ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HARRIETT JAY BOOK REVIEWS

3. My Connaught Cousins (1883) to The Strange Adventures Of Miss Brown (1897)

The Academy (23 December, 1882) My Connaught Cousins. In 3 vols. By Harriett Jay. (White.) There was no necessity for a prefatory note by Mr. Robert Buchanan to My Connaught Cousins; the book is quite pleasant and quite intelligible enough to stand on its own merits. It is written with a lively and intelligent sympathy with the Irish people by one who evidently enters into the tragic elements of the Irish character arising from the impulsive warmth of feeling and incompleteness of development, which must leave its destiny a question not to be solved in any time near our own, but still to call out the disinterested efforts and fruitful sympathy of leaders of the future. Jack Stedman, the hero, is invited to a typical Irish home, full of that joyous hospitality, that courteous kindliness and perfect freedom, which make up the associations which most people have with Irish visits. Six delightful cousins vie in their efforts to spoil him; and, of course, Oona, the most beautiful, is the heroine. The prospects of the book looked doubtful when Jack set himself to read Oona’s MS.; but her story is better than anything Jack writes of his own; in fact, it becomes plain that his visit is chiefly a framework to introduce these somewhat wild, but interesting, Irish stories. Oona’s tale of the two brothers; Nora’s, of “The Maid of Cruna Island;” and, best of all, Kathleen’s, of “Rose Merton,” are well worth reading—the last too sadly worth remembering in the light of recent Irish affairs. In addition to the stories with which he is regaled, Jack Stedman becomes interested in the characters around him, and has some admirable opportunities of studying the landlord question (which he leaves with most disheartening results, we must confess) and the customs and claims so dear to the hearts of a people who can never be rightly judged until they are seen and known in their own homes. There is little artistic effort, but there is genuine pathos and the sympathetic feeling which goes far to solving vexed questions, in My Connaught Cousins. ___

The Daily News (29 December, 1882) RECENT NOVELS. We should have thought that the original power and intrinsic worth of Miss Harriett Jay’s Irish romances would have made their way with the public without the aid, if aid it be, of expostulation or exhortation from her friends. Her brother- in-law, Mr. Robert Buchanan, has, however, deemed it desirable to prefix a prefatory note to her last novel, “My Connaught Cousins” (3 vols., F. V. White and Co.), in which he disclaims, on the author’s account, any hostile feeling to Irish nationality, and utters a protest against what he calls the neglect with which some, at any rate, of her books have been received. This seems to us surprising, for, while Miss Jay’s stories have received an amount of opposition which is inevitable to works dealing with disturbed political questions, neglect is the last condition we should have believed them abandoned to. We have been under the impression that they were widely read and exceedingly well-known. No one could write a novel about Ireland and he Irish of the present day which would be worth reading if it did not contain views which would be contradicted by one side or the other. Miss Jay’s novel “The Priest’s Blessing” presented a view of the relations of the peasantry to their priesthood and the nature of the influence of the priest which must inevitably have aroused opposition only bitterer for the evident sincerity of the author’s conviction. It was as Mr. Buchanan says, a “powerful social study,” and, though some readers thought it mistaken or one-sided, most people thought it worth reading. Perhaps there is no country which presents at the moment so many and so widely-differing social aspects as Ireland, and about which so many positively true and absolutely different notions can be expressed. It all depends on the point of view. In “My Connaught Cousins,” as in previous works, Miss Jay exhibits a generous and warm sympathy with the suffering people and a keen observation of the temperament, at any rate, of the class her story lies amongst. To say that the peasants of her Connaught country are in many ways very unlike the peasants of Ulster is only to re-state the truism that Ireland is a country of self-contradictions. In the main the qualities of the Celtic temperament are everywhere alike. But, to take only a small social question as a test of accuracy, we should like to know what the priests and doctors of Ireland generally would say to Miss Jay’s fourth chapter, in which Father John and Doctor Maguire are described as “martyred men, lugubrious, monosyllabic” because they were temporarily divorced from the whiskey bottle, only recovering their jocund spirits on breaking self-imposed pledges and swallowing quantities of raw spirits. “My Connaught Cousins” is not so much an ordinary novel as a series of local sketches, sometimes, as in that we have just alluded to, a little over-coloured, and occasionally showing traces of hasty arrangement. It fully displays, however, the author’s fresh and lively descriptive power and vivid style. ___

The Graphic (6 January, 1883) Miss Harriett Jay, in “My Connaught Cousins” (3 vols.: F. V. White and Co.), has most effectively given some of the results of her intimacy with the people and the traditions of Western Ireland. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s preface is not needed to vouch for the sincerity and the power of the pen that wrote the “Queen of Connaught” and “The Priest’s Blessing,” or for the breadth of Miss Jay’s social and political sympathies. The present work is a collection of sketches and tales—how far the latter are collected, original, or adapted, Miss Jay best knows—illustrating life and character in the remotest West, arranged and connected by a pleasant holiday setting in the form of a prosperous love story. All this is managed with such skill and such variety of charm that few will be tempted to charge the general effect with being a little one-sided. The “stupid and cowardly Saxon” is, in truth, only too swift and too eager to sympathise with the characteristics of that island which is so resolutely determined to consider itself miscomprehended. Miss Jay has brought out all the good that thousands besides herself have found in the quick and warmhearted West, and those who know her scenery the best will thank her the most for confirming their own experiences in so adequate and so delightful a way. ___

The Morning Post (8 January, 1883 - p.3) MY CONNAUGHT COUSINS.* Miss Jay occupies a prominent place among writers of fiction as a delineator of Irish life and character. She has none of the bright drollery and humour of Lever, nor do her sketches show the careful finish of those by Carleton, but the outlines of her pictures are clear and vivid, and she is a deeply-convinced exposer of Irish grievances. Her latest work, “My Connaught Cousins,” is as fresh and original as its predecessors. It has, however, less merit as a novel then, for instance, her “Queen of Connaught,” as it has really no plot. The arrival of a young London barrister on a visit to his cousins in wild Connemara, one of whom he learns to love and at last marries, does not deserve the name. The author’s present work consists of a series of varied pictures of landlord and peasant life in Connemara. These pictures are presented to the reader either as incidents occurring to the family of Mr. Kenmare or in tales told by his young daughter to their London cousin. Among the finest of these is the legend of “Kildare Castle.” The tragedy enacted between the unfortunate Antony and his handsome brother Conn is forcibly told, and the contrast between Alma Clifford’s somewhat weak character and her stern surroundings very striking. Miss Jay’s descriptions of the rude, savage coast of Connemara are excellent. Whether when the storm wind lashes the waves of the great Atlantic into fury, or when the trembling rays of the rising sun glitter on its surface calm as a mountain lake and tinged with the ever-varying hues of the opal, the author’s facility for brilliant word painting is never better shown than in depicting the natural features of this little known but picturesque region. Miss Jay’s account of some customs of Irish life, although bearing the stamp of truth, will doubtless surprise the general reader. Few know that a Connemara peasant match is an affair of barter between the parents of the parties concerned, and is concluded with an utter disregard for the mutual feelings of the young people, as was the case of old, when the contracting parties belonged to families of the old French noblesse. Pretty Norah MacDermott, in accordance with established usage, is offered for “five cows, two fat pigs, a strong donkey for drawing turf, and three pounds in gold, to a man of forty, hideous in face, deformed—an evident bully and tyrant.” Norah’s way of getting out of this cruel predicament is ingenious. Pretending to submit to paternal will she seeks her favoured lover, and proposes to him to make a forcible entry into her chamber by the window, and so carry her off, “But only a hundred yards or so from the house, Owen dear, then ye know ye are safe to keep me, because neither Corney Beg nor any dacent boy would take me after that, even if I had double the fortune.” And Norah’s device being carried out from point to point, she is duly married to the man of her heart. In the character of James Merton the author has drawn the type of the Irish peasant, driven by cruel wrong-doing to crime, which to his heated imagination has become a sacred duty. The picture of his miserable hut, unroofed by his master’s orders, while his unhappy wife is in her death agony, is dark and sombre as the subject which inspires it. After such scenes of horror it is difficult to condemn with sufficient severity murders like that of young Gregory’s. It is only too true that such things have been; and that from a variety of causes, many of them inherent to the soil, the lives of the Irish peasantry in many counties have fallen in very hard places. But the fault of romance writers when treating burning social and political questions is that, like Mrs. Beecher Stowe in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” they make out the exception to be the rule, and give an entirely one-sided view of the situation. That Miss Jay has not avoided this error will be patent to the dispassionate reader. That works like hers at the present moment can but add fuel to a flame already too widely spread will also strike impartial minds. Apart from this, Miss Jay has in her present novel given another proof of dramatic skill united to a style at once varied and graphic. *My Connaught Cousins. By Harriett Jay. London: F. V. White and Co. ___

John Bull (13 January, 1883 - p.12) The Connaught Cousins* who give a title to Miss Jay’s new novel merely occupy the place of a rather slender thread on which certain thrilling episodes of Irish life are suspended by the author. The opening chapter tells how a hard-worked London barrister gets an invitation to Connaught from an uncle, whom he only knows as the father of six female cousins, the whole family being yet unseen by him. Miss Jay has by this time established her reputation as one of the most earnest and successful contemporary writers of Irish fiction; while, in her case, enthusiasm for the people is so largely tempered with clear-sightedness and common sense, that she would probably not be admitted as a true patriot by those whose cause she endeavours to advance. In The Priest’s Blessing, one of her latest stories, she gives a most vivid, and, we believe, truthful picture of some of the less recognised among the evil influences which surround the unhappy and impressionable Irishman. There was an intensity about the whole tale which made it almost oppressive to read, and which is entirely absent from My Connaught Cousins. The effect which in the one case was heightened almost to luridness by concentration, is in the other so interrupted, diffused, and broken up that it is almost lost. The little sketches of Irish life, which one of the young ladies relates to her cousin are many of them extremely interesting and well told, but they are too fragmentary to retain much hold on the reader’s imagination; while the thread which unites them will either bore him as superfluous altogether, or appear to him so much the more interesting part of the book that he will resent the length and frequency of the stories which break it. Mr. Robert Buchanan introduces the work with a brief preface, which does not serve much purpose beyond coupling a well-known name with Miss Jay’s latest effort for the cause which she has at heart. *My Connaught Cousins. By Harriett Jay. In Three Vols.—London: F. V. White and Co., 1883. ___

The Standard (18 January, 1883 - p.2) “My Connaught Cousins.” By Harriet Jay, Author of “The Queen of Connaught, “ Two Men and a Maid,” &c. Three Vols. London: F. V. White and Co.—In a rather flatulent preface Mr. Robert Buchanan orders us to recognise Miss Jay’s novels as works of genius, and assures us that Mr. Charles Reade and himself greatly admire them. A young English barrister pays a visit to his Irish uncle, Mr. Kenmare, of Ballyshanrany. Mr. Kenmare has half a dozen charming daughters. With one of them, the beautiful Oona, her cousin, Jack Stedman, falls in love. The six sisters tell him a great many Irish legends—An agent is killed, and a landlord shot at. Mr. Kenmare, who is held up to us as the soul of honour, could have convicted the would-be assassin, but under the reign of terror prevailing in Ireland he knew the consequences of giving truthful evidence, and he could not brave them. “I remembered my girls,” he said. “I pictured to myself what they would feel sitting together round the dead body of their old father, and for the life of me I could not speak.” “My Connaught Cousins” is like a good many other books about Ireland. There is nothing in it at all striking or original, or deserving of Mr. Buchanan’s pompous eulogy. A novelist should not give to fictitious noblemen the titles of existing Peers. Does Miss Jay know that there is a real Lord Antrim? ___

The Spectator (14 July, 1883 - p.22) My Connaught Cousins, by Harriett Jay (White), is not an improvement upon “The Queen of Connaught,” or even “The Priest’s Blessing.” Miss Jay seems to have made a mistake in writing not a single story, but a collection of tales connected by a very slender thread of narrative. Of these, the story of Rose Merton is the most powerful, and the most decidedly Irish. The character, however, of the offending landlord, who, of course, comes to a violent end, seems to us to be unnecessarily repulsive. Rose Merton herself is well drawn, and the “Connaught cousins” are such pleasant girls, and their father is such a good Irish type, that one wishes Miss Jay had paid more attention to them, and less to Irish miseries and grievances. Stedman, who visits them, and into whose arms Oona, the dreamer and story-teller of the number, falls rather too readily at the end of the third volume, is a very conventional London barrister; and Miss Jay’s humour is rather farcical, and too redolent of whisky even for Ireland. The Connaught Cousins would have been all the better without a heavy-shotted “Prefatory Note,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan, which savours too much of the art of the puffiste littéraire. ___

Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser (Dublin) (30 November, 1883) The Messrs. F. V. White and Company, London, have issued three popular novels in a 2s. edition. “My Connaught Cousins,” by Harriet Jay, is already well known to us on account, mainly, of its strange mixture of ignorance and knowledge concerning the Irish character. The prefatory note, from the pen of Robert Buchanan, in which that gallant tries to explain away the seeming hostility displayed by the authoress towards our nationality, is quite a feature in the volume.—“My Sister the Actress,” by Florence Marryat, who ought, from experience, to know better than to use the present tense right through a long story, has been found, no doubt, to possess a fascinating influence over some minds.— “The Dean’s Wife,” by Mrs. Eiloart, can boast of a great many points in its favour. For all which reasons these books are welcome in the cheap form. _____

|

|

|

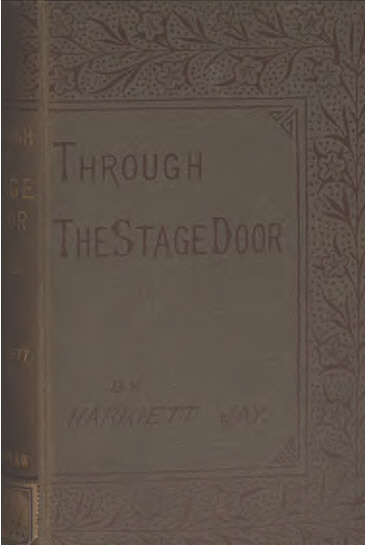

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (17 November, 1883 - p.7) No less than four of the novels of the season introduce their readers to the world behind the stage—to the world, either as it is, or as it seems to be to the imagination of the romance-writer. It is, of course, under the former category that Miss Florence Marryat’s stories naturally come since this authoress has been—perhaps, indeed, she still is—on the stage herself. She has already written, “My Sister the Actress,” the second edition of her new tale, “Peeress and Player,” is just out, and now she promises “Facing the Footlights” immediately. Then we also have Miss Edith Stewart Drury’s “Only an Actress,” and Miss Harriett Jay contributes what are, we presume, autobiographical sketches in her “Through the Stage Door.” Altogether it is clear that the subject is receiving its full due of attention at the circulating libraries. ___

The Spectator (15 December, 1883) Through the Stage Door: a Novel. By Harriett Jay. (F. V. White.)—This is a regrettable book. The coarse vices of bad men are not material whereof women should weave their fictions. If they know anything about the matter by experience in their own families, they ought to conceal that sad knowledge; if they have to draw on their imagination for the facts, they render themselves unpleasantly ridiculous. The “Mr. George” of Miss Jay’s novel, who is a married Duke, and the relation to him of two of the female actors in the story, are exceedingly repulsive features of a novel which has no attractive ones. The writer does her work so carelessly that she makes Mr. Fane, the father of her heroine, when he wants to escape the sounds of household contention, “stuff his fingers into his ears, and continue his writing;” describes a room as “luxuriantly furnished,” and a young lady as being “fully as elated as if she had known, &c.,” writes of “invitations pouring in fast and furious” on a fashionable young man, who is blest with “an overflowing card-basket,” and of young ladies’ “drinking down” champagne. The very vulgar company of this novel is, however, preferable to its fine company; a lady who intercepts letters, and bribes her nephew to ruin the reputation of her brother’s betrothed wife; and another lady who tells her husband that she is sure their expected guest “will come to their house in the finery of a street- walker,” are much more offensive persons than the Fane family. The latter are not at all original; we have met them in many trashy novels, in which grave and gallant English gentlemen—mostly military—select their wives from “the juvenile lead;” although it must be admitted there is something remarkable about Miss Lottie. It is not every young lady who figures in tights of whom it can be said, “The necessary stage training had added to her manner a naïveté which she might not otherwise have possessed.” We have hitherto regarded stage training as a potent corrector of naïveté. ___

The Academy (15 December, 1883) NEW NOVELS. A Christmas Rose. By Mrs. Randolph. In 3 vols. (Hurst & Blackett.) ... Miss Jay has taught her readers to look for vigorous work at her hands, so that her very merit is to blame if this latest book of hers causes some disappointment to her readers. It is far from dull, is even bright and easy, but it lacks the strength and freshness we naturally expect from her; nor is it written from the inside. The story is slight, being that a wealthy and middle-aged officer falls in love at the theatre with a good and pretty actress of burlesque, Lottie Fane, and desires to make her his wife; but, after he has won her conditional assent, mischief is made, with the object of parting them, by his sister and a half-adopted ward of his, whose interest it is that he should not marry. The usual intercepting of letters is the main agency employed, and all the latter part of the tale is occupied with the trouble which comes in consequence, and the means taken for setting it right. The theatrical portions, though cleverly sketched, do not seem derived from first-hand knowledge; and the self-contained little heroine and her kindly, but boisterous, sister are the only characters which are not mere lay figures. And the Camden Town household, with a meek, industrious, kindly little father, much put upon by his gloomily majestic wife, whose tragic utterances are constantly snubbed by her younger daughter, while the elder consoles their father, is almost a transcript from the Wilfer family in Our Mutual Friend. Miss Jay has originality enough not to need the help of plagiarism, and no one would take such well-known goods wittingly; but the resemblance is so close that unconscious memory must have been at work when she was writing that episode of her story. ___

The Illustrated London News (15 December, 1883 - p.19) Of writing theatrical novels lately there has been no end; indeed, every lady novelist who has sat in the stalls of a theatre seems to have felt it her duty to give an account of the life which is enacted behind the scenes, of which in reality she knows nothing. The result has been a series of theatrical fictions giving pictures of a kind of stage life which existed nowhere except in the author’s brains. We are the more pleased, therefore, to welcome a story from the pen of a lady who has not only taken a good position among living novelists, but whose experiences as an actress entitle her to give us a picture of life behind the scenes as it really is. Through the Stage Door, by Miss Harriet Jay (White and Co.), is a novel which bears upon every page the imprint of truth. The story is simple enough: it is merely the record of the life of an actress, a good hard-working girl, who loves her profession and her home, who is unfortunate in her love, and who leaves and finally returns to the stage. Out of these everyday materials the experienced hand of the authoress has woven a most charming and interesting tale; and, while telling it, Miss Jay has chosen to branch off occasionally and give us glimpses of the other and darker side of theatrical life—to present to us, indeed, scenes which are morbidly unwholesome, and which here and there overstep the bounds of decency. True, some of them—notably the evening at the Belladonna Club and the dinner between two ladies of rather doubtful reputation—are drawn with a vividness which attests their truthfulness; but we think the book would have been better, certainly it would have been purer and more wholesome, if such scenes had been altogether omitted. Still there is much in it that is good and pure; the characters are well and distinctly drawn, the authoress’s power of word painting is so vivid, and the story is told with so much dramatic force as to make it worthy to rank with the admirable stories by which Miss Jay had previously become known. ___

The Graphic (19 January, 1884) At a time when everything relating to the stage is of such supreme interest as it is, Miss Harriett Jay’s “Through the Stage Door” (3 vols. : F. V. White and Co.) must be considered eminently well-timed. The inner life of the stage, painted by a successful actress, claims a popular value of its own, independently of the literary merits safe to be found in any work by the authoress of “The Queen of Connaught” and “The Dark Colleen.” Considered merely as a novel, we do not think that “Through the Stage Door” is nearly equal in merit to Miss Jay’s studies of modern Irish life and character. It is in the serious portraiture of strong passions among appropriate surroundings that she most excels, and something of the unreality of the stage attaches to the persons and situations of her new theatrical novel. Possibly, however, this was to some extent indispensable, especially as she has preferred to deal with her subject lightly.She has certainly not fallen into the grotesque and common error of idealising the still little known world that lies behind the scenes, nor is her picture likely to attract young ladies and gentlemen who are smitten with the taste of the hour. Her heroine, Lottie Fane, and Lottie’s lively sister, Carrie, illustrate possibilities of combining innocence and good sense under the most adverse circumstances; but then these adverse circumstances are dwelt upon no less strongly. Of course the heroine’s charm is brought out all the more effectively by force of contrast not only with the difficulties of her domestic and public life, but with the household of the man whom she is so fortunate to obtain for her lover, and finally for her husband. Miss Jay holds the balance evenly throughout, between whatever reasons have in any period injured the stage in social estimation and those dull and stupid prejudices which go far to keep the stage from vindicating itself, and gaining the full recognition bestowed upon other arts so freely. In short, the novel admits the due amount of right and wrong on both sides of the question, and amply shows how much more human interest attaches to the life of the stage as it really is than to those monstrous illusions hitherto given to the world as theatrical novels. That actors and actresses are just men and women is a piece of knowledge which is still uncommon; and Miss Jay’s interesting and able story will help to promulgate this truth. ___

The Spectator (2 February, 1884 - p.23) Through the Stage Door. By Harriett Jay. 3 vols. (F. V. White and Co.)—We are inclined to think that this is the best, as it is certainly the pleasantest, story that Miss Jay has yet given to the world. It is true that there are some very disreputable people that figure in it, and places described, “the Belladonna Club,” for instance, which young women, not to say young men, had best know nothing about; but the effect of the book generally is good, and its tone sound and wholesome. Carlotta and Caroline Fane, daughters of a family which has been for generations connected with the drama, are two actresses in burlesque. Carlotta is the heroine of the story, and Caroline plays the second part. The love-affairs of the latter move smoothly enough. She is engaged to a comic singer at music-halls, a very worthy young fellow, we are glad to hear, and marries him. She is a very intelligent and determined young person, with a temper of her own, as all good women, it is said, have. Carlotta’s fortunes are much more complex. A certain Colonel Sedgemore, a man of good family and fortune, falls in love with her. His family naturally object. How they scheme against her, and how the scheming ends, is told here in a very lively story, which we have read with much pleasure, and can recommend anyhow to older readers. The two sisters are a pair of as good, honest girls as ever were described in a novel, and are amusing withal. Amusing also in another way is the tragédienne, their mother, a humble follower of Mrs. Siddons; and Mr. Fane, also a professional man, bnt who has not risen beyond the height of prompter, till, indeed, the growing fame of his daughters, who rise from burlesque to Shakespeare, brings him elevation. Mr. Fane astonishes us on p. 16, when he, “stuffs his fingers into his ears and continues his writing;” but he turns out to be nothing more than the ordinary “heavy father,” only excellently well described. Through the Stage Door may seem frivolous beside grave works of fiction that deal with Irish difficulties, but it is a great deal more readable. ___

The Standard (4 February, 1884 - p.3) WAITING FOR THE VERDICT. TO THE EDITOR OF THE STANDARD. SIR,—In the Spectator of December 15 appeared a review of a novel from my pen entitled “Through the Stage Door,” containing the following severe strictures:—“This is a regrettable book. The coarse vices of bad men are not material whereof women should weave their fictions. If they know anything about the matter by experience in their own families they ought to conceal the sad knowledge; if they have to draw on their imagination for the facts they render themselves unpleasantly ridiculous. . . . Exceedingly repulsive features of a novel which has no attractive ones. . . . The very vulgar company of this novel is, however, preferable to its fine company. . . . The Fane family are not at all original, we have met them in many trashy novels, although it must be admitted there is something remarkable about Miss Lottie. It is not every young lady who figures in tights of whom it can be said, ‘the necessary stage training had added to her manner a naïveté which she might not otherwise have possessed.” ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (4 February, 1884) The old literary maxim that no one can ever be written out of a reputation save by himself is undoubtedly sound, and as a general rule nothing can be less wise than for a writer to criticise his critics. But there are exceptions to the rule. Mr. Whistler’s famous critical catalogue, for instance, raised a well-deserved laugh by no means against himself; and there is a letter in the Standard this morning which furnishes another case in point. It will surely go hard with the authoress of “Through the Stage Door” if the public does not feel a good deal of curiosity about a novel which one and the same journal describes as “exceedingly repulsive” and eminently “readable” and “pleasant.” The highest function of criticism, as every one knows, is to find out the best that can be known; but there is an even larger impartiality in saying at the same time the best and the worst that can be said. ___

The Academy (9 February, 1884) A NEW DEPARTURE IN CRITICISM. Your contemporary the Spectator is a journal which I have always looked upon with the greatest respect. Its high moral fervour is well known, as well as its freedom from religious bias; but I think the world knows little of its wonderful catholicity in matters of literary criticism, of which I have just furnished the Standard with a remarkable illustration. HARRIETT JAY. ___

The Standard (18 February, 1884 - p.2) “Through the Stage Door.” By Harriet Jay, Author of “The Queen of Connaught.” Three Vols. F. V. White and Co. —The Colonel is a curious character. He can find no woman worthy of his hand in his own rank of life; but he tumbles headlong into love with a little burlesque dancer, and is ready to take to his arms the whole of her very vulgar family. But he gives her up very easily, and leads a fast life without being himself fast, and forms a platonic friendship for a notoriously bad woman, who finally proves herself a good angel to him and his little dancer. No one but a fool or a bigot would question the purity and honesty of many ballet girls; but there are others from whose life it can serve no purpose to draw the veil. The atmosphere of a green-room is believed by outsiders to have some subtle and mysterious charms of its own. Here it is represented as licentious and vulgar, but certainly not alluring. Of many absurd incidents in this novel perhaps the most silly is that in which Colonel Sedgemore is represented as throwing flowers from the stage box to the actress whom he had deserted for her infidelity. Could any man have had such a fiend of a sister as Mrs. Crowe for forty years without finding it out? ___

The Daily News (1 March, 1884) It seems singular that the natural talent of Miss Harriett Jay, her literary associations and her experience of the theatre, should not enable her to produce anything better in the way of a theatrical novel than “Through the Stage Door” (3 vols., F. V. White and Co.). The tone is pitched throughout on a level with the attainments of the burlesque actresses whose story it professes to tell, for, though Miss Lottie Fane takes to Shakespeare after her love disappointments and performs Rosalind to her pert sister’s Celia, the reader is not enabled to realise any idea of her performance of the part or in any sense to “see her in it.” It is difficult to believe that the same hand wrote this poor novel as that which wrote the “Queen of Connaught,” and other stories of power and meaning. ___

The Derby Mercury (9 July, 1884 - p.6) [A comparison of Florence Marryat’s My Sister the Actress and Harriett Jay’s Through the Stage Door, including lengthy extracts from both, can be accessed by clicking the image below.] |

|

|

A Marriage of Convenience (1885)

The Derby Mercury (2 July, 1884) A new serial story by Miss Harriet Jay, authoress of “The Queen of Connaught,” “Through the Stage Door,” &c., will be commenced in the Lady’s Pictorial early this month. A series of papers, by Miss Emily Faithfull, on “Life among the Mormons,” will also shortly appear in the same paper. ___

The Morning Post (9 July, 1885 - p.2) A MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE.* Besides her many other gifts as a novelist Miss Jay possesses that of great versatility. There is a gulf between the scenes and incidents of her well-known work, “The Queen of Connaught,” and her latest production. It would have been disappointing had so clever an author written a mere “Society novel,” whatever its merit. “A Marriage of Convenience,” although belonging to the above category, is yet something more than others of its class. Highly dramatic as is the plot, it owes much of its thrilling interest and originality to the sort of medieval element brought into it by the nationality of one of its chief characters, the Duke d’Azzeglio. From the moment at which the Spanish grandee appears upon the scene the commonplace vanishes. It is instantly felt that the story will be pervaded by an unusually dramatic colouring, that the Duke’s wrongs, if any are done him, will be avenged by means savouring of a feudal age, and that he will hate and love with the intense passion of his race and clime. Unfortunately no noble or generous feeling redeems the misdeeds of a man great only from the circumstances of birth. From first to last powerfully written, it may be safely predicted that this work will be one of the most successful novels of the season. * A Marriage of Convenience. By Harriett Jay. London: F. V. White and Co. ___

The Graphic (22 August, 1885) Miss Harriet Jay’s “A Marriage of Convenience” (3 vols.: F. V. White and Co.), is not by any means up to the level to which the authoress of “Queen of Connaught” has accustomed her readers. We fear it must be classed with the results of the art of book-making—it certainly bears all the signs of fatal hurry. It contains powerful passages here and there, but they seem always to have dropped into the work by accident, as the result of some chance inspiration, and not as that of any clear and harmonious design. The characters are stagey to extravagance—the melodramatic Spanish Duke, the man who has vowed life-long vengeance against him and follows him like a sleuth-hound, the stern old lady who also lives for an incomprehensible or rather lunatic revenge, the persecuted heroine, and all the rest of them. The footlights never cease to glare between the reader and the stage: and the situations correspond to the characters—or rather, while the latter are merely conventionally extravagant, the former are impossible. We have had so constantly to speak with unqualified admiration of Miss Jay’s work that we are the more bound to note the first symptom of indifference to what is due from an artist to her art. Nobody can be always at his or her best: but novels like “A Marriage of Convenience” are best left in the limbo of the magazines—in one of which, to judge from the periodical recurrence of a fainting fit or some other temporary climax, the story probably first appeared. _____

The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown (1897)

The Referee (7 February, 1897 - p.3) The play by Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Charles Marlowe called “The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown” has been published by Mr. Buchanan in the form of a novel, of which the authorship is attributed solely to Charles Marlowe, who now stands confessed as Harriett Jay. A reproduction of a photograph of Miss Jay—dressed in the fashion of a bygone day—is given, with the signature of “Charles Marlowe” beneath it. The story certainly recalls the touch of Charles Marlowe rather than the style of the more gifted novelist who made a hit years ago with the story of “The Queen of Connaught,” in the days of once upon a time when there lived a distinguished poet of the name of Robert Buchanan. ___

The Scotsman (8 February, 1897 - p.2) The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown. By Charles Marlowe (Harriet Jay.) London: Robert Buchanan. A three-act comedy has already been founded on The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown, and perusal of the tale might even suggest that it was originally written for stage presentation. The characters are the beings of modern comedy; the main incidents demand of the reader a certain blindness to probability commonly required in drama. The story is that of the marriage of a ward in Chancery to a young military captain. The marriage ceremony is scarcely performed when Angela is recaptured by her guardian, and conveyed back to the boarding-school from which she has fled. Thither her husband follows her, dressed in female attire; and the doings of the harmless Don Juan, who goes by the name of Miss Brown, are amusing enough. In the end, when everything has reached a crisis, it is announced that the captain has succeeded to a peerage. The objections to the marriage are thus removed, and the course of true love is smoothed. The tale is entertainingly written. ___

The Globe (22 February, 1897 - p.6) It would appear that the farcical comedy by Mr. Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” called “The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown,” and performed successfully both at the Vaudeville and at Terry’s, was founded upon a humorous story by the latter writer, now openly revealed to us as Miss Harriett Jay. Mr. Buchanan himself publishes the story (at Gerrard-street, Shaftesbury-avenue), and a portrait of Miss Jay forms the pictorial frontispiece. Those who saw the comedy represented will be curious to observe how the incidents and dialogue look in narrative form, and those who never witnessed the play will no doubt be attracted to “The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown” in its character of a novel merely. The whole thing is extravagant of course; but it is bright and lively, and calculated to make a long railway journey seem short. It has not much literary merit, but it diverts. ___

Glasgow Herald (25 February, 1897) The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown. By Charles Marlowe (Harriet Jay). (London: Robert Buchanan.)—One hardly needs to be reminded that this story is of close kin to “the popular three-act comedy produced in 1895 at the Vaudeville Theatre, London, and still running in England and America.” There is all the delightfully conventional improbability of stageland in the runaway marriage of the gallant young officer and the Chancery ward, and especially in the stratagem whereby Captain Courtenay, until matters are smoothed by his succession to a peerage, introduces himself as a parlour boarder into the ladies’ seminary to which his bride has been brought back by her legal guardians. Quite stagely orthodox, too, are the characters—the impassive captain himself and his romantic inamorata, the friendly Irish major who swears “by the saints” and possesses a warm-hearted Irish wife full of infinite resources for the aid of distressed lovers, the sentimental confidante, the prim schoolmistress, the philandering music-master, and all the other personages necessary for the conduct of an innocent little intrigue. The structure of the story, in fact, is rather that of the play than of the novel, and the various chapters are really dramatic scenes turned into narrative. None the less the book is a thoroughly brisk and amusing one, well fitted for the employment of a vacant hour. ___

The Stage (25 March, 1897 - p.13) Robert Buchanan, publisher amongst his other vocations, has issued in one-volume novel form, “The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown.” This is the story from which the play of that name was dramatised. “Charles Marlowe,” otherwise clever Miss Harriett Jay, is the author. The book is much upon the same plan as the extravagant piece, and will, no doubt, like the latter, find very many to enjoy it. ___

The Era (10 April, 1897) “THE STRANGE ADVENTURES OF MISS BROWN.” By CHARLES MARLOWE (HARRIETT JAY). London: Robert Buchanan, Gerrard-street, W.—Few farces are amusing reading, and one is therefore agreeably surprised to find that The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown stands so well the ordeal of cold print. But then we have a right to expect excellent work from so experienced an authoress as Miss Harriett Jay. The story told in the book runs exactly on the same lines as that acted at the theatre, except that it was thought prudent to transfer to a drawing-room the scene between Angela Brightwell, Miss Schultz, and “Miss Brown” that in the novel is located in a bedroom. Those who have seen the play will be able to revive memories of pleasant evenings at the theatre, and those whose knowledge of “Miss Brown” will be derived from the book will find “her” worth knowing. ___

The Morning Post (17 April, 1897 - p.2) THE STRANGE ADVENTURES OF MISS BROWN.* Some may incline to think that there is more of farce than of comedy in this most amusing book, but to this opinion objections may reasonably be made. Although the personages not seldom find themselves in ludicrous situations, they are well defined, and have in themselves nothing of the exaggeration which is one of the necessary elements of farce. Take, for instance, Miss Brown, otherwise Captain Courtenay, whose adventures are told in a manner that might have imparted a sense of humour to Diogenes. He is as “brave a soldier as ever wore uniform,” clever, but with a demeanour remarkable for its stolidity. The circumstances in which the author ingeniously places him are absurd, but in spite of all he never degenerates into a clown, and manages all through to retain a considerable amount of dignity. Of course, probability is set aside when the cheery O’Gallaghers are made to appear ignorant of the gravity of the consequences that may result from the step to which they urge the lovers. But why be hypocritical when almost every page is brimful of fun. The Major, to do him justice, does entertain apprehensions, and represents to his wife that the proposed bride is “only eighteen, and a ward in Chancery.” But his irrepressible wife, instead of feeling impressed, insults the majesty of the law by exclaiming, “Yes, the poor darling. Without father or mother to look after her, and only a deputy Providence in the shape of an old gentleman with a wig.” Once the marriage over, and the bride back again in Miss Romney’s select academy, while the bridegroom, hiding from justice, weaves plots to effect her deliverance, the mirth becomes fast and furious. From first to last Courtenay is too good for the empty-headed, silly school-girl his imagination has transformed into a goddess. He is such a thoroughly excellent fellow that one leaves him with regret, and also the warm-hearted O’Gallaghers. Angela perhaps learns to live up to the good fortune that befalls her. At any rate, gratitude is owing to them all for the amusement they have been made to afford not only in this novel but in the play in which they had already appeared. *The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown. By Charles Marlowe (Harriett Jay). 1 vol. London: Robert Buchanan. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (28 April, 1897 - p.7) “The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown.” By Charles Marlowe (Harriett Jay). (London: Robert Buchanan.) Any one desiring a couple of hours’ light reading is recommended to purchase this production of “Charles Marlowe’s” facile and skilful pen. It is not now occupied with sketching the Irish scenes and people with which it is so familiar, but in describing the adventures of an English officer, who essays to marry a ward in Chancery without the consent of the Lord Chancellor. When it is said that the exigencies of the case drive Captain Courtenay to the desperate expedient of figuring in a highly respectable school for young ladies as “Miss Brown,” it will be seen that there is room for an abundant display of humour. It may be said that the literary merits of the story are far above the material here indicated, being very cleverly written. We observe that the volume is published by Mr. Robert Buchanan, the well-known novelist and poet. _____

Harriett Jay Book Reviews continued Robert Buchanan: Some Account of His Life, or back to Harriett Jay Bibliography

|

|

|

|

|

|

|