country, we would be saved many an unedifying agitation for a reprieve, when the criminal happens, on account of special circumstances, to arouse popular sympathy. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (17 March, 1892) VICTIMS TO THE SACRED BIRDS. EXECUTION OF THE POACHERS. BRAVE DEMEANOUR ON THE SCAFFOLD. The two men named Rayner and Eggleton who were sentenced to death for the murder of two gamekeepers at Pitstone were executed at Oxford this morning. Billington was the executioner. _____

THE SACRIFICIAL RITES. THE condemned poachers have been hanged this morning in Oxford jail, and the death-roll has thus been raised to five. First, there was killed One Sacred Bird. And in the vindication of its sanctity, directly and indirectly, there have now been slain Four mere Human Beings. The terrible costliness of these Sacrificial Rites on which we have been insisting has, we observe, already come home, as their grim force could not but make them go, to men’s judgments and consciences in many quarters. But, as is inevitable when the public feeling is deeply touched, there are also many signs of a confusion of thought in the matter; and such confusion is a danger, for the devotees of the Sacred Birds will take advantage of it, we may be sure, to repel the discredit which we have sought to attach to their Cult. In this morning’s Standard, for example, we find an instance. “If,” we are told, “a man chooses to combine murder with poaching, he cannot be absolved from the former offence because he has been guilty of the latter one.” This is perfectly good logic; but it only avails in defence of the Cult of the Sacred Birds by utilizing a confusion between two distinct points which have been raised in the case—first, was there substantial, and not merely constructive, premeditation in the case? If there was not, then it might fairly be argued that the men who were hanged this morning were directly martyrs to the Game Laws. If there was, then the Standard’s point is a good one. But in this latter alternative there remains, secondly, the question whether the preservation of game is worth the sacrifice of life—the life of keepers, no less than that of poachers—which it inevitably entails? This is not a legal question, but a moral one—one of expediency, not of principle. The pheasants on this particular estate will doubtless be safe for some time to come now; but was their preservation worth its cost? _____

THE CULT OF THE SACRED BIRDS. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—By the time this letter appears (if permitted so to do) the two men condmned at Aylesbury will have probably suffered the extreme penalty of the law. To those acquainted with the facts of the trial the sympathy for their fate seems somewhat misplaced, apart from any question of the maintenance of the game laws or capital punishment. It is argued that the men were attacked first. Doubtless. Two keepers, unarmed except for sticks, coming at night upon three poachers, two armed with guns and one with a heavy bludgeon, must either make the first rush or run away. When one keeper fell and was being beaten to death, the other ran. He was pursued by the two men and struck on the back of his head with such force as to smash in the skull. Assume that these men were caught in a most venial offence, how does that affect or modify the murderous spirit shown—with what motive? Merely to avoid the consequences of recognition by the keepers. Suppose those consequences had been six months’ hard labour? Sympathy might have been reasonably evoked, and the disastrous effect of the game laws effectively illustrated. In the present case a far more worthy argument is the hardship of exposing two necessarily unarmed keepers to such terrible consequences for the sake of protecting the “one pheasant.”—Yours respectfully, _____

To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—About “those sacred birds” and the general reign of stupidity of which they are the emblems, I should be glad to write a few words of explanation, if you care for me to do so. I do not want to suppress in any forcible manner either the sacred bird itself or any law which gives reasonable protection to it. My creed goes against all such suppressions. I would not suppress any of the temptations or stumbling-blocks to which human flesh is exposed. Drinking-house, gambling-house, prize-fighting establishment, evil literature, house of low amusements, or of ill-repute—much less would I suppress, the sacred bird or any of the many costly rites with which he is so devoutly worshipped. Why? Not simply because I know that I have no right to decide any such matter for other people, but also because I can see that we only improve in mind and character by living in presence of all the snares of the flesh and learning with our own free consciousness to avoid them. I hold that the evil—till it dies out-worn—is as necessary for our teaching as the good itself. True progress in character is unthinkable if you root up all the thorns and brambles which you see around you, and their place is to know them no more. We must never forget that evil is always working for good through its reactions. This world, as has been said, is God’s manufactory of mind; and the manufacture cannot go on except by the free intermixing of all forms of good and evil. I know that in saying this I am preaching to those who are little inclined to listen. The energetic part of the world at present is hot in the cause of suppression. It hopes to purge the floor with fire; it hopes to carve and trim in its own pattern human nature, like the yew trees of our great-grandfathers; it hopes, as in Hawthorne’s story, to cast all things of offence into the fiery pit, and forgets that the human heart still remains behind, unchanged, to trouble the human race. But the pendulum will presently glide back, and the love of and belief in liberty he born anew.—Very faithfully, (But at what precise point does Mr. Herbert accept the whole body of the existing state of things as beneficent and sacrosanct evil? We can understand his not wanting to suppress the sacred birds; but why should the laws giving them special protection be also exempt from suppression?—Ed. P.M.G.) ___

Daily News (18 March, 1892) THE MURDER OF GAMEKEEPERS. EXECUTION OF THE POACHERS. Frederick Eggleton, thirty-five, and Charles Rayner, thirty-one, were hanged at Oxford yesterday morning, for the murder of Joseph Crawley, gamekeeper, and William Puddephatt, assistant-keeper or “night-watcher,” at Pitstone, near Aylesbury, on the 12th of December last. Billington, the executioner, entered Eggleton’s cell at five minutes to eight, and, after pinioning him, proceeded to an adjoining cell, in which Rayner was confined, and quickly performed a similar operation. Both convicts wished Mr. Pullan, the chief warder, “Good-bye” before leaving the cells, and thanked him and the Rev. J. Knight Newton, the chaplain, and the officials generally for their great kindness to them during their incarceration. The procession was then formed, the chaplain reading the service commencing “I am the resurrection and the life.” Rayner preceded his fellow-convict. After traversing a corridor fifteen yards long the drop was reached, and the men took their places under the beam. Both showed great firmness, and repeated with fervency responses to the chaplain. In about half a minute the bolt was drawn and the culprits disappeared. There was afterwards not the slightest perceptible movement of the bodies. Rayner, who was slightly the taller, had a drop of 7ft., while Eggleton was given 3in. less. They both wore the clothes they had on at the trial. After the lapse of a few minutes Dr. O’Donovan descended into the pit and pronounced life in each case to be extinct. ___

The South Bucks Standard (18 March, 1892 - p.5) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, the well-known author, with his usual impetuosity, has rushed into print regarding the fate of Eggleton and Rayner, who were condemned to death at the last Assizes at Aylesbury for the murder of the two gamekeepers at Aldbury, and who were executed at Oxford yesterday morning. He defends the two murderers against the extreme penalty by a tirade against the game laws, but surely whatever we may think of the game laws cannot palliate the offence for which Eggleton and Rayner have paid the penalty. As long as the game laws exist, keepers are simply the innocent instruments by which they are carried out, and if such men as Eggleton and Rayner are to be reprieved, then it would be an encouragement for blackguards of the poacher class to make murderous attacks on keepers on any pretext. Mr. Buchanan says the men only acted in self-defence, but what does he call self-defence? The murderers were by their very presence at the spot in question, committing an illegal offence, and the keepers, as was their duty, attempted to arrest them, and will Mr. Buchanan tell us that resistance to arrest for unlawful acts is to be considered justifiable self-defence. If this be held so, then it opens a very wide door indeed, and the policeman will no longer be safe in arresting a burglar or a murderer, as he may have his brains beaten out in self-defence. This is sophistry with a vengeance. I am sorry to see that the custom of allowing sentiment to interfere with justice in England is greatly on the increase. ONCE Mr. Buchanan had set the ball rolling there was not of course wanting many other sentimentalists who joined him in writing letters to the newspapers, and bringing pressure to bear on Members of Parliament to ask the Home Secretary questions on the subject in the House of Commons. Mr. Matthews has been besieged with questions, and when on Wednesday he finally completed his painful duty by expressing his inability to interfere with the course of the law, the House was adjourned and he was assailed with a long string of questions, not altogether free from abuse, because he had not thought fit to act in the way in which some sentimental enthusiasts would like to see him. Then such organs of Radical opinion as the Star and the Daily News have heaped anathemas on his head for the same reason, but criticism from such a source indicates, I fear, a desire to make political capital even out of so painful a matter as this. To imply that Mr. Matthews is guilty of judicial murder, as Mr. Conybeare did in the House of Commons on Wednesday night is arrant nonsense. Why should Mr. Matthews wish to murder judicially men who had never done him any harm? I cannot help feeling that it is a real scandal that men on whom so fearful a responsibility is placed as rests on Mr. Matthews, should be abused and badgered, and their responsibility made doubly painful, when they have conscientiously tried to do their duty. AS Mr. Matthews himself pointed out, it was the jury who had decided this case to be murder, and not himself. The application made to him as her Majesty’s adviser was to see whether there was any real and substantial ground for recommending mercy notwithstanding the verdict of the jury. That was his duty and he has given precisely the view at which he had arrived after the most careful study of the case. What more can any man possibly do? To heap contumely upon him because he did not set aside the verdict of the jury, is as cowardly as it is contemptible. Eggleton and Rayner were executed yesterday morning, not primarily, because of any action or inaction of the Home Secretary, but because they were found guilty of murder by twelve of their countrymen. One of the jurymen, it is alleged, has written to the Home Secretary supporting the petition for a reprieve on the ground that he and some other jurymen desired to bring in a verdict of manslaughter, but gave in to the majority of the jury. But to my mind that only reflects upon the juryman himself. If he conscientiously believed that the men were only guilty of manslaughter, then he should have held out against a verdict of murder being returned, whether the majority were against him or not. The Home Secretary could only deal with the verdict of the jury as a whole, and because a juryman chose to put his signature and assent to a verdict with which he did not in his heart agree, is entirely his own fault and surely not the Home Secretary’s. IT has been pleaded that the fatal blows were struck in hot blood. At the best, this would be an excuse, not a defence. But what are the facts? One of the keepers whom the men had injured attempted to get away; they pursued him and killed him in his flight. Here is a deliberate act of murder, committed not to save themselves from immediate arrest, but in order to destroy any future evidence against themselves. Where are we to look, then, for any extenuating facts? ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (18 March, 1892 - p.2) THE POACHERS’ EXECUTION. Mr Robert Buchanan, writing under yesterday’s date to the “Daily Chronicle” with reference to the executions of the poachers, Rayner and Eggleton, says:—The judicial murder committed this morning on the unfortunate poachers of Aylesbury leaves another blood stain on our so-called Christian civilisation. I need not hesitate to express, as I have done on more than one occasion, my opinion of the man who is known, and rightly, as “the hanging Home Secretary.” But it is useless to traverse all Mr Matthews’s sophistries. It is enough to know that he has again covered himself and his party with both legal and moral disgrace, that he has again shown an absolutely cold-blooded indifference to all sanctions save those of landlordism and property together with a pitilessness worthy of the cruellest provisions of the old Roman law. Let this last legal murder be remembered as their crowning infamy. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (18 March, 1892) THE CULT OF THE SACRED BIRDS. IS IT WORTH THE COST? NO, SAYS THE GOOD SQUIRE. Mr. E. C. Bird writes to the Chronicle from Ivy House, Tring:—From your leading article on the above subject it is clear you know nothing of the squire you there rate so severely, and consequently have formed a most erroneous conception of his character. Having known him from boyhood upwards, I can vouch for him being one of the kindest hearted and most generous of men, and who was in no way responsible for the acts of his over-zealous servants, whom you state were proved to have struck the first blow. Indeed, he was so affected on learning what had occurred that he at once resolved to give up game preserving, and exerted himself to procure situations for those thrown out of employment in consequence. A LETTER FROM MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. Mr. Robert Buchanan writes to us:—The judicial murder committed on the unfortunate poachers leaves another bloodstain on our so called Christian civilization. I was careful not to imperil their last chance of respite by one word which might arouse the personal prejudices of Mr. Matthews; but now I need not hesitate to express my opinion of the man who is known as the Hanging Home Secretary. In his answers to the questions put to him in the House Mr. Matthews betrayed either total ignorance or absolute perversion of the facts of the case. He stated, for example, that the poachers pursued one of their victims when he was running away, and killed him when lying on the ground: a statement absolutely without any foundation, save the suggestion of the counsel for the Crown and the remark of the surgeon who examined the body that “the wounds might have been (he could not say they were) inflicted when the man was on the ground.” MR. MATTHEWS AND THE JUDGE. Shame must fall upon the cowardly jurors who, believing a verdict of manslaughter would meet all the circumstances of the case, were weak enough to yield to their pertinacious brethren. Shame should fall also upon the judge, who imperatively refused to consider the crucial legal points raised by Mr. Trevor White, and who, at 5.30 on the day of the trial, declined an application for adjournment till the next day. It was not until ten o’clock at night that the jury, wearied out after sitting from 10 A.M., agreed upon their verdict. Let it be noted also that it was with Mr. Justice Lawrance only —with the judge who even in presenting the case to the grand jury had shown strong animus against the prisoners—that Mr. Matthews consulted respecting my plea for mercy! Is it not significant that every one of these journals which declined to say one word for the unhappy men is the organ of landlordism and the mouthpiece of the reigning Government? Once again, in the eyes of our privileged classes, justice is nothing, humanity is nothing, mercy is nothing, compared with the preservation of birds for purposes of the cowardly battue. Let it be remembered, however, throughout this kingdom that the disregard of those sacred verities comes from the party which will soon, we know, be drummed out of office. Let this last legal murder, I say, be remembered as their crowning infamy. THE “MOCKERY OF THE ROYAL PREROGATIVE.” One point remains to be considered—the mockery and the paradox of a system which transfers the Royal prerogative of mercy to an irresponsible Minister in the people’s pay. At what price shall we appraise the functions of the Queen of England? She is a woman, a wife, and a mother. Only the other day the nation plunged itself into mourning at her bidding. A moment came when men might have said: “After all, there is wisdom in our Constitution—the beneficence of a Ruler may qualify, now and again, the infirmities of party and the brutalities of law.” What folly it is to talk of a prerogative which Royalty cannot, or will not exercise! Why continue the mockery of monarchy at all, if monarchy, having long ceased to be useful or ornamental, is not to be a supreme refuge—on occasions of national despair? Had the Queen of England lifted her little finger this legal murder would never have been committed. But she did not, or she could not; and the people, clamouring for the waters of mercy and humanity, had to seek them in the dry well of a political party, among the wretched formalities and legal quibbles of the Home Office. A VICAR’S PRONOUNCEMENT. Speaking at a meeting at Folkestone last night the Rev. Russell Wakefield, vicar of Sandgate, said that he never felt a more earnest belief that we had erred as a nation in the execution of the two poachers. It gave one the impression, however unwillingly, that there was something sacred about the preservation of pheasants. The result must be to soon kill the Game Laws, unless such painful results were prevented. _____

OCCASIONAL NOTES. It seems from a letter which we quote elsewhere that the question we have been asking for the last few days about the Sacred Birds has already been answered by the squire on whose property the latest victims were sacrificed. He did not approve, we are told, of the over-zeal of his keepers; and was so shocked by the tragic occurrences that he resolved there and then to give up game preserving, and has already made provision for the keepers and others thrown out of employment thereby. All honour to the “Good Squire” who has thus determined to wipe out the taint of blood of which Kingsley spoke in “The Bad Squire”:— There’s blood on your new foreign shrubs, squire, __________ Of course we do not mean to say that every game-preserver is a “Bad Squire.” There is, we admit, a great deal to be said on the other side; especially, as we pointed out yesterday, if the case be argued—as our correspondent, Mr. Longman, argues it with much force and good feeling to-day—on the pheasant. But Mr. Longman hardly tackles the real point. let us grant him, for the sake of argument that it would be debasing the moral currency for the law not to recognize property in wild animals as much as in silver spoons. He, on the other hand, can hardly refuse to grant us that the temptation to poach is greater and more excusable than the temptation to steal. On this state of facts, then, can a case be made out for the special protection given to wild animals as against silver spoons?—for those game laws which inevitably lead to such bloody savagery as that which has caused the squire at Pitstone to renounce in horror the Cult of the Sacred Birds? __________ Instructive:— |

|

|

|

Decidedly Mr. Auberon Herbert was right when he made an Editor one of the party assembled at “Fesantia Hall” to worship the Sacred Birds. __________ Recent events have not at all tended to the glorification of the gallows. The ex-hangman is doing all he can to prove that hanging is a relic of a barbarous age which ought to disappear from civilization long before the century closes. But the execution of the murderer Schneider was almost as brutal as the man’s own crimes. The white silk cord having been adjusted, The executioner placed his left hand upon Schneider’s jaw and mouth, and his right over the forehead and eyes, and commenced pressing vigorously. One of the assistants meanwhile hung on to the hands of the culprit, and the other, kneeling on the ground, seized his legs, both hands being pressed downwards with his whole weight. Under the grasp of three such powerful men the doomed criminal was unable to move, and the doctors state that he was dead in four minutes. Hanging is very seldom resorted to in Austria, and after this no one need be surprised. The “electrocutions” in America may not have been very successful, but, at any rate, they were experiments towards a better way of doing criminals to death than obtains in most European countries. _____

THE GAME LAWS. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—Your articles on the lamentable occurrences at Pitstone have again brought into prominence the question of the Game Laws. In discussing the matter you have rightly kept separate the two points at issue, namely, the question whether or no Rayner and Eggleston were guilty of wilful and deliberate murder, and the question whether or no the system which undoubtedly led to the murders is worth maintaining. On the first point you admit (having, I gather, at first taken the opposite view) that Mr. Matthews made out a convincing case. It would not seem to be any great praise to say that a journal is open to conviction, and willing to admit that a political opponent may have right on his side. In the Pall Mall Gazette I may say, without being suspected of flattery, that one expects this amount of candour, but unfortunately there are not many journals in which such fairplay is common. Perhaps I may be allowed to add, as being myself a political opponent of Mr. Matthews, that his courage in doing the unpopular thing on the eve of a general election has earned him much respect. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (19 March, 1892) “THE CULT OF THE SACRED BIRDS.” FROM the mass of correspondence which we have received on the subject of the Pitstone poaching case, and of the general question of the Game Laws raised thereby, we are only able at present to find room for the following:— To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—I have nothing to do with the judicial or the political side of this question. There is another and a very dark one. Three women and twelve children—all innocent—have been left totally unprovided for. We are trying to raise a fund on their behalf, and if any of your readers feel inclined to subscribe small sums either the Rev. Charles Pearce, Tring, Herts, or myself will be glad to receive them.—I am, Sir, yours respectfully, _____

SIR,—It is very kind and good of Mr. C. J. Longman, who is a publisher of books, to draw a parallel between the case of the game-preserver and that of the author. The parallel is scarcely flattering to those who, like myself, live by writing. Until enlightened by this supreme authority, who bears the same relation to Literature that the game-seller does to Sport, I never realized the wickedness and selfishness of Authorship: I was rather under the impression that literary “preserves” were less private property than green spaces where the critic might carry his gun, and “pot” his game, without fear of personal assault and battery. “Literary property,” says Mr. Longman, “is even more difficult to define than game,” by which he simply means that, until lately, Americans recognized no rights in the first-named commodity. It is refreshing, in the nineteenth century, to find an amiable publisher, or literary game-dealer, who classes the production of books with the rearing of pheasants; who would doubtless regard an author who “poached” an idea as a wretch worthy of penal servitude; and who would encourage the author, or literary game-preserver, to assault and maltreat any trespasser on his domain. I like this; as Whitman says, “it tastes good.” Henceforth I may safely batter a plagiarist, or even a critic, and if the battered individual kills me in the discharge of my sacred duty, why, he’ll swing for it, without any hope of respite from the Home Secretary! _____

SIR,—Will you allow me to draw your attention to a result of the game laws, not so tragic as the death of keepers and the hanging of poachers, but one which prejudices the rights—as many think them to be—of the public? I refer to the closing of footpaths and mountain roads, particularly in the Highlands of Scotland. _____

SIR,—I would not suppress the law that protects “the Sacred Bird,” because I hold that the impartial defence of property and person being the one true function of law I have no right to ask myself whether I admire the purpose to which such property is applied. About this defence of person and property we are all of us constrained to agree. It is the necessity of the party of Liberty as much as it is the necessity of other State-parties, whether of progress or of order. Even the group of moderate and reasonable Anarchists speak of associations and local juries for defence; and unless you accept the splendid though terribly difficult doctrine of Count Tolstoi, you cannot escape from undertaking this defence. The only question is, shall the defence be impartial, universal, outside and above all personal predilections, and founded on distinct principles; or shall you and I pick and choose at our pleasure, selecting just what we fancy at the moment to protect or to leave without protection? Between these two courses I cannot hesitate. I would protect universally and impartially, not simply because such impartial protection represents to my mind justice, as partial protection represents injustice, but because I have such an intense belief in every kind of property. I would not cut off from land or any form of private property the very minutest fraction of any right that rationally belongs to it. We have often talked of the magic of property, but we have never yet, in any true fashion, pictured to ourselves what power that magic might possess. Let land be untithed, untaxed, free both from official interferences and the still terrible legal complications that cluster round it, and you would have a natural force acting upon the people, upon their character and their industry, to which all legislative nursing and protective inventions are but child’s play. No nation has yet given property—combined with liberty—a fair chance of exerting the influence that belongs to it. Property tends everywhere to become mere tax- material, and as the official waxes, the people wane. Whenever we set the giant free of his toils, and he gets fairly to work on our behalf, a new era will begin, and we shall be able to suspend with a light heart the larger part of our huge parliamentary industries.—Very faithfully, ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (19 March, 1892 - p.4) The Radicals and other puzzle-headed mortals, including Mr. Robert Buchanan, continue to mix up the execution of the Tring murderers with the Game Laws, after a fashion that, when dealing with such a grave matter, is utterly unjustifiable. They appear to have really convinced themselves that the men were hung for breaking the Game Laws. Not a word is said about the murdered men who, it is to be presumed, had wives or other relatives to mourn their deaths. Mr. Buchanan, not content with attacking judge, jury, Home Secretary, and all the privileged classes, now carries his assault up to the House itself. “Had the Queen of England lifted her little finger this legal murder would never have been committed.” And the allusion to the recent Royal mourning is in the same questionable taste. ___

The Illustrated London News (19 March, 1892 - p.7) There has been much discussion of a protest by Mr. Robert Buchanan against the sentence of death on two of the Aylesbury poachers. It is alleged that they were assaulted by the gamekeepers, heavily armed, two of whom were killed in the mélée, not deliberately murdered. As the poachers must have been perfectly well known to the keepers, it is hard to understand why the latter were not content to arrest them in their homes next day, or put the police on their track. But it is one of the peculiarities of the Game Laws that they must be upheld by armed force, and that poachers must be killed or taken on the spot. This is a system of which public opinion is a little weary, especially as the unlimited preservation of game is a constant temptation. If a man knocks over a pheasant, it is rather barbarous that he should be liable to have his skull stove in by a keeper, unless he can do the same for his assailant. This is not law, but social war. ___

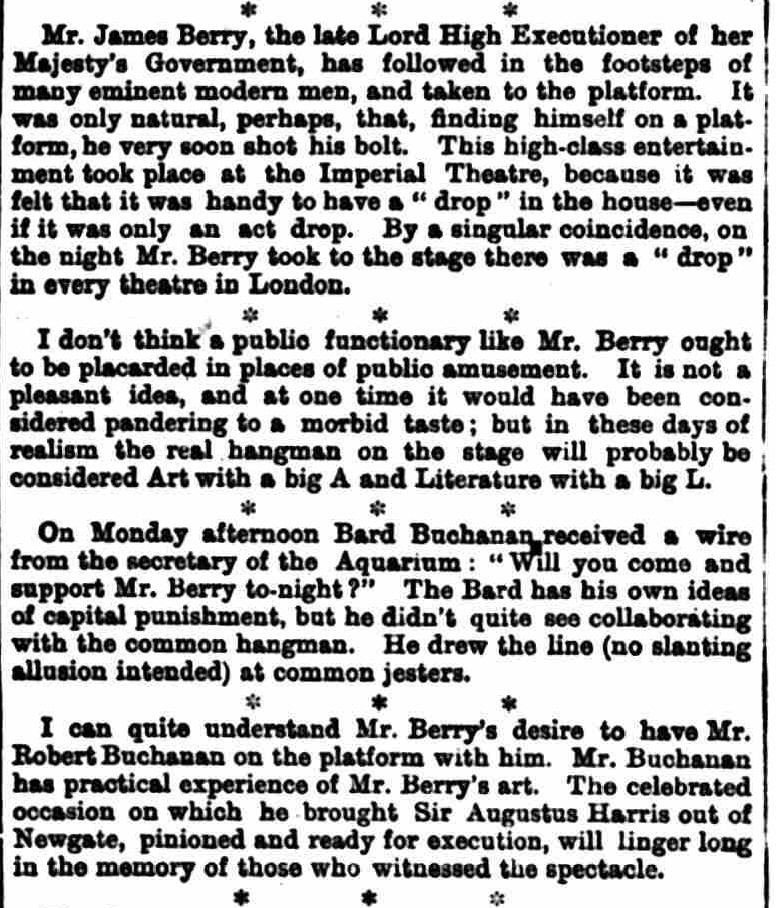

The Penny Illustrated Paper (19 March, 1892 - p.9) ROUND THE COURTS DROPPING into the Strand Law Courts and the Old Bailey, peeping into Police Courts, and even suffering the infliction of a visit to a draughty theatre, one of the riskiest of undertakings during this Siberian weather in town, the ubiquitous P.I.P. Artists have not spared themselves in their efforts to keep our readers au courant with the chief notabilities in legal and criminal circles. Room first, however, for Mr. James Berry, |

|

|||

|

who has felt bound to resign the office of public hangman in favour of the vocation of public lecturer on the gentle art of hanging. The P.I.P. Artist caught Mr. Berry making his maiden effort as a lecturer at the Imperial Theatre, adjoining the Westminster Aquarium, last Monday night. It appeared from what he read that the late chief executioner had too tender a heart for his occupation. His kind solicitude for the comfort of the poor fellow-creatures whom it was his painful duty to launch into another world induced him to devise various improvements in the hangman’s dread apparatus. But Mr. Berry favours the abolition of capital punishment, and a resolution to that effect was put to his audience and approved by a majority of those who cared to hold up their hands. This majority may not improbably have been influenced by the fervid and well- grounded appeal Mr. Robert Buchanan made in the Daily News of Monday for the reprieve of Rayner and Eggleton, two men sentenced to death at Aylesbury for killing two keepers during a poaching encounter, in which the latter appear to have been the first aggressors. Mercy might well be shown in this case. ___

The Referee (20 March, 1892 - p.7) (From G. R. Sims’ ‘Mustard and Cress’ column.) |

|||

|

|

The Galveston Daily News (19 March, 1892 - p.2) Stirred Up a Storm. LONDON, March 18.—The Chronicle, commenting on the execution of the poachers, says: The callous folly of Home Secretary Matthews has lost the government thirty seats in the rural districts. He has shocked the conscience and affronted the reason of a vast majority of his countrymen. ___

The Bucks Herald (19 March, 1892 - p.5) [Click the picture below for more information about ‘The Pitstone Murders’.] |

|

|

Reynolds’s Newspaper (20 March, 1892) SPECIAL NOTES. THE due share of responsibility for the judicial murder of the two poachers must, as Mr. Robert Buchanan honestly and manfully points out, lie with Queen Victoria as well as with Henry Matthews. Queen Victoria’s slightest word could have saved these two men’s lives. The obsequious Matthews would have yielded at once, and the country would have been saved from a burning disgrace. But that word Queen Victoria did not take the trouble to speak. This selfish woman was busy packing up for Hyères, receiving accounts of how the donkey had stood the long journey, and what were the lives of two poor men to her? The utter uselessness of the Throne was never more clearly proved, for if the crowned woman, with her £385,000 a year and her palaces, is of the slightest good at all, it might have been in a case of this kind, where no political question, but the merest dictates of common humanity were concerned. But Queen Victoria, whose elderly heir slaughters pheasants by the hundred to kill time, did not stir, although it is to be presumed she knew the facts of the case as well as other people. What a rotten farce this monarchical system is! ___

Pall Mall Gazette (24 March, 1892) “THE CULT OF THE SACRED BIRDS.” To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—The temptation to steal pheasants may be greater than the temptation to steal silver spoons, but if it be advisable in the interest of the public generally to preserve a certain number of game birds, which I venture to think Mr. Longman’s letter clearly proves, does it not then become necessary to inflict a more severe punishment than usual upon such persons as do not share that opinion, but maintain their right to pursue a course of conduct which, if allowed to continue, would exterminate game altogether? I am not well acquainted with the purely agricultural districts, and it may be that the poacher such as Kingsley described still exists in such districts; but certainly in the manufacturing counties of the North poaching has become a purely commercial pursuit. Pheasants are poached for the market; rabbits are often taken alive in large quantities for the purpose of providing the miners with a day’s “play” in the shape of rabbit-coursing. The assize calendars show, moreover, that poaching is closely allied to fowl-stealing. In poaching cases there is nearly always a previous conviction for robbing a hen-roost; and, vice versá, the chicken-stealer is often a poacher by profession.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant, _____

DEAR SIR,—With reference to Mr. Auberon Herbert’s fantastic deliverances on the recent poaching affray and its fatal results, may I bring it to your notice that Schopenhauer, who was, like Mr. Herbert, an extreme individualist and advocate of administrative Nihilism, was not, nevertheless, so swayed by his prepossessions as to lose sight of the significant fact that popular feeling does not accept the buckram attitude of' the lawyers in respect to rights of property in game? In the third volume of his magnum opus Schopenhauer quotes with approval the ex-President Quincy Adams’s argument against Indian rights of possession to the forest he ranges in quest of prey, and goes on to remark that, while the law punishes poaching just as severely as theft, and in many countries more severely, yet civil honour, though irrevocably lost by the latter, is by the former really not affected. For, says the philosopher, the principles of civil honour rest upon moral law, not upon mere positive enactment; but game is not an object upon which labour is bestowed, and is thus not an object of a morally valid possession. Considering how the father of modern pessimism hated Socialism and all its works, it is much to his credit that he saw so clearly and stated so frankly this case of antagonism between statute and popular opinion, and yet was not led by his individualist views to bless the former. Who, then, will not smile to find that Mr. Herbert, the refined Atticus, who insists on “grace” as opposed to “law,” and contemns legal incumbrances for restraining the free play of individual development, comes forward as apologist for the law in a case where its strict exercise is repugnant to the feelings of the ordinary man?When will Mr. Herbert learn that property was made for man and not man for property, and cease on its behalf to profane the sacred name of liberty?—Faithfully yours, _____

SIR,—As a shooter of no small experience allow me to say how greatly I admire your views regarding the butchery of pheasants. If you have never seen a large battue for pheasants allow me to describe one to you. For weeks beforehand the birds are fed in an enclosure surrounded by wire 6 feet high, and covered in with netting at the top! This is done to cause the game to become tame. Early on the day of the shooting about half the birds are caught by keepers with hand-nets, and their wings, or rather one wing of each, is slightly clipped; this prevents the birds from flying too fast for the shooters. Many of the birds have both wings clipped, so that they may be killed on the ground by the beaters with sticks to make, sure of a grand total atthe endof the day in case the shooters are bad shots.Now, imagine eight to twelve, or even fifteen, gentlemen, each with three guns and three loaders, standing close round the end of a wood with these partially crippled pheasants (encompassed as they are by men and nets) all huddled together just before the guns! Of course some of the birds can fly, and these are as often missed as killed—oftener, a good deal; but the wing-clipped ones, as they are driven forward by the keepers in a drove like sheep, are either shot down at six or seven yards’ distance as they spring off the ground in their endeavours to fly, or are else shot as they run along the ground!—a truly sporting sight! The headkeepersoon appears and says, “Good sport, I hope, gentlemen,” and is told, “Splendid, excellent; we never saw so many or such fine birds.” When several woods are shot through in this fashion luncheon takes place. Whilst luncheon (soup, fish, joints, &c., washed down by champagne, with music at times as a variety) progresses a very curious scene is enacted just out of sight, and this is the advent of the local auctioneer, who knocks down the game to various dealers at so much a brace according to the bidding! At the close of the day a similar scene occurs, and the auctioneer (who is sometimes given the use of a gun and dog) finally hands a handsome cheque to the lord of the manor for the game he has sold!

(Mr. Rodwell, the Postmaster of Tring, requests us to acknowledge the receipt of £2 from “P.M.” towards the fund for the Relief of the Families left destitute by the Pitstone Poaching Case.) ___

Pall Mall Gazette (26 March, 1892) THE LATE DUKE OF BEDFORD. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—My attention has been called to a letter in your issue of the 19th inst. signed “Robert Buchanan,” in which it is stated that the late Duke of Bedford, on account of a dispute over the price at which his game should be sold, held a great battue at which over a thousand birds were killed; that he then caused them to be buried, and watched till they rotted in the ground. _____

To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—I have been enabled, through your courtesy, to see a proof of the letter from Sir Edward Malet to be published in your columns. Before I make any comment upon the disclaimers in that letter, it is necessary for me to communicate with the persons who furnished me with the particulars which I published. May I add, in the meantime, that no one will be more delighted than myself if I have been misinformed? But in one particular, I think, Sir Edward Malet must be in error. If the late Duke of Bedford did not preserve “game,” under what designation may we describe the innumerable tame birds reared on his estates at Woburn Park? and to what category did the men in the Duke’s service who guarded these preserves properly belong? I have been hitherto under the impression that the tame birds were “pheasants,” and that the men in the Duke’s service were “gamekeepers.” I shall be able, in a few days, to explain my statement fully, if not to withdraw it absolutely.—I am, &c., ___

The Bucks Herald (26 March, 1892 - p.2) (From “FIGARO.”) There may be room for difference of opinion as to whether the Buckinghamshire poachers should have been hanged last week, but there is no room for difference of opinion concerning the rant in which Mr. Robert Buchanan has indulged on the subject. Not content with accusing Mr. Justice Lawrance of strong animus against the murderers, the jury of cowardice, and the Home Secretary of injustice and inhumanity, Mr. Buchanan has endeavoured to prove that, as the Royal prerogative of mercy was not exercised in this case, the Queen of England had better be abolished. This leads me to suggest that, in the event of a vacancy, Mr. Buchanan—is there a Mrs. Buchanan?—should be installed as Sovereign, with supreme power to change Ministers as often as he pleases, and to take what steps he may consider necessary to purify society and remove the “bloodstains on our so-called Christian civilization.” ___

The Entr’acte (26 March, 1892 - p.4) What impudence to ask Mr. Robert Buchanan to support Mr. Berry, the late executioner! Mr. Buchanan joining hands with the hangman would have made a fitting climax to the series of humorous pictures now on view at the Aquarium. But why does Mr. Berry want to lecture on the desirability of abolishing capital punishment? It isn’t because he is not destined to make any more money out of it, I suppose? If Mr. Berry be of opinion that punishment by death is unrighteous, how long has he been of this way of thinking? He could hardly have held such views when he was, of his own free will, dealing out death to criminals as often as a job was given him to do; or if he did, how he must have suffered! I have not the smallest wish to do an injustice to Mr. Berry, but neither do I feel any great interest in the man; though I should rather like to be informed as to the cause of Mr. Berry’s conversion, for I presume that a hangman does not relinquish neck-breaking and inveigh against its unrighteousness, without good reason. I should be glad to learn definitely whether Mr. Berry resigned his appointment, or if he had to succumb to that process which is sometimes called the “push.” I am also of opinion that the man who has been employed as hangman by the State should not be permitted to make capital out of his office. I have not heard Mr. Berry lecture, nor do I think it at all likely that I shall have this honour; therefore I am in ignorance of the manner in which he treats his subject; but if his expressions of opinion be backed by the recital of events that have occurred in the executioner’s room, then I happen to believe that such a scheme should be directly vetoed. At any rate, I hope that this type of so-called entertainment will not extend to our variety establishments, and that our eyes are not to be regaled by the sight of an advertisement informing us that Mr. Berry is “doing three turns nightly at the principal London halls.” ___

Pall Mall Gazette (28 March, 1892) THE GAME LAWS. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—So far as I am able to understand Mr. Auberon Herbert’s letter in your issue of to-day, he seems under the impression that game is property. May I point out that not even in English law (far less in Roman law, the fountain of all modern jurisprudence) are the wild fowl of heaven the property of any one? The sacred landlord has a right to the possession of the sacred birds so long as they are on his land, and this on account of the possession of the land; and possession, or the right to it, is no doubt a large item in the quality of property. But it is very far from being ownership, and even the right to possession, such as it is, vanishes altogether the moment the birds go on to another man’s land. The question of the recent legalized murders at Tring is purely an ethical one, and there is no need for mystifying it with hypothetical problems about dominium. _____

SIR,—The time has come for a forward movement by influential persons in the cause of those creatures which are for the ornament of our parks and protection of our crops from hosts of marauding insects which annually produce such ravages on them. Though by means of careful cultivation and artificial manures these pests are held in check, we are playing into the enemies’ hands by depriving ourselves of one of Nature’s remedies, in destroying the balance of Nature by the slaughter of game for the simple gratification of animal passions, shutting our eyes to the warning, “Woe unto those who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter,” and “meat for the belly and the belly for meat, but both shall perish with the using.” If a little self-denial were exercised by those who hold the power in their hands, as the influence of example of the classes would react on the masses, a strong association formed by the leading landowners in the country for the protection and perpetual preservation of game birds would go a long way in setting an example to smaller men; and the immunity of their crops from insect pests would prove that the Biblical story of the quails had in it a warning for other than the wandering Jew. Hoping this may meet the eye of some who look into the future, I am, Sir, yours, ___

[Note: The Watford Observer site has an article about ‘The Aldbury Murders’, which includes some information about Mrs. Humphry Ward’s connection to the case and her novel, Marcella.] _____

Letters to the Press - continued or back to the Letters to the Press menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|