ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Review of Swinburne’s Notes on Poems and Reviews. According to a letter to W. M. Rossetti of 12th November, Swinburne believed Buchanan to be the author of this review. Both Cassidy and Murray accept the attribution. However The Athenæum Index of Reviews and Reviewers: 1830-1870 assigns the authorship to Dr. John Doran.

The Athenæum (3 November, 1866 - No. 2036, p.564-565) Notes on Poems and Reviews. By Algernon Charles Swinburne. (Hotten.) Mr. Swinburne, with a reluctance which may be easily understood, heralds the new issue of his ‘Poems and Ballads’ by these Notes on his work and on what was said of it by his reviewers. He stoops, however, to the commonplace and vulgar affectation of scorning his critics. He cares as little for their praise as for their censure. He repudiates the idea of making any apology, vindication, answer, or appeal, and then proceeds to make what he repudiates. He might never have heard, he says, in a certain lofty way, of his adverse critics “but for their attacks.” This is exactly what is felt, if not said, by every offender, with respect to the unbiassed officials who calmly state their case against him, before the as calmly listening judge. ___

Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads. A Criticism by William Michael Rossetti Opening sentence of Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads. A Criticism by William Michael Rossetti (London: John Camden Hotten, 1866). |

|

|

‘Mr. Arnold’s New Poems’ by Algernon Charles Swinburne Buchanan would later call this mention of David Gray in Swinburne’s article as ‘the fons et origo of the whole affair’. Although Buchanan confuses this with the later footnote on Gray which Swinburne added to the article when it was published in Essays and Studies (London: Chatto & Windus, 1875), his article on ‘George Heath, The Moorland Poet’ published in Good Words in March 1871, includes this footnote: ‘Mr. Algernon Charles Swinburne, author of “Atalanta in Calydon,” went some years ago far out of his way to call David Gray a “dumb poet”—meaning by that a person with great poetical feeling, but no adequate powers of expression. So many excellent critics have resented both this impertinence and the unfeeling language in which it was expressed, that Mr. Swinburne is doubtless ashamed enough of his words by this time; but would it not have been as well if, before vilifying a dead man, he had first read his works, which, if they possess any characteristic whatever, are noticeable for crystalline perfection of poetic form, unparalleled felicity of epithet (witness the one word “sov’reign” as applied to the cry of the cuckoo), and emotion always expressed in simple music? When Mr. Swinburne and the school he follows are consigned to the limbo of affettuosos, David Gray’s dying sonnets will be part of the literature of humanity.’

The Fortnightly Review (October, 1867 - Vol. 8, p. 428) |

|

|

This review of Swinburne’s essay on Matthew Arnold is believed by Murray to have been written by Buchanan (he cites Clyde Kenneth Hyder’s Swinburne’s Literary Career and Fame and Swinburne Replies as supporting this view). Murray also quotes part of a letter from Swinburne to W. M. Rossetti, written on 11th October, referring to Henry Kingsley: “He is also excited about the very gross insolence and scurrility of the Spectator and we both think the polecat’s nest wants smoking out. For Urizen’s sake—or rather Orc’s—hasten the Whitman work if you can—for I see advertsied in a thing called the ‘Broadway’—this! ‘Walt Whitman: by Robert Buchanan;’ the word ‘polecat’ reminded me.”

The Spectator (5 October, 1867 - pp. 9-11) MR. SWINBURNE AS CRITIC. IN a recent article, in many respects of no common merit, on Mr. Swinburne’s poetry, and one, like almost all those which have hitherto appeared in our contemporary the Chronicle, marked by an intellectual care, thoroughness, and precision of thought which make its pages far more instructive than those of almost any weekly journal of the day, the reviewer asserts that Mr. Swinburne’s poetry, with all its “wealth of lyrical sweetness,” is marked by “barren poverty of thought.” There is truth in this; there is no intellectual thread in any single poem of his that we can remember; and in his last, on Italy, where there was most need of intellectual study, the trace of an intellect vanished altogether. But though Mr. Swinburne has never shown the least intellectual sympathy even with the most characteristic currents of thought in his own favourite Greece, he has the natural delight of true poetic genius in the greater poets of every age, and whatever intellectual discrimination he has, has been exercised in studying the individual characteristics of his favourite singers. In the new number of the Fortnightly Review he measures himself with. great boldness against the most accomplished critic of the day, Mr. Matthew Arnold, and scatters over a review of that fine poet many brilliant remarks on English and French poets which show that he has studied them deeply, and that he has often caught accurately, and when he has caught accurately can delineate with unequalled power, their finest individual traits. But in spite of a much greater wealth of critical perception than we might have expected from him, in spite of many fine and some splendid sayings, in spite of an obviously great effort at the tranquillity and calm of his model for the time being,—Mr. Arnold,—we doubt if Mr. Swinburne ever placed himself to greater disadvantage than in the position of critic to that thoughtful and equal-minded poet. It is not that he makes very many false criticisms on his special subject,—most of them are true, and many brilliantly expressed,—but that while his critical eye is often true, he never for a moment falls into the mood of true criticism, the mood in which you feel that the critic is surrendering himself, so far as he can without unfaithfulness to his own inner judgment, to the overruling control of another’s imagination or thought. There is barely a single sentence written in this mood through the entire article. When Mr. Swinburne praises, which he often does with great force, you feel that he is trying to cap the quality he is praising by the brilliance of the language in which he describes it. Never for a complete sentence, seldom for half a sentence, do you lose the excitable personality of the critic. Like a humming-bird, he dashes about among the blossoms of the author whom he panegyrizes, vying with them in colour, and restlessly displaying his own wonderful activity as well. There is, too, an odious strut in his style which will seldom let you forget the vanity of his brilliant sayings in their truth and aptness. If he rises into eloquence, as he often does, he is not content till he rises out of it again into that harsh, shrill, peculiar note,—like the peacock’s dissonant cry,—which drowns the note proper to his subject, and racks the ear with its discord. The essay abounds in happy sayings, spoiled by this dissonant and impatient treble, in which you seem to hear Mr. Swinburne’s feverish desire to surpass the excellences he criticizes. This, at the best, is not criticism, for you are never for a moment left with your “eye simply on the object.” Directly the critic’s eye rests for an instant on his object, he sets to work to bring such a battery of fireworks to play on the point in question, that he and everybody else thinks a great deal more of the iridescent lights than of the thing illuminated. If he cannot succeed, as he often can, in getting up a much more exciting display on the outside of the show by his description, than those who go in to look at it themselves will find, he goes out of the way to say something irrelevant in a note, the only function of which is to startle or challenge. A more successful intellectual irritant than Mr. Swinburne’s criticisms we do not ever remember to have met with. When we agree with him most entirely, and admire his unwonted power of expression most deeply, we are perhaps even more chafed by his shrill falsetto climax than we are when he tauntingly drags us aside into the private audience of a note, only in order to stick a pin into us. Nothing could be finer or truer, for instance, than this on Wordsworth:— His concentration, his majesty, his pathos have no parallel; some have gone higher, many lower, none have touched precisely the same point as he; some poets have had more of all these qualities, and better; none have had exactly his gift. His pathos, for instance, cannot be matched against any other man’s; it is trenchant, and not tender; it is an iron pathos. Take, for example, the most passionate of his poems, the “Affliction of Margaret;” it is hard and fiery, dry and persistent as the agony of a lonely and a common soul which endures through life a suffering which runs always in one groove, without relief or shift. Because he is dull, and dry, and hard, when set by the side of a great lyrist or dramatist; because of these faults and defects, he is so intense and irresistible when his iron hand has hold of some chord which it knows how to play upon. How utterly unlike his is the pathos of Homer or Æschylus, Chaucer or Dante, Shakespeare or Hugo; all these greater poets feel the moisture and flame of the fever and the tears they paint; their pathos when sharpest is full of sensitive life, of subtle tenderness, of playing pulses and melting colours; his has but the downright and trenchant weight of swinging steel; he strikes like the German headsman, one stroke of a loaded sword. Yet while we admire, we chafe at the various turns in the sentence, which show you how little the critic is thinking of Wordsworth as he writes, how much of his own fine scales for weighing Wordsworth. “The downright and trenchant weight of swinging steel,” the “German headsman’s one stroke of a loaded sword,” are ornamental sentences as far as possible from the tone of Wordsworth,—mere efforts to bring the critic forward again after his true and fine previous description of Wordsworth’s pathos. When he had said of “The Affliction of Margaret” that it is “hard and fiery, dry and persistent, as the agony of a lonely and a common soul, which endures, through life, a suffering which runs always in one groove, without relief or shift,”—he had described with unequalled power the drift of such lines as,— My apprehensions come in crowds, —but he cannot rest there. His critical mood is feverish and restless till he has eclipsed the object of his vision by some of his own feats of language, and so he gets into his “swinging steel” and “one stroke of a loaded sword,” which are about as inexpressive of that strange possession by the genius of common but ineffaceable and undiminishable misery, which enabled Wordsworth to write as he did, as any form of words that could be invented. The “stroke of swinging steel” expresses force and momentum of will, not that truthfulness which comes from the singleness of a haunted and overridden imagination. This figure is a rhetorical flourish of Mr. Swinburne’s sword, not of Wordsworth’s, and, instead of clinching the thought, cleaves it in two, and makes you stare up at the brandishing hand which you had barely for a moment forgotten. The supreme charm of Mr. Arnold’s work is a sense of right resulting in a spontaneous temperance which bears no mark of curb or snaffle, but obeys the hand with imperceptible submission and gracious reserve. Other and older poets are to the full as vivid, as incisive and impressive; others have a more pungent colour, a more trenchant outline; others as deep knowledge and as fervid enjoyment of natural things. But no one has in like measure that tender and final quality of touch which tempers the excessive light and suffuses the refluent shade; which as it were washes with soft air the sides of the earth, steeps with dew of quiet and dyes with colours of repose the ambient ardour of noon, the fiery affluence of evening. Down to “refluent shade” we are simply delighted with so artistic a delineation of Mr. Arnold’s style, but then we get to a rush of adjectives which have the effect of entirely drowning Mr. Arnold, and making us hold our breath at the lavish wealth of language of his gorgeous critic. “Ambient ardour of noon” and “fiery affluence of evening” seem expressly intended to extinguish the remembrance of Mr. Arnold’s delicate and temperate touch. Mr. Swinburne cannot bear to rest in the cool shower of Mr. Arnold’s placid truthfulness; he feels that he must blaze out upon it like the sun, and light up in it the many-coloured bow of his own more splendid genius. I take leave to forge this word, because “self-sufficingness” is a compound of too barbaric sound, and “self-sufficiency” has fallen into a form of reproach. Archbishop Trench has pointed out how and why a word which to the ancient Greek signified a noble virtue came to signify to the modern Christian the base vice of presumption. I do not see that human language has gained by this change of meaning, or that the later mood of mind which dictated this debasement of the word is at all in advance of the older, or indicative of any spiritual improvement; rather the alteration seems to me a loss and discredit, and the tone of thought which made the quality venerable more sound and wise than that which declares it vile. This is rather like a schoolboy’s irreverent taste for making impertinent signs at the authorities of his home or school. It has nothing to do with the drift of the criticism, and as Mr. Swinburne has never shown the slightest sign of spiritual insight into either Christian ideas, or Christian ethics, or Christian sentiment, as there is no vestige of his ever having passed through even a phase of temporary sympathy with the highest literature of the last eighteen centuries, this childish little gesture of irrelevant pertness can derive not the slightest force from his unquestionable genius. The whole article is marred and spotted by this restless vanity, which is always driving Mr. Swinburne into little digressions of moral grimace. What, for example, should have induced him, by way of illustrating Mr. Arnold’s happy executive skill as a poet, to go off into the following digression on the theory of ‘dumb poets’ and ‘handless painters,’ unless it be the pleasure of the sneer at an exquisite poet who died in his youth, with which it is illustrated? It is as foreign to the subject of the article as a fly to the amber in which it is preserved, and a very nasty fly in amber it seems to us:— There is no such thing as a dumb poet or a handless painter. The essence of an artist is that he should be articulate. It is the mere impudence of weakness to arrogate the name of poet or painter with no other claim than a susceptible and impressible sense of outward or inward beauty, producing an impotent desire to paint or sing. The poets that are made by nature are not many; and whatever “vision” an aspirant may possess, he has not the “divine faculty” if he cannot use his vision to any poetic purpose. There is no cant more pernicious to such as these, more wearisome to all other men, than that which asserts the reverse. It is a drug which weakens the feeble and intoxicates the drunken; which makes those swagger who have not learnt to walk, and teach who have not been taught to learn. Such talk as this of Wordsworth’s is the poison of poor souls like David Gray. Men listen, and depart with the belief that they have this faculty or this vision which alone, they are told, makes the poet; and once imbued with that belief, soon pass or slide from the inarticulate to the articulate stage of debility and disease. Inspiration foiled and impotent is a piteous thing enough, but friends and teachers of this sort make it ridiculous as well. A man can no more win a place among poets by dreaming of it or lusting after it than he can win by dream or desire a woman’s beauty or a king’s command; and those encourage him to fill his belly with the east wind who feign to accept the will for the deed, and treat inarticulate or inadequate pretenders as actual associates in art. The Muses can bear children and Apollo can give crowns to those only who are able to win the crown and beget the child; but in the school of theoretic sentiment it is apparently believed that this can be done by wishing. We are inclined to accept (with some wonder, and a good deal of allowance for the spirit of opposition which breathes in Mr. Swinburne’s panegyrics on poets of no name) our critic’s positive insights,—though he does overdo his ecstasies, as, for instance, concerning Miss Christina Rossetti, who, it appears, could, with any one verse or word, “absorb and consume” Eugenie de Guérin, “as a sunbeam of the fiery heaven, a dew drop of the dawning earth.” We are disposed to think sincerely that the fault must be in ourselves, if we have read with faint interest and no admiration poems in which Mr. Swinburne can feel so much delight as he certainly does in a hymn of Miss Rossetti’s. But we do not feel the slightest respect for his incidental sneers, like that at David Gray. There are several of David Gray’s sonnets which, with all our reverence for Mr. Arnold, seem to us far above any of Mr. Arnold’s sonnets, except the one great sonnet on Sophocles. Many of David Gray’s, —for example, the one ending, I weigh the loaded hours till life is bare, will live as long as English literature. In fact, so far from being a dumb poet, David Gray’s powers of sweet, clear, low music of language have rarely been equalled. Nothing shows us how Mr. Swinburne’s fine critical aperçus are prevented from developing into anything like a fair, tranquil, critical insight, more than these horrid blotches, needlessly and disastrously spotted over his essay, apparently for mere caprice or pique. ___

Introduction to David Gray and other Essays, chiefly on poetry

FIRST WORD. IT is from no desire to appear in a new character that I publish the present volume. The following Essays, indeed, are prose additions and notes to my publications in verse, rather than mere attempts at general criticism, for which, indeed, I have little aptitude. They are my Confession of Faith. I have here briefly touched on several great and magnificent questions immediately affecting the poetic personality:—on the nature and character of the Poet par excellence, on the Student’s Vocation, on what is and what is not moral in the Student’s Utterance, slightly on religious light and truth; illustrating my matter by such sketches as that of Whitman, and such notes as that on Herrick’s Hesperides. More would have been added, and particularly an Essay on “The Poetry of David Gray,” had not my health suddenly broken down just as the volume was going to press. The book, however, is complete as it stands,—an epitome of what may be said hereafter in different ways. ROBERT BUCHANAN. ___

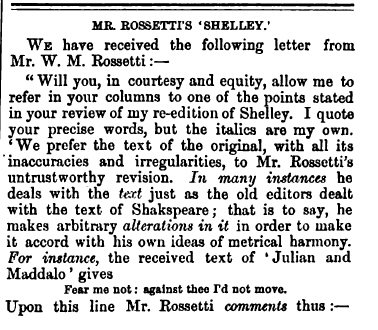

Athenæum review of W. M. Rossetti’s edition of Shelley Both Cassidy and Murray attribute this review of William Michael Rossetti’s The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley to Buchanan. However The Athenæum Index of Reviews and Reviewers: 1830-1870 assigns the authorship to Thomas Watson Jackson.

The Athenæum (29 January, 1870 - No. 2205, p. 154-156) |

|

|

|

|||

|

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Click the pictures for readable versions.

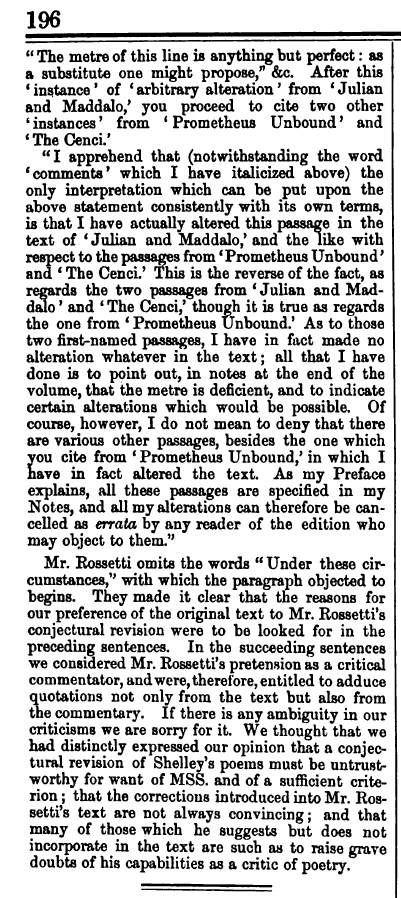

The Athenæum (5 February, 1870 - No. 2206, p. 195-196) |

|

|||

|

|||

|

The Brothers by Dante Gabriel Rossetti This poem was included in the unpublished pamphlet version of Rossetti’s reply to Buchanan’s ‘Fleshly School’ article, ‘The Stealthy School of Criticism’. A revised version of the poem was included in the 1911 edition of The Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. THE BROTHERS. I AM two brothers with one face, Here are some poets and they sell, My books aren’t bought; it’s a burning shame, So at least all other bards I’ll slate I took a beast of a poet’s tome And after supper, in lieu of bed, Of eyelids kissed and all the rest, I told the worst that pen can tell,— I crowed out loud in the silent night, In our Contemptible Review I tanned his hide and combed his head And now he’s wrapped in a printer’s sheet,

Later version from The Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1911) p. 276:

THE BROTHERS:

I AM two brothers with one face, Of course you know it’s a burning shame, I took a beast of a poet’s tome Of eyelids kissed and all the rest, I crowed out loud in the silent night, I tanned his hide and combed his head, ___

‘Among the Books of Seventy-one’ in Temple Bar Not all of the responses to Buchanan’s ‘Fleshly School’ article were hostile.

Temple Bar (December, 1871) From ‘Among the Books of Seventy-one, by a Reader,’ (Vol. 34, pp. 97-112) pp. 98-100 Every regiment marches with its band first. Let us begin with our musicians, the poets. “I, too, that have not tongue nor knee “It was for this, that prayers like these “It was for this, that men should make What is the use of reminding a poet who writes thus recklessly that the world is growing steadily, if slowly, better?— that year by year men become more free; kings lose every year something of their power; priests every year concede, bon gré mal gré, something of their pretensions, and life does really become to the world at large brighter, better, and more healthy? But no; he will see nothing of all this. “Come down,” he shrieks, regardless of the infinite pain his words may give to others— “Come down: be done with: cease: give o’er: The words are so intense that we doubt the genuineness of their feeling. The argument is so weak that the conclusion shows like a shriek of hatred. If Christianity has no more mighty assailant than Mr. Swinburne, her reign will be long indeed. “The dumb dread people, that sat Mr. Swinburne wants a faith—a faith in the commonest nostrum would be something—to give him ballast. The vagueness of his verse comes from a sheer inability to define his aspirations. Even his erotic verse, warm enough in all conscience, wants reality. There is the delirium of passion, exaggeration of the maddest desire; but where is the reverence, where the reticence of true love? The poet does not know love, any more than he knows the Christianity at which he shrieks, or the pretended sufferings of the people which he attempts to sing. _____

|

|

|

|

|

|

|