|

THE FLESHLY SCHOOL CONTROVERSY

Other Accounts of the Fleshly School Controversy - 3

From In Good Company by Coulson Kernahan

(London: John Lane, 1917.)

pp.111-125

ONE ASPECT OF THE MANY-SIDEDNESS OF

THEODORE WATTS-DUNTON

I HAVE often been asked by those who did not know Theodore Watts-Dunton what was the secret of the singular power he appeared to exercise over others and the equally singular affection in which he was held by his friends.

My answer was that Watts-Dunton’s hold upon his friends, partly personal as it was and partly intellectual, was chiefly due to his extraordinary loyalty. Of old, certain men and women were supposed to be possessed of the “evil eye.” Upon whom they looked with intent—be it man, woman, or beast—hurt was sooner or later sure to fall.

If there be anything in the superstition, one might almost believe that its opposite was true of Watts-Dunton. He looked upon others merely to befriend, and if he did not put upon them the spell, not of an evil but of a good eye, he exercised a marvellous personal power, not, as is generally the case, upon weaker intellects and less marked personalities than his own, but upon his peers; and even upon those whom in the world’s eye would be accounted greater than he. That any one man should so completely control, and even dominate, two such intellects as Swinburne and Rossetti seemed almost uncanny. I never saw Rossetti and Watts-Dunton together, 112 for the former had been dead some years when I first met Watts-Dunton, but my early literary friendships were with members of the little circle of which Rossetti was the centre, and all agree in their testimony to the extraordinary personal power which Watts-Dunton exercised over the poet-painter. But Swinburne—and here I speak with knowledge—Watts-Dunton absolutely dominated. It was, “What does Walter say about it?” “Walter thinks, and I agree with him, that I ought to do so and so,” or, “Let us submit the matter to Watts-Dunton’s unfailing judgment.”

Here, for fear of a possible misunderstanding, let me say that, if any reader assume from what I have just written that Swinburne was something of a weakling, that reader is very much mistaken. It is true that the author of Atalanta in Calydon was a greater force in intellect and in imagination than in will power and character, but he was not in the habit of deferring to others as he deferred to Watts-Dunton, and when he chose to stand out upon some point, or in some opinion, he was very difficult to move. It was only, in fact, by Watts-Dunton that he was entirely manageable, yet there was never any effort, never even any intention on Watts-Dunton’s part to impose his own will upon his friend. I have heard his influence upon Swinburne described as hypnotic. From that point of view I entirely dissent. Watts-Dunton held his friends by virtue of his genius for friendship—“Watts is a hero of friendship,” Mr. William Michael Rossetti once said of him—and by the passionate personal loyalty of which I have never known the equal. By nature 113 the kindest of men, shrinking from giving pain to any living creature, he could be fierce, even ferocious, to those who assailed his friends. It was, indeed, always in defence of his friends, rarely if ever in defence of himself—though he was abnormally sensitive to adverse criticism—that he entered into a quarrel and, since dead friends could not defend themselves, he constituted himself the champion of their memory or of their reputation, and even steeled himself on more than one occasion to a break with a living friend rather than endure a slight to one who was gone. “To my sorrow,” he writes in a letter, “I was driven to quarrel with a man I loved and who loved me, William Minto, because he, with no ill intentions, printed certain injurious comments upon Rossetti which he found in Bell Scott’s papers.”

It was my own misfortune, deservedly or undeservedly, to have a somewhat similar experience to that of Professor Minto; but in my case the estrangement, temporary only as it was, included Swinburne as well as Watts-Dunton. In telling the story, and for the first time here, I must not be supposed for one moment to imagine that any importance attaches or could attach to a misunderstanding between such men as Swinburne and Watts-Dunton and a scribbler of sorts like myself, but because a third great name, that of Robert Buchanan, comes into it.

It is concerned with Buchanan's attack upon Rossetti in the famous article The Fleshly School of Poetry, which appeared anonymously (worse pseudonymously) in the Contemporary Review. Not 114 long after Buchanan’s death I was asked to review Mr. Henry Murray’s Robert Buchanan and other Essays in a critical journal, which I did, and Swinburne and Watts-Dunton chanced to see the article. To say that they took exception to what I said about Buchanan, would be no description of their attitude, for Swinburne not only took exception but took offence and of the direst—so much so as to make it necessary that for a season I should discontinue my visits to The Pines.

And here let me interpolate that I entirely agree with Mr. James Douglas when he says in his volume, Theodore Watts, Poet, Novelist and Critic, “It would be worse than idle to enter at this time of the day upon the painful subject of the Buchanan affair. Indeed, I have often thought it is a great pity that it is not allowed to die out.” But when in the next sentence Mr. Douglas goes on to say, “The only reason why it is still kept alive seems to be that, without discussing it, it is impossible fully to understand Rossetti’s nervous illness about which so much has been said,” I am entirely out of agreement with him, as the quotation which I make from my article will show. Since Mr. Douglas has reopened the matter—he could hardly do otherwise in telling the story of Watts-Dunton’s literary life—I have the less hesitation in reprinting part of the article in which I endeavoured to clear Buchanan of what I held, and still hold, to be a preposterous charge. I may add that I quite agree with Mr. Douglas when he says that we must remember “the extremely close intimacy which existed between these two poet friends (Rossetti and Watts-Dunton) 115 in order to be able to forgive entirely the unexampled scourging of Buchanan in the following sonnet, if, as some writers think, Buchanan was meant.”

Mr. Douglas then quotes the sonnet The Octopus of the Golden Isles, which I do not propose here to reprint. That Buchanan was meant is now well known, and in fact Mr. Douglas himself says in the same chapter that Watts-Dunton’s definition of envy as the “literary leprosy” has often been quoted in reference to the case of Buchanan. My article on Buchanan is too long to give in its entirety, and, even omitting the passages with no direct bearing upon the misunderstanding which it caused, is lengthier than I could wish. My apology is, first, that in justice to Watts-Dunton and to Swinburne I must present their case against me ungarbled. Moreover, as the foolish bogey-story—like an unquiet ghost which still walks the world unlaid—that Buchanan was the cause of Rossetti taking to drugs, the cause even of Rossetti’s death, is still repeated, and sometimes believed, I am not sorry of another and last attempt to give the bogey its quietus. Here are the extracts from my article:

“Mr. Murray quotes evidently with appreciation Buchanan’s tribute to his ancient enemy Rossetti, I do not share Mr. Murray’s appreciation, for Buchanan’s tribute has always seemed to me more creditable to his generosity than to his judgment. He speaks of Rossetti as ‘in many respects the least carnal and most religious of modern poets.’

“Here he goes to as great an extreme as when he so 116 savagely attacked Rossetti as ‘fleshly.’ About this attack much nonsense has been written. We have been told that it was the cause of Rossetti’s taking to chloral; and I have heard even Rossetti’s death laid at Buchanan’s door. To my thinking talk of that sort is sheer nonsense. If Rossetti took to chloral because Buchanan called his poetry ‘fleshly,’ Rossetti would sooner or later have taken to chloral, had Buchanan’s article never been written. But when Buchanan in the fulness of his remorse calls Rossetti ‘the most religious of modern poets’ he is talking equally foolishly.

“Rossetti ‘the most religious of modern poets’! Why, Rossetti’s religion was his art. To him art was in and of herself pure, sacred, and inviolate. By him the usual order of things was reversed. It was religion which was the handmaid, art the mistress, and in fact it was only in so far as religion appealed to his artistic instincts that Rossetti can be said to have had any religion at all.

“And when Buchanan sought to exalt Rossetti to a pinnacle of purity he was guilty of a like extravagance. That Rossetti’s work is always healthy not even his most enthusiastic admirers could contend. Super-sensuous and southern in the warmth of colouring nearly all his poems are. Some of them are heavy with the overpowering sweetness as of many hyacinths. The atmosphere is like that of a hothouse in which, amid all the odorous deliciousness, we gasp for a breath of the outer air again. There are passages in his work which remind us far more of the pagan temple than of the Christian cloister, passages describing sacred rites which pertain not to the worship of the Virgin, but to the worship of Venus.

“Buchanan was a man who lived heart and soul in 117 the mood of the moment. He had a big brain which was quick to take fire, and at such times, both in his controversies and in his criticism, he was apt to express himself with an exaggeration at which in his cooler hours he would have been the first to hurl his Titanic ridicule.

“It may seem ungenerous to say so, but even his beautiful dedicatory poem to Rossetti strikes me as a lapse into false sentiment.

To An Old Enemy

I would have snatched a bay-leaf from thy brow,

Wronging the chaplet on an honoured head;

In peace and tenderness I bring thee now

A lily-flower instead.

Pure as thy purpose, blameless as thy song,

Sweet as thy spirit may this offering be;

Forget the bitter blame that did thee wrong,

And take the gift from me.

“After Rossetti’s death, ten months later, Buchanan added the following lines:

Calmly, thy royal robe of Death around thee,

Thou sleepest, and weeping brethren round thee stand;

Gently they placed, ere yet God’s angel crowned thee,

My lily in thy hand.

I never saw thee living, oh, my brother,

But on thy breast my lily of love now lies,

And by that token we shall know each other,

When God’s voice saith ‘Arise!’

“That this is very beautiful every one will admit, but is it true to picture those who most loved Rossetti as placing Buchanan’s lily of song in his dead hand? I think not. Nor can those who know anything of the last days of Rossetti reconcile the facts 118 with Buchanan’s imaginary picture of a sort of celestial assignation in which, by means of a lily, Rossetti and his ancient enemy and brother poet shall identify each other on the Last Day?

“I am well aware that I shall be accused of bad taste, even of brutality, in saying this; but, as Mr. Murray himself alludes to this ancient quarrel, I must protest that false sentiment is equally abhorrent—as Buchanan would have been the first to admit. Now that Buchanan has followed Rossetti where all enmities are at an end, it is right that the truth about the matter be spoken, and this unhappy assault and its not altogether happy sequel be alike forgotten.

“Robert Buchanan’s last resting-place is within sight of the sea. And rightly so. It is his own heart that Old Ocean seems most to wear away in his fretting and chafing, and the wearing away of their own heart is the most appreciable result of the warfare which such men as Buchanan wage against the world.

“That he did not fulfil his early promise, that he frittered away great gifts to little purpose, is pitifully true, but if he flung into the face of the men whom he counted hypocrites and charlatans, words which scorched like vitriol, he had, for the wounded in life’s battle, for the sinning, the suffering, and the defeated, words of helpful sympathy and an outstretched hand of practical help.

“Mr. Murray has shown Buchanan to us as he was; no hero perhaps, certainly not a saint, but a man of great heart and great brain, quick to quarrel, but as quick to own himself in the wrong; a man intensely, passionately human, with more than one man’s share of humanity’s weaknesses and of humanity’s strength, a sturdy soldier in the cause 119 of freedom, a fierce foe, a generous friend, and a poet who, in regard to that rarest of all gifts, ‘vision,’ had scarcely an equal among his contemporaries.

“I must conclude by a serious word with Mr. Murray. Disagree with him as one may and must, one cannot but admire his fearless honesty. None the less I am of opinion that in the following passage Mr. Murray’s own pessimism has led him to do his dead friend’s memory a grievous injustice.

“‘From the broken arc we may divine the perfect round, and it is my fixed belief that, had the subtle and cruel malady which struck him down but spared him for a little longer time, he would logically have completed the evolution of so many years, and have definitely proclaimed himself as an agnostic, perhaps even as an atheist.’

“Mr. Murray’s personal knowledge of Buchanan was intimate, even brotherly; mine, though dating many years back, was comparatively slight. But I have read Buchanan’s books, and I know something of the spirit in which he lived and worked, and I am convinced that Mr. Murray is wrong. It is not always those who have come nearest to the details of a man’s daily life, who have come nearest to him in spirit, as Amy Levy knew well when she wrote those lines, To a Dead Poet, which I shall be pardoned for bringing to my readers’ remembrance:

I knew not if to laugh or weep:

They sat and talked of you—

’Twas here he sat: ’twas this he said,

’Twas that he used to do.

‘Here is the book wherein he read,

The room wherein he dwelt ;

And he’ (they said) ‘was such a man,

Such things he thought and felt.’

I sat and sat, I did not stir; 120

They talked and talked away.

I was as mute as any stone,

I had no word to say.

They talked and talked; like to a stone

My heart grew in my breast—

I, who had never seen your face,

Perhaps I knew you best.

“Buchanan was, as every poet is, a creature of mood, and in certain black moods he expressed himself in language that was open to an atheistic interpretation. There were times when he was confronted by the fact that, to human seeming, iniquity prospered, righteousness went to the wall, and injustice, vast and cruel, seemed to rule the world. To the Christian belief that the Cross of Christ is the only key to the terrible problem of human suffering, Buchanan was unable to subscribe, and at times he was tempted to think that the Power at the head of things must be evil, not good. It seems to me that at such times he would cry out in soul-travail, ‘No! no! anything but that! If there be a God at all He must be good. Before I would do God the injustice of believing in an evil God, I would a thousand times sooner believe in no God at all!’ Then the mood passed; the man’s hope and belief in an unseen beneficent Power returned, but the sonnet in which he had given expression to that mood remained. And because the expression of that mood was permanent, Mr. Murray forgets that it was no more than the expression of a mood, and tells us that he believes, had Buchanan lived longer, he would have become an atheist.

“Again I say that I believe Mr. Murray to be wrong. Buchanan, like his own Wandering Jew, 121 trod many dark highways and byways of death, but he never remained—he never could have remained—in that Mortuary of the Soul, that cul-de-sac of Despair which we call Atheism.

. . . . . .

“This is not the place in which to say it, but perhaps my editor will allow me to add how keenly I felt, as I stood by the graveside of Robert Buchanan in that little God’s acre by the sea, the inadequacy of our Burial Service, beautiful as it is, in the case of one who did not profess the Christian faith. To me it seemed little less than a mockery to him who has gone, as well as a torture to those who remain, that words should be said over his dead body which, living, he would have repudiated.

“Over the body of one whose voice is silenced by death, we assert the truth of doctrines which living he had unhesitatingly rejected. It is as if we would, coward-like, claim in death what was denied us in life.

“In the case of a man whose beliefs were those of Robert Buchanan, how much more seemly it would be to lay him to rest with some such words as these:

“‘To the God from Whom he came, we commend this our friend and brother in humanity, trusting that what in life he has done amiss, may in death be forgotten and forgiven; that what in life he has done well, may in death be borne in remembrance. And so from out our human love, into the peace of the Divine love, we commend him, leaving him with the God from Whom, when we in our turn come to depart whither he has gone, we hope to receive like pardon, forgiveness and peace. In God’s hands, to God’s love and mercy, we leave him.’”

Re-reading this article many years after it was 122 written, I see nothing in it to which friendship or even affection for either Rossetti or Buchanan could reasonably object.

This was not the view taken by Swinburne and Watts-Dunton. It so happened that I encountered the latter in the Strand a morning or two later, and more in sadness than in anger he reproached me with “disloyalty to Gabriel, disloyalty to Algernon, and disloyalty to myself.”

I replied that touching Rossetti, as he did not happen to be the King, had never so much as heard of my small existence, nor had I ever set eyes upon him, to accuse me of disloyalty to him, to whom I owed no loyalty, struck me as a work of supererogation. And, as touching Swinburne and Watts-Dunton himself, honoured as I was by the high privilege of their friendship, I could not admit that that friendship committed me to a blind partisanship and to the identification of myself with their literary likings or dislikings or their personal quarrels.

My rejection of the penitential role, to say nothing of my refusing to take the matter seriously, seemed to surprise and to trouble Watts-Dunton. While protesting the regard of everyone at The Pines for me personally, he gave me to understand that Swinburne in particular was so wounded by my championship as he called it of Buchanan, that he would have some trouble in making my peace in that quarter, and even hinted that an arrangement, by which I was either to lunch or to dine at The Pines within the next few days, had better stand over.

123 Naturally I replied—I could hardly do otherwise, as I did not see my way without insincerity to express regret for what I had written about Buchanan, though I did express regret that it had given offence to Swinburne and himself—that that must be as he chose, and so we parted, sadly on my side if not on his; and I neither saw nor heard from anyone at The Pines for some little time after. Then one morning came the following letter:

MY DEAR KERNAHAN,

Don’t think any more of that unpleasant little affair. Of course neither Swinburne nor I expect our friends, however loyal, to take part in the literary quarrels that may be forced upon us. But this man had the character among men who knew him well of being the most thorough sweep, and to us it did seem queer to see your honoured name associated with such a man. But, after all, even he may not have been as black as his acquaintances painted him. Your loyalty to us I do not doubt.

Yours affectionately,

THEODORE WATTS-DUNTON.

This was followed by a wire—from Swinburne—asking me to lunch, which I need hardly say I was glad to accept, and so my relationship to the inmates of The Pines returned to its old footing.

Since it was Swinburne much more than Watts-Dunton who so bitterly resented what I had written of Buchanan, I am glad to have upon my shelves a volume of Selections from Swinburne, published 124 after his death, and edited by Watts-Dunton. The book was sent to me by the Editor, and was inscribed:

“To Coulson Kernahan,

whom Swinburne dearly loved, and who

as dearly loved him.

From Theodore Watts-Dunton.”

My unhappy connection with the “Buchanan affair” had, it will be seen, passed entirely from Swinburne’s memory, and indeed the name of Robert Buchanan, who was something of a disturbing element even in death, as he had been in life, was never mentioned among us again. How entirely the, to me, distressing if brief rift in my friendship with Watts- Dunton— a friendship which I shall always count one of the dearest privileges of my life—was closed and forgotten, is clear from the following letter. It was written in reply to a telegram I sent, congratulating him on celebrating his 81st birthday—the last birthday on earth, alas, of one of the most generous and great-hearted of men:

THE PINES, PUTNEY, S.W.

Oct. 20th, 1913.

MY DEAR KERNAHAN,

Your telegram congratulating me upon having reached my 81st birthday affected me deeply. Ever since the beginning of our long intimacy I have had from you nothing but generosity and affection, almost unexampled, I think, between two literary 125 men. My one chagrin is that I can get only glimpses of you of the briefest kind. Your last visit here was indeed a red-letter day. Don’t forget when occasion offers to come and see us. Your welcome will be of the most heartfelt kind.

Most affectionately yours,

THEODORE WATTS-DUNTON

_____

From Swinburne's Literary Career and Fame by Clyde Kenneth Hyder

(1933, reissued 1963 - New York: Russell & Russell, Inc.)

pp. 171-181

Some tirades preceding the publication of Under the Microscope have now to be described. An article in The Edinburgh Review 86 for July, 1871, denounces Poems and Ballads with all the bitterness of the critics of 1866, and on the same grounds. Here are the old catchwords—blasphemy, glorification of sensuality, baseness, the proclaiming of principles subversive of domestic life, obscurity, reaction against all human and divine laws, lack of reserve. Among Swinburne’s mannerisms are named the abuse of antithesis, faulty rhymes, even harsh versification. When the critic says that Swinburne belongs to “what is known as the sensational school of literature,” and that his work derives from the corrupt French school of art and poetry, he is anticipating the chief ideas in Buchanan’s attack.

Passing over an essay by H. Buxton Forman, 87 also belonging to 1871, I shall discuss that notorious attack. Buchanan’s original article The Fleshly School of Poetry, as it appeared in The Contemporary Review 88 for October, 1871, is directed chiefly against Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Poems, 172 but Swinburne is censured for his “hysteric tone and overloaded style,” and for other qualities he is supposed to share with Rossetti. Poems and Ballads was more blasphemous than anything of Rossetti’s, yet Laus Veneris and Anactoria arouse comic amazement rather than more sinful emotions:

It was only a little mad boy letting off squibs. . . . “I will be naughty!” screamed the little boy; but, after all, what did it matter?

In the pamphlet entitled The Fleshly School of Poetry, and Other Phenomena of the Day, published in the spring of 1872, Buchanan devotes more attention to Swinburne. After a short harangue on the omnipresence of the Leg 89 (with a capital), which has even begun to serve as a model for different kinds of confectionery, Buchanan gives a fanciful history of English literature, attributing its darkness after Chaucer to Italian influence. “Scrofulous” influences culminated, he says, in France with Gautier and Baudelaire; the latter is the godfather of the modern “fleshly school.”

All that is worst in Mr. Swinburne belongs to Baudelaire. The offensive choice of subject, the obtrusion of unnatural passion, the blasphemy, the wretched animalism, are all taken intact out of the Fleurs de [sic] Mal.

Buchanan thinks that Swinburne acquired even the idea for his women from Baudelaire.

Accustomed to the Swinburnian female, we at once recognize her here in the original, as the serpent that dances, the cat that scratches and cries, and the large-limbed sterile creature who never conceives. . . . She is, in fact, Faustine, Mary Stuart, Our Lady of Pain, Sappho, and all the rest.

After Baudelaire’s death, Swinburne commemorated the event in some verses worthy of the French poet himself. In Songs before Sunrise there are signs that he has abandoned the Sapphic vein of Baudelaire, but his blasphemy has 173 become even more offensive. The poet is advised to burn his French books and seek other inspiration than “the smile of harlotry and the shriek of atheism.” So far he has offered only “borrowed rubbish.” Buchanan charges that Rossetti’s books have been reviewed by a coterie—an accusation to which Swinburne makes an indirect answer in his preface to Essays and Studies (1875). 90 Poems and Ballads does, of course, owe something to Baudelaire, but not nearly so much as Buchanan asserts 91 The criticism was well calculated to appeal to British insularity and to the prejudice against French literature.

The Fleshly School of Poetry leaves one with the impression that Buchanan was not only deficient in taste but also guilty of misrepresentation. In The Stealthy School of Criticism, and answer to the Contemporary Review article, Rossetti points out the way in which he distorts quotations. Nor was he disinterested, in spite of his statement that he had no grievance against Rossetti. In a letter written to Robert Browning in March, 1872, 92 Buchanan pleads guilty to “one instinct of recrimination,” referring to Swinburne’s unkind mention of David Gray. 93 The magazine article in which Swinburne alluded to that young poet was published in 1867. In 1866 Buchanan had written a savage review of Poems and Ballads for The Athenaeum and had lampooned Swinburne in The Spectator. What, then, becomes of the claim that “the first blow was struck by the other side?” 94 William Michael Rossetti had made slurring allusion to Buchanan in his defense of Swinburne, 95 it is true, but Buchanan had avenged himself adequately in his review of Rossetti’s edition of Shelley. 96

Buchanan was compromised by the circumstances attending the publication of his article in The Contemporary Review, which appeared with the signature “Thomas 174 Maitland.” The identity of the author was soon discovered. 97 On December 2, 1871, The Athenaeum announced that Sidney Colvin was preparing a reply to “Thomas Maitland,” a nom de plume for Robert Buchanan. A week later a letter from Colvin 98 denied that he was planning to answer “Mr. Maitland-Buchanan” but called attention to the latter’s naming himself among those mentioned for damaging comparison in The Fleshly School of Poetry, with the objects of his attack. In The Athenaeum for December 16 Buchanan acknowledged the authorship of the article and added that he had nothing to do with the signature, his own name being suppressed by an inadvertence, as his publisher could testify. Beneath his letter was printed a communication from Strahan and Company, publishers of The Contemporary Review, asserting that to attribute the article to Robert Buchanan was no more justifiable than to attribute it to Robert Browning, Robert Lytton, or any other Robert. On December 30 The Athenaeum published a letter from Buchanan referring to Alexander Strahan’s statement 99 that the publishers of The Contemporary Review were responsible for the pseudonym. Buchanan claimed that “Thomas Maitland” was affixed to the article when he was out of reach, “cruising on the shores of the western Hebrides.” In his preface to his pamphlet, however, he admitted that his essay had been signed “Thomas Maitland” “in order that the criticism might rest upon its own merits and gain nothing from the name of the real writer.” It is certain, as Miss Jay, Buchanan’s biographer, concedes, that Buchanan had no intention of attaching his name to the article.

Buchanan’s attack has become notorious chiefly because of its effect on Rossetti. Its censure of Swinburne was no harsher than that of dozens of other critiques which I have mentioned. The article did, however, popularize a phrase, 175 “the fleshly school,” and phrases are often more effective than ideas. Miss Jay 100 states that a large number of famous people, including cardinal Manning, sent Buchanan messages of approval.

The reaction of the critical journals was distinctly unfavorable to Buchanan, partly on account of the manner in which the original article had been published. In reviewing The Fleshly School of Poetry, and Other Phenomena of the Day, The Athenaeum 101 carefully recalls all the circumstances connected with the Contemporary Review attack. Buchanan’s mistakes, misinterpretations of literature, and injudicious confessions are ably ridiculed. He is depicted as an ingenuous Scotchman coming fresh from a tour in the Hebrides to search out symptoms of “the Leg-disease.” Even The Saturday Review 102 condemns the book for its flippancy, arrogance, and distemper. Something may be said for the unwholesomeness of Swinburne’s and Rossetti’s work, but the quotations from their writings are more objectionable when torn from their context. Buchanan has gathered from other poets a collection of salacious passages, of which he shows remarkable knowledge, in order to increase the interest in his pamphlet. The Saturday Review finds an inconsistency between his enjoying such writers as Whitman and Paul de Kock and being outraged by Rossetti or by confectionery. Sensualism may be spreading, but Buchanan’s Fleshly School of Poetry will minister to, rather than discourage, it.

Under the Microscope was an answer to The Fleshly School of Poetry, as well as to other detraction. Swinburne liked to maintain, however, that his book was a judicial discussion of such important questions as “the relative excellencies and shortcomings of Lord Byron and Mr. Tennyson as poets, and the respective merits and demerits of the first 176 poet of American democracy.” 103 To emphasize the impersonal nature of his treatise, Swinburne promises to devote a spare hour to the science of comparative entomology: a critic being what Blake once painted, the ghost of a flea. That specimen of the critical tribe known as the “anonym” merits attention first. One “anonym” meet for ridicule is the author of an article contrasting Tennyson’s morality unfavorably with Byron’s. 104 If Swinburne is correct, the same anonymous writer is responsible for a recent hostile review of some younger poets. 105 Having disposed of the “anonym,” Swinburne turns to the “coprophagi”—insects deriving their sustenance from uncleanness; the names of these he scorns to immortalize by mentioning. 108 As a specimen of those critics who incline to disparage their contemporaries, he names Alfred Austin, who had also contrasted Tennyson and Byron to the former’s disadvantage. 107 After showing the weakness of Austin’s method of comparison and defending the Laureate’s best work, he censures the latter’s treatment of the Arthurian legend. 108 Swinburne’s discussion of Walt Whitman was doubtless prompted by Austin’s disparagement, and Buchanan’s praise, of the American poet.

Though he makes allusions to still other critiques, 109 Swinburne’s heavy artillery is reserved for Buchanan. The latter is almost entirely ignored until near the end of Under the Microscope, reduced to the proportions of an insect, he is nevertheless the target for a broadside. Some of Buchanan’s injudicious comments about himself are cleverly introduced:

A living critic of no less note in the world of letters than himself has drawn public attention to the deep and delicate beauties of his work. . . . 110

After spurning the notion of a league among his friends to decry all reputation but their own and after emphasizing 177 Buchanan’s use of a pseudonym, Swinburne concludes with an excoriation of his most detested foe.

Though it hardly rises to the level of Notes on Poems and Reviews and is at times marred by a somewhat labored extravagance of denunciation, Under the Microscope does contain passages in which the irony is admirable. In comparison, Buchanan’s retort, in The Monkey and the Microscope, 111 is mere vituperation:

A clever Monkey—he can squeak,

Scream, bite, munch, mumble, all but speak;

Studies not merely monkey-sport,

But vices of a human sort;

Is petulant to most, but sweet

To those who pat him, give him meat . . .

Is amorous, and takes no pain

To hide his aphrodital vein;

And altogether, trimly drest

In human breeches, coat, and vest,

Looks human, and upon the whole

Lacks nothing, save perchance a Soul.

Although the critics did not, as I have pointed out, approve of Buchanan’s attack, their views on the relation of art and morality had not changed, 112 and they still found Swinburne’s poetry objectionable. 113 Under the Microscope was generally ignored, 114 though The Examiner published a deprecating notice. 115 Swinburne’s digression on Tennyson, moreover, brought a reproof from Richard Holt Hutton. 116

Before Swinburne’s controversy with Buchanan culminated in the famous trial of 1876, the poet hurled other verbal thunderbolts. Early in 1874, Ralph Waldo Emerson was reported as vigorously denouncing Swinburne. The nature of the denunciatory interview, of which Gosse 117 makes only vague and inaccurate mention, has hitherto remained a mystery, with the result that Swinburne has been 178 judged too harshly. After a long and almost hopeless search, I have at last succeeded in tracing the interview. It appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 118 for January 3, 1874. The passage relating to Swinburne follows:

He [Emerson] condemned Swinburne severely as a perfect leper and a mere sodomite, which criticism recalls Carlyle’s scathing description of that poet—as a man standing up to his neck in a cesspool, and adding to its contents. Morris, the author of “The Earthly Paradise,” is just the opposite of Swinburne, and will help to neutralize his bad influence on the public.

When Swinburne gave Emerson an opportunity to explain that he had been misquoted, no explanation was offered. Determined not to let such an affront go unpunished, Swinburne then sent Emerson a letter of astonishing violence. Unfortunately a copy of it was sent also to George Powell, 119 the poet’s friend, who unwisely had it turned over to the New York Daily Tribune 120 for publication. One sentence of the letter will indicate its tone:

A foul mouth is so ill matched with a white beard that I would gladly believe the newspaper scribes alone responsible for the bestial utterances which they declare to have dropped from a teacher whom such disciples as these exhibit, to our disgust and compassion, as performing on their obscene platform the last tricks of tongue now possible to a gap-toothed and hoary-headed ape, carried first into notice on the shoulder of Carlyle, and who now, in his dotage, spits and chatters from a dirtier perch of his own finding and fouling.

Such revolting language is, of course, inexcusable and sounds doubly so when applied to the mild-mannered philosopher of Concord. Nevertheless Swinburne was not the aggressor. When a man strikes a skilled pugilist and does not explain the blow as an accident, may he expect pleasant consequences? Such was Swinburne’s prowess in the use of 179 invective that he naturally routed his critics in the same way as he put his cabmen to flight. 121

Among those who read Swinburne’s letter in the Tribune was Paul Hamilton Hayne, the Southern poet. Hayne thus expresses his indignation to Whittier: 122

Please tell Mr. Emerson that but one feeling of intense disgust has greeted the appearance of that infamous letter, South, no less than North. Was ever such mean arrogance, such maudlin impudence, such colossal conceit obtruded before, upon the public view? The miserable scamp! Why his name ought to be spelt Swine-burn!

By 1875, however, Hayne was corresponding with Swinburne on most amicable terms 123 and later published some verses in his honor. 124

In May, 1875, there arose one of those squabbles over literary morality which seem destined to agitate the world through all eternity. Thomas Purnell called attention, in the columns of The Athenaeum, 125 to the fact that C. H. Collette, representing the Society for the Suppression of Vice, had secured the withdrawal of a translation of Rabelais, possibly “thinking it a squib by Mr. Swinburne.” In his reply 126 Collette defended himself “for suppressing the book entitled ‘Rabelais’” Colette’s phraseology supplied an irresistible temptation for Swinburne to enter the fray in support of Purnell, a friend who had earned his gratitude by being present at his first meeting with Mazzini, and Rabelais, a writer whom he adored. Collette’s blunder became a kind of chorus to which he returned with transparent delight:

The book entitled Milton is not so immaculate as the virtuous who have never read it may be fain to believe. Of the book entitled Dryden, the book entitled Pope, and the book entitled Swift, I need scarcely speak, and should indeed . . . prefer to pass them by with a shudder and a blush. 127 180

Collette’s response was that “Mr. Swinburne may, therefore, remain assured that neither the authors he names nor even his own works will be interfered with by the Society.” 128

Swinburne’s next indulgence of his penchant for irony proved more costly. In 1875 an anonymous poem entitled Jonas Fisher appeared—a dull, rambling work, full of windy discussions of theology and of such current topics as the legalizing of marriage with one’s deceased wife’s sister. Here is a sample of the author’s “humor”:

“What would you think, my friend, if made

To dig your garden with a spoon,

And eat your pudding with a spade?”

Jonas Fisher contrasts contemporary poetry with hat of the past. At Byron one need not shudder much,

“But what my very soul abhors,

What almost turns my blood to bile,

Is, when some prurient paganist

Stands up, and warbles with a smile

“A sick, putrescent, dulcet lay,—

Like sugared sauce with meat too high,—

To hymn, or hint, the sensuous charms

Of morbid immortality.” 129

Swinburne assumed that Buchanan had written Jonas Fisher, and accordingly he published in The Examiner for November 20, 1875, his Epitaph on a Slanderer. 130 In reviewing the book a week later, The Examiner took note of the rumor that it had been written either by Robert Buchanan or the Devil. Swinburne then composed his letter The Devil’s Due, the title of which is explained by this passage: “But it is certainly inconceivable that the authorship of any work whatever should be assignable with equal plausibility to the polypseudonymous lyrist and libeller in question and to the Satan of Milton, the Lucifer of Byron, or the Mephistopheles of 181 Goethe.” To his letter the poet signed “Thomas Maitland,” adding a postscript to the effect that the writer was on a cruise among the Philippine Islands. Buchanan brought suit against The Examiner and secured damages for one hundred fifty pounds. 131 In summing up the case the presiding judge is reported to have spoken as follows concerning the work of “the fleshly school”:

He was sure the jury would agree with him that much [of it] had better never have been written, and if all of it were consigned to the flames tomorrow, the world would be much the better.

This statement was made while Erechtheus was being hailed as a masterpiece. 132

Notes:

(pp. 302-305)

86. The Edinburgh Review, CXXXIV (July, 1871), 71-99. I have already referred to the denunciation of Songs before Sunrise in this article.

87. H. Buxton Forman, Our Living Poets. Forman declares Swinburne’s work offensive to morals and religion. Atalanta full of beauty and blatant antitheism, Mary Queen of Scots a strumpet, and Chastelard a glorified libertine. Anactoria and The Leper are (once more) horrible. The sonnets on Napoleon III are “poisonously inhuman.”

88. The Contemporary Review, XVIII (October, 1871), 334-50.

89. Walter Pater seems to have imagined a kind of Gampish Mrs. Harris—Aunt Fancy, “who fainted when the word ‘leg’ was mentioned.” Cf. Edmund Gosse, Critical Kit-Kats, p. 268.

90. Buchanan points to Swinburne’s and Morris’s praise of Rossetti. As a matter of fact, Rossetti did arrange to have his poems reviewed by friends. Cf. Oswald Doughty (editor), The Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti to His Publisher, F. S. Ellis, p.27.

91. The most satisfactory discussion of Baudelaire’s influence is Harold Nicolson’s “Swinburne and Baudelaire,” in Essays by Divers hands being the Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom, New Series, VI (London, 1926), 117-37, ed. G. K. Chesterton, I am sure Baudelaire had nothing to do with Swinburne’s fondness Sappho, for cats, or for a woman of the Mary Stuart type.

“I never had really much in common with Baudelaire, though I retain all my early admiration for his genius at his best,” writes Swinburne to William Sharp in 1901 (Letters, II, 259). This statement has been interpreted as a repudiation of Baudelaire. Cf. Nicolson, Swinburne, pp. 192-93. It seems to me a mere statement of fact. Such criticism as Buchanan’s may, however, help to account for Swinburne’s change of attitude, if there was a change.

92. Quoted in Wise, Bibliography, I, 230.

93. Cf. above, p. 293.

94. Quoted from Harriett Jay’s Robert Buchanan, p. 166.

95. See above, p. 62.

96. Cf. Some Reminiscences of William Michael Rossetti, pp. 521 ff.; William Michael Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family Letters, I, 294-301. In Hall Caine’s Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti Buchanan admitted that he had misjudged Rossetti, to whom he dedicated God and the Man. Buchanan’s A Look Round Literature contains A Note on Dante Rossetti and also friendly mention of Swinburne. See pp. 51, 373, 385. Neither Swinburne nor Watts-Dunton, whose sonnet The Octopus of the Golden Isles (see James Douglas’s Theodore Watts-Dunton, pp. 148-49) was inspired by Buchanan’s attack, ceased to cherish resentment towards the Scotchman. Cf. below, p. 322. For remarks about Buchanan see Hake and Compton-Rickett, Letters, pp. 87-88, 140, and The Ashley Library, VI 123.

97. By November 11, 1871, Swinburne had heard of Buchanan’s authorship through Frederick Locker. Cf. Letters to Frederick Locker, p. 8.

98. The Athenaeum, December 9, 1871, p. 755.

99. In The Pall Mall Gazette, December 23, 1871, p. 3. The statement of responsibility is not so clear as Buchanan implies.

100. Harriett Jay, op. cit., p. 163. The justice of her claim that Tennyson and Browning were tacitly in sympathy with Buchanan is more doubtful.

101. The Athenaeum, May 25, 1872, pp. 650-51.

102. The Saturday Review, XXXIII (June 1, 1872), 700-01, “Mr. Buchanan and the Fleshly Poets.” But an article called “Coterie Glory,” The Saturday Review, XXXIII (February 24, 1872), 239-40, had shown more sympathy with Buchanan.

The Examiner for May 18, 1872, p. 508, treats Buchanan’s pamphlet with severity.

103. See Letters to the Press, pp. 15-17.

104. Since there is no annotated edition of Under the Microscope, I shall indicate the various passages to which Swinburne alludes. The article referred to above is “Byron and Tennyson,” The Quarterly Review, CXXXI (October, 1871), 354-92, apparently by Abraham Hayward. Of The Princess Hayward writes (pp. 381-82): “We remember the time when it was considered the depth of ill-breeding and bad taste to allude to Odalisques or Anonymas in good society, it being assumed that matrons and damsels of high degree were not aware of the existence of such a class. It is rather strange, therefore, that the Princess should be so familiar with male objects of desire.” Cf. Under the Microscope, pp. 8, 9. Hayward also takes exception to The Sisters (p. 379); cf. Under the Microscope, p. 9.

105. Cf. above, p. 156, for my description of this article in The Quarterly Review, CXXXII (January, 1872), 59-84. The article speaks of “the revolting picturesqueness” of the sexual relation as portrayed in Rossetti’s sonnets, of the worship of priapus, of “emasculate obscenity” and profanity (p. 71); cf. Under the Microscope, p. 11. Of Swinburne the Quarterly Review writer observes: “We are in doubt whether to blame him most for his want of decency or want of sense” (p. 66)’ cf. Under the Microscope, p. 12. In connection with Swinburne’s pantheistic poems the reviewer asks (p. 65), “What, then, is the meaning of all this vapouring against a Being who is believed to be a nonentity?” Cf. Under the Microscope, p. 12.

106. It is likely that Swinburne had in mind, among other scurrilous reflections on his character, Mortimer Collins’s Two Plunges for a Pearl. See above, pp. 126 f. The poet alludes (p. 15) to “caricature,” which might well apply to Collins’s book. When this supposition first occurred to me, I had not yet read Mr. Wise’s privately printed pamphlet Letters from Dante Gabriel Rossetti to Algernon Charles Swinburne Regarding the Attacks Made upon the Latter by Mortimer Collins and upon Both by Robert Buchanan (London, 1921), a copy of which is in the British Museum. In a letter written November 11, 1871, Rossetti advises Swinburne that “complete contempt is the only possible answer to it [Two Plunges for a Pearl]. I do not mean to say that a lifelong training in the use of the fists or the horsewhip might not inevitably lead to another course of action, but in reality it is well that you should not give the cur even this kind of immortality” (the italics are mine; cf. the words italicized with Swinburne’s phraseology in Under the Microscope). On November 15, 1871, Rossetti writes, “I should like much to see what you wrote on the other unsavoury creature [Collins], but fancy in so foul a case as that it might perhaps be better to be silent.” Evidently what Swinburne wrote was not published.

Buchanan and Collins were friends.

107. See above, p. 139.

108. Swinburne’s remarks in this connection are unjustifiably severe. One of the leaves of his pamphlet, containing the most offensive passage, was canceled. On a canceled page Swinburne speaks of “that cycle of strumpets and scoundrels, broken by, here and there, an imbecile, which Mr. Tennyson has set revolving round the figure of his central wittol.” A misunderstanding in regard to this passage occasioned the misstatement, which I have encountered in print, that Swinburne called Tennyson a strumpet!

109. For the allusion (p.29) to a writer who had likened Swinburne to a boy rolling in a puddle, see above, p. 154. There are also derogatory remarks about Lowell (pp. 55 ff. and 87); cf. above, p. 23. A reference to a critic in The Contemporary Review I have already explained (above, p. 138).

110. Swinburne proceeds to quote from Buchanan’s David Gray and Other Essays.

111. The Saint Pauls Magazine, August, 1872, p. 240.

112. Two articles entitled Art and Morality are worth noting: the first of these, by G. A. Simcox, in Macmillan’s Magazine, XXVI (October, 1872), 487-92, condemns The Leper and Laus Veneris, as well as Tennyson’s Aylmer’s Field. An article in The Cornhill Magazine, XXXII (July, 1875), 91-101, without mentioning Swinburne’s name, implies condemnation: “Cynicism and prurience, and a voluptuous delight in cruelty and simply abominable, whoever possesses them, and however great his powers.”

113. I shall here take a brief inventory of some lesser detractors, nearly all hostile for moral reasons: “Novelties in Poetry and Criticism,” in Fraser’s Magazine, V, n. s. (May, 1872), 588-96, is directed chiefly against the aesthetic theories of the new school of poets. Joseph Devey’s A Comparative Estimate of Modern English Poets contains a chapter entitled “Androtheist School. Swinbourne [sic],” which follows Buchanan in comparing the English poet with French writers, Devey complains most about Swinburne’s attitude towards Christianity and his treatment of women, in contrast to Tennyson’s. “The State of English Poetry” in The Quarterly Review for July, 1873 (CXXXV, 39) refers to “the splendid but meaningless music of Mr. Swinburne, with his Herthas, his Hymns, his Litanies, and his Lamentations.” “Scepticism and Modern Poetry,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, CXV (February, 1874), 226, mentions Swinburne’s “audacious profanity.” “The Morality of ‘Don Juan’” in The Dublin University Magazine, LXXXV (May, 1875), 630-37, condemns “the prurient rhapsodists” of “the fleshly school,” pictured as the upholders of vice and opponents of virtue and religion. The writer quotes a famous line from Dolores. Thomas Bayne’s “Algernon Charles Swinburne,” St. James Magazine and United Empire Review, XXXI (1877), 436-47, finds Songs before Sunrise lacking in “statesmanship,” and discovers “sensuousness” even in Bothwell. Ethics and Aesthetics of Modern Poetry, by “J. B. Selkirk,” a pseudonym for James brown, includes some denunciation of Swinburne’s “blasphemy.” Cf. the article with the same title in The Cornhill Magazine, XXXVII (May, 1878), 569-83, and the earlier article on “Scepticism and Modern Poetry.” Frederic Harrison in “On the Choice of Books,” The Fortnightly Review, XXXI (April 1, 1879), 501, laments the fact that the young men at the universities seem to prefer Swinburne and other writers to Scott. Cf. The Choice of Books and Other Literary Pieces, p. 71. These notes make it clear that Buchanan’s Fleshly School of Poetry had some influence, but that the main trend of criticism continues in the same direction as when Poems and Ballads and Songs before Sunrise were first published.

114. Swinburne speaks of its “marked and utter neglect” (Letters, I. 94).

115. “Mr. Swinburne among the Fleas,” The Examiner, July 6, 1872, pp. 673-74.

116. See Hutton’s “Tennyson,” Macmillan’s Magazine, XXVII (December, 1872), 143-67, especially pp. 156, 159. In A Swinburne Library, p. 66, a letter is quoted in which the poet takes note of Hutton’s essay.

117. Life, p.211.

118. “Emerson: A Literary Interview,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 3, 1874, p.275.

119. Bonchurch Edition, XX, 451.

120. See the New York Daily Tribune for February 25, 1874, p. 4.

121. In A Study of Shakespeare (p. 159) Swinburne alludes to “an impudent and foul-mouthed Yankee philophaster” who had accused Landor of pestering him with Southey and had been rebuked by the old lion. In a letter to Paul Hamilton Hayne, published in the Boston Evening Transcript for October 16, 1918, Swinburne says that Emerson has exposed himself as “a foul-minded and foul-mouthed old driveller,” yet acknowledges that one or two of Emerson’s poems have exceptional beauty.

122. Whittier Correspondence, ed. John Albree, pp. 188-89; see also p. 179, where Hayne indicates his abhorrence of Swinburne’s philosophy.

123. Cf. Letters, I, 207-08.

124. Two sonnets “To Algernon Charles Swinburne,” Poems of Paul Hamilton Hayne (Boston, 1882), p. 269. The Southern poet, Sidney Lanier, contemporary with Hayne, never speaks of Swinburne except disparagingly. See Letters of Sidney Lanier (New York, 1899), pp. 25, 144, 205, 208. Cf. Edwin Mims, Sidney Lanier (Boston and New York, 1905), pp. 359, 366. “It is always the Fourth of July with Mr. Swinburne,” is Lanier’s most picturesque remark.

125. The Athenaeum, May 8, 1875, p. 622.~

126. Ibid., May 15, 1875, p. 655. Purnell responds in ibid., for May 22, 1875, p. 687.

127. Reprinted from The Athenaeum for May 29, 1875, p. 720, in Letters to the Press.

128. The Athenaeum, June 5, 1875, p. 750. See Letters, II, 34-35, for an interesting reference to Collette.

129. Jonas Fisher, p. 140.

130. Since no names are given, this bit of verse had nothing to do with the libel suit. It is reprinted in Nicoll and Wise, Literary Anecdotes of the Nineteenth Century, II, 354. A more amusing squib on Buchanan is that printed in The Ashley Library, VI, 112.

131. The London Times for June 30, July 1, and July 3, 1876, gives a report of the trial. Lord Southesk testified that he was the author of Jonas Fisher. Buchanan’s praise of Whitman was insisted upon by the defendant’s attorney as invalidating his right to attack English poets. His Session of the Poets, The Fleshly School of Poetry, as well as a poem of passion, The White Rose and Red, were discussed.

The proprietors of The Examiner had acknowledged that the second libel, The Devil’s Due, was the work of Swinburne, who had assumed responsibility for it. But Buchanan’s attorneys advised him to bring suit against The Examiner rather than against the poet. See the report of MacClymont, a counsel for the plaintiff, to John Nichol, printed in the Bonchurch Edition, XX, 136-39. In The Ashley Library, VI, 113, is a letter written by Swinburne in which he agrees to give The Examiner a poem, adding that the previous editor of that paper owed him forty-two pounds; this and other considerations kept him from feeling obligated because of his share in bringing about the trial.

132. Miss Jay cites a passage from The Christian World rejoicing over Buchanan’s vindication at the trial. See Robert Buchanan, pp. 164-66. H. D. Traill reports the “Jonas Fisher” episode amusingly in “A Literary ‘Cause Célèbre,’” included in Recaptured Rhymes (Edinburgh and London, 1882).

___

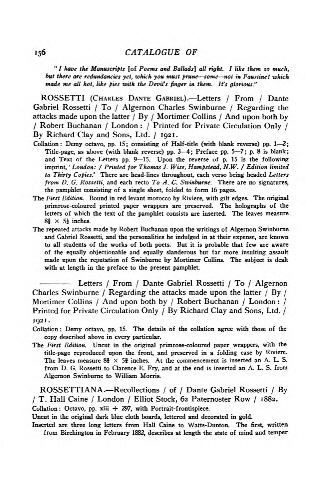

A couple of notes on Note 106 above. I have not come across any evidence of Buchanan being a friend of Mortimer Collins, author of the anti-Swinburne novel Two Plunges for a Pearl, but William Gaunt also mentions it in The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy (London: Jonathan Cape, 1942) - again with no supporting facts. Also, Hyder’s book was originally published in 1933. The following year Thomas Wise’s reputation was severely damaged and he was revealed as a forger. So the material mentioned in the Notes relating to Thomas Wise and the Ashley Library is a bit dodgy. Here’s the page referred to in Note 106:

|