ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

UNDER THE MICROSCOPE

__________

450 copies of this book have

__________

UNDER THE BY ALGERNON CHARLES

PORTLAND MAINE

__________

PREFACE

__________ vii PREFACE WHEN the history of the calamities and quarrels of modern authors comes to be written out in detail it is very certain that the period in English letters between 1860-1875 will demand and receive respectful attention. Foremost among the documents humains, which the bitter animosities aroused by Robert Buchanan’s blatant and brutal attack1 upon Rossetti, Swinburne and Morris, brought to the surface, must ever remain, “through glad and sorry years,” the rare pamphlet we now reprint.2 _____ 1 The Fleshly School of Poetry and Other Phenomena of the Day. By Robert Buchanan. Strahan & Co., 56, Ludgate Hill, London, 1872. Octavo, pink wrapper, pp. x: 97. 2 Under | the Microscope. | By | Algernon Charles Swinburne. | London: | D. White, 22, Coventry Street, W, | 1872. Collation:—Crown octavo, pp. iv. +88; consisting of Half-title (with blank reverse), pp. i.-ii.; Title-page, as above (with imprint: “London: | Savill, Edwards and Co., Printers, Chandos Street, | Covent Garden,” upon the centre of the reverse), pp. iii.-iv., and Text pp. 1-88. Page 32, last line but one—for monsieurs, read messieurs. |

|

“ 72, line 18—for Hugos, read Hugo’s. Upon examining any copy of Under the Microscope it will be observed that Sig. D 5 (pp. 41-42) is a cancel-leaf. The original leaf was widely suppressed, as certain of the expressions used in relation to the characters of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King were unduly harsh. The following passage, describing “the courteous and loyal Gawain of the old romancers” as “the very vilest figure in all that cycle of strumpets and scoundrels, broken by, here and there, an imbecile, which Mr. Tennyson has set revolving round the figure of his central wittol,” is unjust as well as severe. It is believed that only two copies of this cancelled leaf were preserved. _____ viii exhaustless vocabulary of vituperation. Compared with this terrific invective, the earlier printed protest of Rossetti is almost in the nature of a compliment!3 _____ 3 The Stealthy School of Criticism in the Athenæum for December 16, 1871. Reprinted in Rossetti’s Collected Works, 2 vols., 8vo. (London, 1886.) _____ ix whose slight claims as poet were set forth and disallowed by Mr. Swinburne in 1867.4 Either this or an unwise desire to pose as literary censor, mixed with and marred by immedicable envy of the men he singled out for reprobation, seems to us the secret source of irritation lying back of the entire controversy.5 _____ 4 See Matthew Arnold’s New Poems by A. C. Swinburne in the Fortnightly Review for October, 1867, since re-issued in his Essays and Studies (1875). 5 The animus against his brother, according to Mr. W. M. Rossetti, “should be regarded as a vicarious expression of resentment” at the following remark which opened his review entitled Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads, a Criticism (1866): “The advent of a new great poet is sure to cause a commotion of one kind or another; and it would be hard were this otherwise in times like ours, when the advent of even so poor and pretentious a poetaster as a Robert Buchanan stirs storms in teapots.” (Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family Letters with a Memoir by W. M. Rossetti. London, 1895. Vol. I, p. 294.) _____ x artistic mistake was ever made than that of deferring to this preposterous criticism, as it is conceded that the original text of the Poems (1870) was of unblemished beauty. _____ 6 See Appendix III. 7 On the contrary he printed a rather neat rejoinder in one of the defunct periodicals of that day. See Appendix II.

__________

UNDER THE MICROSCOPE

__________ 1 WE live in an age when not to be scientific is to be nothing; the man untrained in science, though he should speak with the tongues of men and of angels, though he should know all that man may know of the history of men and their works in time past, though he should have nourished on the study of their noblest examples in art and literature whatever he may have of natural intelligence, is but a pitiable and worthless pretender in the sight of professors to whom natural science is not a mean but an end; not an instrument of priceless worth for the mental workman, but a result in itself satisfying and final, a substitute in place of an auxiliary, a sovereign in lieu of an ally, a goal instead of a chariot.It is not enough in their eyes to admit that all study of details is precious or necessary to help us to a larger and surer knowledge of the whole; that without the invaluable support and illumination of practical research and physical science, the human intellect must still as of old go limping and blinking on its way nowhither, lame of one foot at best and blind of one eye; the knowledge of bones and stones is good not merely as a part of that general knowledge of 2 nature inward as well as outward, human as well as other, towards which the mind would fain make its way yet a little and again a little further through all obstruction of error and suffusion of mystery; it is in the bones and stones themselves, not in man at all or the works of man, that we are to find the ultimate satisfaction and the crowning interest of our studies. Not because the study of such things will rid us of traditional obstacles that lay in the way of free and fruitful thought, will clear the air of mythologic malaria, will purge the spiritual city from religious pestilence; not because each one new certitude attained must involve the overthrow of more illusions than one, and every fact we can gather brings us by so much nearer to the truth we seek, serves as it were for a single brick or beam in the great house of knowledge that all students and thinkers who have served the world or are to serve it have borne or will bear their part in helping to construct. The facts are not of value simply because they serve the truth; nor are there so many mansions as once we may have thought in this house of truth, nor so many ministers in its service. It is vain to reply, while admitting that truth cannot be reached by men who take no due account of facts, that each fact is not all the truth, each limb is not all the body, each thought is not all the mind; and that even men (if such there be) ignorant of everything but what other men have written may 3 possibly not be ignorant of everything worth knowledge, destitute of every capacity worth exercise. One study alone, and one form of study, is worthy the time and the respect of men who would escape the contempt of their kind. Impressed by this consideration— impelled by late regret and tardy ambition to atone if possible for lost time and thought misspent—I have determined to devote at least a spare hour to the science of comparative entomology; and propose here to set down in a few loose notes the modest outcome of my morning’s researches. “How sweet is chastity in hoary hairs! Or perchance there may rise to our own lips the equally impressive tribute of a French writer at the same venerable shrine. “Vieillard, ton âme austère est une âme d’élite: I know not whether the rebuke of venerable virtue had power to affect the callous conscience of the '”hoarse-voiced satyr” thus convicted of “the depth of ill-breeding and bad taste;” but I cannot doubt that when in January a like parable was taken up in the same quarter against certain younger offenders, the thought that the same voice with the same weight of judgment in its tones was raised to denounce them must have struck cold to their hearts while it brought the blood to their cheeks. The likeness in turn of phrase and inflexion of voice was perfect; the air of age and authority, if indeed it was but assumed, was assumed with faultless and exquisite fidelity; the choice of points for attack and words to attack with was as nearly as might be identical. “No terms of condemnation could be too strong,” so rang that “terrible voice of most just judgment,” “for the revolting picturesqueness of A’s description of the sexual relation;” it was illustrated by sacramental symbols 11 of “gross profanity;” it gave evidence of “emasculate obscenity,”* and a deliberate addiction to “the worship of Priapus.” The virtuous journalist, I have observed, is remarkably fond of Priapus; his frequent and forcible allusions to “the honest garden-god” recur with a devout iteration to be found in no other worshipper; for one such reference in graver or lighter verse you may find a score in prose of the moral and critical sort. Long since, in that incomparable satiric essay which won for its young author the deathless applause of Balzac—“magnifique préface d’un livre magnifique”—Théophile Gautier had occasion to remark on the intimate familiarity of the virtuous journalist with all the occult obscenities of literature, the depth and width of range which his studies in that line would seem to have taken, if we might judge by his numerous and ready citations of the titles of indecent books with which he would associate the title of the book reviewed. This problematic intimacy the French poet finds no plausible way to explain; and with it we must leave the other problem on which I have touched above, in the hope that some day a more advanced stage of scientific _____ * “Climène. Il a une obscénité qui n’est pas supportable. _____ 12 inquiry will produce men competent to resolve it. Meantime we may remark again the very twang of the former preacher in the voice which now denounces to our ridicule B’s “want of sense,” while it invokes our disgust as fire from heaven on his “want of decency,” in the use of a type borrowed from the Christian mythology and applied to actual doings and sufferings; and once more we surely seem to “know the sweet Roman hand” that sets down our errors in its register, when the critic remarks on the absurd inconsequence of a poet who addresses by name and denounces in person a god in whose personal existence he does not believe. In the name of all divine persons that ever did or did not exist, what on earth or in heaven would the critic in such a case expect? Is it from the believers in a particular god or gods that he would look for exposure and denunciation of their especial creed? Would it be natural and rational for a man to attack and denounce a name he believes in or a person he adores, unnatural and irrational to attack and denounce by name a godhead or a gospel he finds incredible and abominable to him? When a great poetess apostrophized the gods of Hellas as dead, was the form of apostrophe made inconsequent and absurd by the fact that she did not believe them to be alive? For a choicer specimen of preacher’s logic than this we might seek long without finding it. But we must not be led away into argument or answer 13 addressed to the subjects of our research, while as yet the work before us remains unaccomplished. The self-imposed task is simple and severe; we would merely submit to the analysis of scientific examination the examiners of other men; bring under our microscope, as it were, the telescopic apparatus which they on their side bring to investigate from below things otherwise invisible to them, as they would be imperceptible from above but for the microscopic lens which science enables us in turn to apply to themselves and their appliances. As to answer, if any workman who has done any work of his own should be asked why he does not come forward to take up any challenge flung down to him, or sweep out of his way any litter of lies and insults that may chance to encumber it for a moment, his reply for his fellows and himself to those who suggest that they should engage in such a warfare might perhaps run somewhat thus: Are we cranes or mice, that we should give battle to the frogs or the pigmies? Examine them we may at our leisure, in the pursuit of natural history, if our studies should chance to have taken that turn; but as we cannot, when they speak out of the darkness, tell frog from frog by his croak, or pigmy from pigmy by his features, and are thus liable at every moment to the most unscientific errors in definition, it seems best to seek no further for quaint or notable examples of a kind which we cannot profitably attempt 14 to classify. Not without regret, therefore, we resign to more adventurous explorers the whole range of the anonymous wilderness, and confine our own modest researches to the limits within which we may trust ourselves to make no grave mistakes of kind. But within these limits, too, there is a race which defies even scientific handling, and for a reason yet graver and more final. Among writers who publish and sign such things as they have to say about or against their contemporaries, there is still, as of old, a class which is protected against response or remark, as (to use an apt example of Macaulay’s) “the skunk is protected against the hunters. It is safe, because it is too filthy to handle, and too noisome even to approach.” To this class belong the creatures known to naturalists by the generic term of coprophagi; a generation which derives its sustenance from the unclean matter which produced it, and lives on the very stuff of which it was born: “They are no vipers, yet they feed and under this head we find ranked, for example, the workers and dealers in false and foul ware for minor magazines and newspapers, to whom now that they know their ears to be safe from the pillory and their shoulders from the scourge there is no restraint and no reply applicable but the restraint and the reply of the law which 15 imposes on their kind the brand of a shameful penalty; and it is not every day that an honest man will care to come forward and procure its infliction on some representative rascal of the tribe at the price of having to swear that the spittle aimed at his face came from the lips of a liar; that he has not lived on such terms of intimacy with the honest gentleman at the bar that the confidential and circumstantial report given of his life and opinions, habits and theories, person and conversation, is absolutely to be taken for gospel by the curious in such matters. The age of Pope is past, and we no longer expect a man of note to dive into the common sink of letters for the purpose of unearthing from its native place and nailing up by the throat in sight of day any chance vermin that may slink out in foul weather to assail him. The celebrity of Oldmixon and Curll is no longer attainable by dint of scurrilous persistency in provocation; in vain may the sons of the sewer look up with longing eyes after the hope of such peculiar immortality as that bestowed by Swift on the names of Whiston and Ditton: upon their upturned faces there will fall no drop or flake of such unfragrant fame. When some one told Dr. Johnson that a noted libeller had been publicly kicked in the streets of Dublin, his answer was to the effect that he was glad to hear of so clever a man rising so rapidly in the world; when he was in London, no one at whom his 16 personalities might be launched ever thought it worth whileto kick him. There are writers apparently consumed by a vain ambition to emulate the rise in life thus achieved by one of their precursors; and it takes them some time to discover, and despond as they admit, that such luck is not always to be looked for. Some, as in fond hope of such notice, assume the gay patrician in their style, while others in preference affect the honest plebeian; but in neither case do they succeed in attracting the touch which might confer celebrity; the very means they take to draw it down on themselves suffice to keep it off; at each fresh emanation or exhalation of their malodorous souls it becomes more clearly impossible for man to approach them even “with stopped nostril and glove-guarded hand.” When the dirtier lackeys of literature come forward in cast clothes to revile or to represent their betters, to caricature by personation or by defamation the masters of the house, men do not now look at them and pass by; they pass without looking, and have neither eye for the pretentions nor cudgel for the backs of the Marquis de Mascarille and the Vicomte de Jodelet. “Et, dans la goutte d’eau, les guerres du volvoce In all times there have been men in plenty convinced of the decadence of their own age; of which they have not usually been classed among the more distinguished children. We are happy in having among us a critic of some culture and of much noisy pertinacity who will serve well enough to represent the tribe. I distinguish his book on “The Poetry of the Period,” supplemented as I take it to be by further essays in criticism thrown out in the same line, not for any controversial purpose, 18 and assuredly with no view of attempting to answer or to confute the verdicts therein issued, to prove by force of reasoning or proclaim by force of rhetoric that the gulf between past and present is less deep and distinct than this author believes and alleges it to be; that the dead were not so far above the average type of men, that the living are not so far below it, as writers of this type have always been equally prone to maintain. I have little taste for such controversy and little belief in its value; but even if the diversion of arguing as to what sort of work should be done or is being done or has been were in my mind preferable to the business of doing as seems to me best whatever work my hand finds to do, I should not enter into a debate in which my own name was mixed up. Whether the men of this time be men of a great age or a small is not a matter to be decided by their own assertion or denial; but in any case a man of any generation can keep his hand and foot out of the perpetual wrangle and jangle of “the petty fools of rhyme who shriek and sweat in pigmy jars,” which recur in every age of literature with a pitiful repetition of the same cries and catchwords. I could never understand, and certainly I could never admire, the habit of mind or the form of energy which finds work and vent in demonstration or proclamation of the incompetence for all good of other men; but much less can I admire or understand the impulse which 19 would thrust a man forward to shriek out in reply some assertion of his own injured merit and the value of the work which he for instance has done for the world even in this much maligned generation. No man can prove or disprove his own worth except by his own work; and is it after all so grave a question to determine whether the merit of that be more or less? The world in its time will not want for great men, though he in his time be never so small; and if, small or great, he be a man of any courage or of any sense, he will find comfort and delight enough to last his time in the quite unmistakeably and indubitably great work of other men past or present, without any such irritable prurience of appetite for personal fame or hankering retrospection of regret for any foiled ambitions of his own. This temper of mind, which all men should be able to attain, must preserve him from the unprofitable and ignoble sufferings of fools and cowards; and self-contempt, the appointed scourge of all envious egotists, will have no sting for him. And once aware that his actual merit or demerit is no such mighty matter in the world’s eye, and the success or failure of his own life’s work in any line of thought or action is probably not of any incalculable importance to his own age or the next, the man who has learnt not to care overmuch about his real rank and relation to other workmen as greater or less than they, will hardly trouble himself overmuch 20 about the opinions held or expressed as to that rank and relation. What is said of him must be either true or false; if false, he would simply be a fool—if true, he would also be a coward—to wish it unsaid; for a lie in the end hurts none but the liar, and a truth is at all times profitable to all. In any case then it can do him no damage; for good work and worthy to last is indestructible; and to destroy with all due speed any destructible person or book not worthy to last is no injury to any one whatever, but the greatest service that can be done to the book and the writer themselves, not less—nay perhaps much more—than to the rest of the poor world which has no mind to be “pestered with such water-flies—diminutives of nature.” In a word, whatever is fit to live is safe to live, and whatever is not fit to live is sure to die, though all men should swear and struggle to the contrary; and it is hard to say which of these is the more consoling certainty. I shall not, therefore, select any book for refutation of its principle, but merely for examination of its argument; my only aim being to test by this simplest of means what may be its purport and its weight. I find for instance that Mr. Austin, satirist and critic by profession, writing with a plain emphatic energy and decision which make his essays on the poetry of the period easily and pleasantly readable by students of the minute, maintains throughout his book the opposition between two leading figures; the same figures since chosen 21 for the same purpose by the venerable monitor at whose feet we have already sat attentive and shrunk rebuked. In Byron the mighty past and in Tennyson the petty present is incarnate; other giants of less prominence are ranked behind the former, other pigmies of less proportion are gathered about the latter; but throughout it is assumed that no fairer example than either could be found of the best that his age had to show. We may admit for a moment the assumption that Byron was as indisputably at the head of his own generation, as indisputably its fittest and fullest representative, as we all allow Mr. Tennyson to be of his; and this assumption we may admit, because Mr. Austin is so good and complete a type of one class of the great critical kind, that by such a concession we may enable ourselves to get a clear view and a firm grasp of some definable principles of criticism; and thus to examine as we proposed the arguments on which these are based, and which we approach with no prepense design or premeditated aim to corroborate or to confute them, but simply to investigate. With a writer less clear and less forcible in purpose and in style we might not hope to get sight or hold of any principle at all; but this one, right or wrong and wise or unwise, at least does not babble to no purpose whatever like the “blind mouths” that prattle by mere chance of impulse or of habit. First then we observe that he offers us samples of either poet’s work with a great 22 show of fairness in the choice of representative passages; he bids us, like a new Hamlet rebuking the weakness and the shame of his mother-age, look here upon this picture and on this; and a counterfeit presentment it is indeed that he shows us. Taking an instance from his final essay, the summary and result of the book, we find a few lines from a slight poem of Mr. Tennyson’s extreme youth, and one which is by no means a fair exampleof even his earliest manner, set against the most famous and the finest passage but one in “Childe Harold”—the description of an Alpine thunder-storm.With equal justice and with equal profit we might pick out the worst refuse of dolorous doggrel from the rubbish-heaps of “Hours of Idleness” or “Hebrew Melodies”—say that version of the 137th Psalm so admirably parodied by Landor, of which the indignant shade of Hopkins might howl rejection, while the milder ghost of Brady would dissolve in air if accused of it—that or such another rag or shard of verse from the sweepings of Byron’s bad work—and set it against the majestic close of the “Lotus-eaters” or some passage of most finished exaltation from “In Memoriam.” But the critic has yet a better trick than this, ingenious and ingenuous as it is, to pervert the judgment of those who might chance to take his evidence on trust. He has copied accurately the short passage chosen to show the immature genius of Tennyson at its feeblest; but the longer passage chosen, 23 and very well chosen, to show the mature genius of Byron at its mightiest, he has been careful to alter and improve by the studious and judicious excision of two whole intervening stanzas; the second good in itself, but introduced by one stolen from Coleridge and deformed almost past recognition from a thing of supreme and perfect beauty into a formless and tuneless mass of clumsy verbosity and floundering incoherence. Even thus garbled and disembowelled, the passage, noble and delightful as in the main it is, stands yet defaced by two lines which no poet of the first order could have committed; two lines showing such hideous deficiency of instinct, such helpless want of the imaginative sense which in the highest poets is as strong and as sure to preserve from error as to impel towards perfection, that any man with an inner ear for that twin-born music of coequal thought and word without which there is no high poetry possible, must feel with all regret that here is not one of the poets who can be trusted by those who would enjoy them; but one who at the highest and smoothest of his full-winged flight is liable to some horrible collapse or flap of a dislocated pinion. The first offence is that monstrous simile—monstrous at once and mean—of “the light of a dark eye in woman,” which must surely have been stolen from Hayley; if even the author of the “Triumphs of Temper” can ever have thought a woman’s eye an apt and noble likeness for the whole heaven 24 of night in storm. This is the true sign of flawed or defective imagination; that a man should think, because the comparison of a woman’s eye to a stormy night may be striking and ennobling, therefore the inverted comparison of a stormy night to a woman’s eye must also be proper and impressive. The second offence is yet worse; it is that incomparable phrase of the mountains “rejoicing o’er a young earthquake’s birth,” which again I should conjecture to have been borrowed from Elkanah Settle; it is really much in the manner of some lines cited from that poet by Scott in his notes on Dryden. A young earthquake! why not a young toothache, a young spasm, or a young sneeze? We see the difference between sense and nonsense, pure imagination and mere turbid energy, when we turn to a phrase of Shelley’s on the same subject. “Is this the scene There is a symbol conceivable by the mind’s eye, noble and coherent. But to such critics as Mr. Austin it is all one; for them there are no such fine-drawn distinctions between words with a meaning and words without—with them, as with poor Elkanah, “if they rhyme and rattle, all is well.” This selection and collocation of fragmentary passages, it will be said, is not the best way to attain a fair and serious estimate of either poet’s worth or station; Byron may be or may 25 not be as much greater than Tennyson as the critic shall please, but this is not a sufficient process of proof. Nor assuredly do I think it is; but the method chosen is none of mine; it is the method chosen by the critic whom for the moment I follow to examine his system of criticism. His choice of an instance is designedly injurious to the poet whom it shows at his weakest; but it seems to me, however undesignedly, not much less injurious to the poet whom it shows at his strongest. Such is frequently the effect of such tactics, the net result and upshot of such an advocate’s good intentions. It will hardly be supposed that I have dwelt with any delight on the disparaging scrutiny of an otherwise admirable extract from a poet in whose praise I should have said enough elsewhere to stand clear of any possible charge of injustice or incompetence to enjoy his glorious and ardent genius; I have dwelt indeed with a genuine delight on a task far different from this—the task of praising with all my might, and if with superfluous yet certainly with sincere expression, his magnificent quality of communion with the great things of nature and translation of the joyous and terrible sense they give us of her living infinity, which has been given in like degree to no living poet but one greater far than Byron—the author of the Contemplations and the Légende des Siècles. This tribute, however inadequate and however unnecessary, was paid to the memory of Byron 26 before ever his latest English panegyrist laid lance in rest against all comers in defence of his fame; using meantime that fame as a stalking-horse behind which to shoot at the fame of others. And as to his assumed office of spokesman on behalf of Byron—a very noble office it would be if there were any need or place for it—we cannot but ask who gave him his credentials as advocate or apologist for a poet whose fame was to all seeming as secure as any man’s? Is the name of Byron fallen so low that such a style of advocacy and such a class of counsel must be sought out to revive its drooping credit and refresh its withered honours? Quis vituperavit? Has any one attacked his noble memory as a poet or a man, except here and there a journalist of the tribe of Levi or Tartuffe, or a blatant Bassarid of Boston, a rampant Mænad of Massachusetts? To wipe off the froth of falsehood from the foaming lips of inebriated virtue, when fresh from the sexless orgies of morality and reeling from the delirious riot of religion, may doubtless be a charitable office; but it is no proof of critical sense or judgment to set about the vindication of a great man as though his repute could by any chance be widely or durably affected by the confidences exchanged in the most secret place and hour of their sacred rites, far from the clamour of public halls and platforms made hoarse with holiness, Ubi sacra sancta acutis ululatibus agitant, 27 between two whispering priestesses of whatever god presides over the most vicious parts of virtue, the most shameless rites of modesty, the most rancorous forms of forgiveness—the very Floralia of evangelical faith and love. That two such spirits, naked and not ashamed, should so have met and mingled in the communion of calumny, have taken each with devout avidity her part in the obscene sacrament of hate, her share in the graceless eucharist of evil-speaking, is not more wonderful or more important than that the elder devotee should have duped the younger into a belief that she alone had been admitted to partake of a fouler feast than that eaten in mockery at a witch’s sabbath, a wafer more impure from a table more unspeakably polluted—the bread of slander from the altar of madness or malignity, the bitter poison of a shrine on which the cloven tongue of hell-fire might ever be expected to reappear with the return of some infernal Pentecost. All this is as natural and as insignificant as that the younger priestess on her part should since have trafficked in the unhallowed elements of their common and unclean mystery, have revealed for hire the unsacred secrets of no Eleusinian initiation. To whom can it matter that such a plume-plucked Celæno as this should come with all the filth and flutter of her kind to defile a grave which is safe and high enough above the abomination of her approach? Not, I should have thought, to those 28 who hold most in honour all that was worthiest of men’s honour in Byron. Surely he needs no defence against this posthumous conjugal effusion at second-hand of such a venomous and virulent charity as might shame the veriest Christian to have shown. And who else speaks evil of him but now and then some priest or pedagogue, frocked or unfrocked, in lecture or review? It should be remembered that a warfare carried into such quarters can bring honour or profit to no man. We are not accustomed to give back railing for railing that is flung at us from the pulpit or the street-corner. In the church as in the highway, the skirt significant of sex, be it surpliced or draggle- tailed, should suffice to protect the wearer from any reciprocity of vituperation. If it should ever be a clerical writer, whether of the regular or the secular order—an amateur who officiates by choice or by chance, or a registered official whose services are duly salaried—that may happen to review a book in which you may happen to have touched unawares on some naked nerve of his religious feeling or professional faith, you are not moved to any surprise or anger that he should liken you to a boy rolling in a puddle, or laugh at you in pity as he throws aside in disgust the proof of your fatuous ignorance; you know that this is the rhetoric or the reasoning of his kind, and that he means by it no more than a street-walker means by her curse as you pass by without 29 response to her addresses; you remember that both alike may claim the freedom of the trade, and would as soon turn back to notice the one salutation as the other. Priests and prostitutes are a privileged class. Half of that axiom was long since laid down by Shelley; and it is not from any such quarter that he probably would have thought the fame of his friend in any such danger as to require much demonstration of championship. The worst enemies of Byron, as of all his kind, are not to be sought among such as these. They are his enemies who extol him for gifts which he had not and work which he could not do; who by dint of praising him for such qualities as were wanting to his genius call the attention of all men to his want of them; who are not content to pay all homage to his unsurpassed energy, his fiery eloquence, his fitful but gigantic force of spirit, his troubled but triumphant strength of soul; to his passionate courage, his noble wrath and pity and scorn, his bright and burning wit, the invincible vitality and sleepless vigour of action and motion which informs and imbues for us all his better part of work as with a sense of living and personal power; who are dissatisfied for him with this his just and natural part of praise, and by way of doing him right must needs rise up to glorify him for imagination, of which he had little, and harmony, of which he had none. Even when supporting himself as in “Manfred” on the 30 wings of other poets, he cannot fly as straight or sing as true as they. It is not the mere fluid melody of dulcet and facile verse that is wanting to him; that he might want and be none the worse for want of it; it is the inner sense of harmony which cannot but speak in music, the innate and spiritual instinct of sweetness and fitness and exaltation which cannot but express itself in height and perfection of song. This divine concord is never infringed or violated in the stormiest symphonies of passion or imagination by any one of the supreme and sovereign poets: by Æschylus or Shakespeare, in the tempest and agony of Prometheus or of Lear, it is no less surely and naturally preserved than by Sophocles or by Milton in the serener departure of Œdipus or the more temperate lament of Samson. In a free country Mr. Austin or any other citizen may of course take leave to set Byron beside Shelley or above him, as Byron himself had leave to set Pope beside or above Shakespeare and Milton; there is no harm done in either case even to Pope or Byron, and assuredly there is no harm done to the greater poets. The one thing memorable in the matter is the confidence with which men who have absolutely no sense whatever of verbal music will pronounce judgment on the subtlest questions relating to that form of art.A man whose ear is conscious of no difference between Offenbach and Beethoven does not usually stand up as a judge of 31 instrumental music; but there is no ear so hirsute or so hard, so pointed or so long, that its wearer will not feel himself qualified to pass sentence on the musical rank of any poet’s verse, the relative range and value of his metrical power or skill. If one man says for instance that Shelley outsang all rivals while Byron could not properly sing at all, and another man in reply is good enough to inform him that what he meant to say and should have said was that Byron could not shriek in falsetto like Shelley and himself, the one betweenwhiles and the other at all times, what answer or appeal is possible? The decision must be left to each man’s own sense of hearing, or to his estimate of the respective worth of the two opinions given. I have always thought it somewhat hasty on the part of Sir Hugh Evans to condemn as “affectations” that phrase of Pistol’s—“He hears with ears;” to hear with ears is a gift by no means given to every man that wears them. Our own meanwhile are still plagued with the cackle of such judges on all points of art as those to whom Molière addressed himself in vain—“qui blâment et louent tout à contre-sens, prennent par où ils peuvent les termes de l’art qu’ils attrapent, et ne manquent jamais de les estropier et de les mettre hors de place. Hé! morbleu! messieurs, taisezvous. Quand Dieu ne vous a pas donné la connaissance d’une chose, n’apprétez point à rire à ceux qui vous entendent 32 parler; et songez qu’en ne disant mot on croira peut-être que vous êtes d’habiles gens.” Such another critic as Mr. Austin is Herr Elze, the German biographer, who has been sent among us after many days to inform our native ignorance that Byron was the greatest lyric poet of England. A few more such examples should have been vouchsafed us of “things not generally known;” such as these for instance: that our greatest dramatic poet was Dr. Johnson, our greatest comic poet was Sir Isaac Newton, our best amatory poet was Lord Bacon, our best religious poet was Lord Rochester, our best narrative poet was Joseph Addison, and our greatest epic poet was Tom Moore. Add to these the facts that Shakespeare’s fame rests on his invention of gunpowder, and Milton’s on his discovery of vaccination, and the student thus prepared and primed with useful knowledge will in time be qualified to match our instructor himself for accurate science of English literature, biographical or critical. It is a truth neither more nor less disputable than these that Byron was a great lyric poet; if the statements proposed above be true, then that also is true; if they be not, it also is not. He could no more have written a thoroughly good and perfect lyric, great or small, after the fashion of Hugo or after the fashion of Tennyson, than he could have written a page of Hamlet or of Paradise Lost. Even in the “Isles of Greece,” excellent 33 as the poem is throughout for eloquence and force, he stumbles into epigram or subsides into reflection with untimely lapse of rhetoric and unseemly change of note. The stanza on Miltiades is an almost vulgar instance of oratorical trick—“a very palpable hit” it might be on a platform, but it is a very palpable flaw in a lyric. Will it again be objected that such dissection as this of a poem is but a paltry and injurious form of criticism? Doubtless it is; but the test of true and great poetry is just this; that it will endure, if need be, such a process of analysis or anatomy; that thus tried as in the fire and decomposed as in a crucible it comes out after all renewed and re-attested in perfection of all its parts, in solid and flawless unity, whole and indissoluble. Scarcely one or two of all Byron’s poems will stand any such test for a moment: and his enemies, it must again be explained, are those eyeless and earless panegyrists who will not let us overlook this infirmity. It is to Byron and not to Tennyson that Mr. Austin has proved himself an enemy; the enemies of Tennyson are critics of another class: they are those of his own household. They are not the men who bring against the sweetest and the noblest examples of his lyric work their charges of pettiness or tameness, contraction or inadequacy; who taste a savour of corruption in “The Sisters” or a savour of effeminacy in “Boadicea.” They are the men who couple 34 “In Memoriam” with the Psalms of David as a work akin to these in scope and in effect; who compare the dramatic skill and subtle power to sound the depths of the human spirit displayed in “Maud” with the like display of these gifts in Hamlet and Othello. They are the men who would set his ode on the death of Wellington above Shelley’s lines on the death of Napoleon, his “Charge of the Light Brigade” beside Campbell’s “Battle of the Baltic” or Drayton’s “Battle of Agincourt,” the very poem whose model it follows afar off with such halting and unequal steps. They are the men who find in his collection of Arthurian idyls,—the Morte d’Albert as it might perhaps be more properly called, after the princely type to which (as he tells us with just pride) the poet has been fortunate enough to make his central figure so successfully conform,—an epic poem of profound and exalted morality. Upon this moral question I shall take leave to intercalate a few words. It does not appear to me that on the whole I need stand in fear of misapprehension or misrepresentation on one charge at least—that of envious or grudging reluctance to applaud the giver of any good gift for which all receivers should be glad to return thanks. I am not aware—but it is possible that this too maybe an instance of a man’s blindness to his own defects—of having by any overt or covert demonstration of so vile a spirit exposed my 35 name to be classed with the names, whether forged or genuine, of the rancorous and reptile crew of poeticules who decompose into criticasters; I do not remember to have ever as yet been driven by despair or hunger or malevolence to take up the trade of throwing dirt in the dark; nor am I conscious, at sight of my superiors, of an instant impulse to revile them. My first instinct, in such a case, is not the instinct of backbiting; I have even felt at such times some moderate sense of delight and admiration, and some slight pleasure in the attempt to express it loyally by such modest thanksgiving as I might. I hold myself therefore free to say what I think on this matter without fear of being taxed with the motives of a currish malignant. It seems to me that the moral tone of the Arthurian story has been on the whole lowered and degraded by Mr. Tennyson’s mode of treatment. Wishing to make his central figure the noble and perfect symbol of an ideal man, he has removed not merely the excuse but the explanation of the fatal and tragic loves of Launcelot and Guenevere. The hinge of the whole legend of the Round Table, from its first glory to its final fall, is the incestuous birth of Mordred from the connexion of Arthur with his half-sister, unknowing and unknown; as surely as the hinge of the Oresteia from first to last is the sacrifice at Aulis. From the immolation of Iphigenia springs the wrath of Clytæmnestra, 36 with all its train of evils ensuing; from the sin of Arthur’s youth proceeds the ruin of his reign and realm through the falsehood of his wife, a wife unloving and unloved. Remove in either case the plea which leaves the heroine less sinned against indeed than sinning, but yet not too base for tragic compassion and interest, and there remains merely the presentation of a vulgar adulteress. From the background of the one story the ignoble figure of Ægisthus starts into the foreground, and we see in place of the terrible and patient mother, perilous and piteous as a lioness bereaved, the congenial harlot of a coward and traitor. A poet undertaking to rewrite the Agamemnon, who should open his poem with some scene of dalliance or conspiracy between Ægisthus and Clytæmnestra and proceed to make of their common household intrigue the mainspring of his plan, would not more depress the design and lower the keynote of the Æschylean drama, than Mr. Tennyson has lowered the note and deformed the outline of the Arthurian story, by reducing Arthur to the level of a wittol, Guenevere to the level of a woman of intrigue, and Launcelot to the level of a “co-respondent.” Treated as he has treated it, the story is rather a case for the divorce-court than for poetry. At the utmost it might serve the recent censor of his countrymen, the champion of morals so dear to President Thiers and the virtuous journalist who draws a contrast 37 in favour of his chastity between him and other French or English authors, for a new study of the worn and wearisome old topic of domestic intrigue; but such “camelias” should be left to blow in the common hotbeds of the lower kind of novelist. Adultery must be tragic and exceptional to afford stuff for art to work upon; and the debased preference of Mr. Tennyson’s heroine for a lover so much beneath her noble and faithful husband is as mean an instance as any day can show in its newspaper reports of a common woman’s common sin. In the old story, the king, with the doom denounced in the beginning by Merlin hanging over all his toils and triumphs as a tragic shadow, stands apart in no undignified patience to await the end in its own good time of all his work and glory, with no eye for the pain and passion of the woman who sits beside him as queen rather than as wife. Such a figure is not unfit for the centre of a tragic action; it is neither ignoble nor inconceivable;but the besotted blindness of Mr. Tennyson’s “blameless king” to the treason of a woman who has had the first and last of his love and the whole devotion of his blameless life is nothing more or less than pitiful and ridiculous. All the studious care and exquisite eloquence of the poet can throw no genuine halo round the sprouting brows of a royal husband who remains to the very last the one man in his kingdom insensible of his disgrace. The 38 unclean taunt of the hateful Vivien is simply the expression in vile language of an undeniable truth; such a man as this king is indeed hardly “man at all;” either fool or coward he must surely be. Thus it is that by the very excision of what may have seemed in his eyes a moral blemish Mr. Tennyson has blemished the whole story; by the very exaltation of his hero as something more than man he has left him in the end something less. The keystone of the whole building is removed, and in place of a tragic house of song where even sin had all the dignity and beauty that sin can retain, and without which it can afford no fit material for tragedy, we find an incongruous edifice of tradition and invention where even virtue is made to seem either imbecile or vile. The story as it stood of old had in it something almost of Hellenic dignity and significance; in it as in the great Greek legends we could trace from a seemingly small root of evil the birth and growth of a calamitous fate, not sent by mere malevolence of heaven, yet in its awful weight and mystery of darkness apparently out of all due retributive proportion to the careless sin or folly of presumptuous weakness which first incurred its infliction; so that by mere hasty resistance and return of violence for violence a noble man may unwittingly bring on himself and all his house the curse denounced on parricide, by mere casual indulgence of light love and passing wantonness a hero king may 39 unknowingly bring on himself and all his kingdom the doom imposed on incest. This presence and imminence of Ate inevitable as invisible throughout the tragic course of action can alone confer on such a story the proper significance and the necessary dignity; without it the action would want meaning and the passion would want nobility; with it, we may hear in the high funereal homily which concludes as with dirge-music the great old book of Sir Thomas Mallory some echo not utterly unworthy of that supreme lament of wondering and wailing spirits— |

|

|

The fatal consequence or corollary of this original flaw in his scheme is that the modern poet has been obliged to degrade all the other figures of the legend in order to bring them into due harmony with the degraded figures of Arthur and Guenevere. The courteous and loyal Gawain of the old romancers, already deformed and maligned in the version of Mallory himself, is here a vulgar traitor; the benignant Lady of the Lake, foster-mother of Launcelot, redeemer and comforter of Pelleas, becomes the very vilest figure in all that cycle of more or less symbolic agents and patients which Mr. Tennyson has set revolving round the figure of his central wittol. I certainly do not share the objection of the virtuous journalist to the presentation in art of 40 an unchaste woman; but I certainly desire that the creature presented should retain some trace of human or if need be of devilish dignity. The Vivien of Mr. Tennyson’s idyl seems to me, to speak frankly, about the most base and repulsive person ever set forth in serious literature. Her impurity is actually eclipsed by her incredible and incomparable vulgarity—(“O ay,” said Vivien, “that were likely too”). She is such a sordid creature as plucks men passing by the sleeve. I am of course aware that this figure appears the very type and model of a beautiful and fearful temptress of the flesh, the very embodied and ennobled ideal of danger and desire, in the chaster eyes of the virtuous journalist who grows sick with horror and disgust at the license of other French and English writers; but I have yet to find the French or English contemporary poem containing a passage that can be matched against the loathsome dialogue in which Merlin and Vivien discuss the nightly transgressions against chastity, within doors and without, of the various knights of' Arthur’s court. I do not remember that any modern poet whose fame has been assailed on the score of sensual immorality—say for instance the author of “Mademoiselle de Maupin” or the author of the “Fleurs du Mal”—has ever devoted an elaborate poem to describing the erotic fluctuations and vacillations of a dotard under the moral and physical manipulaton of a prostitute. The conversation 41 of Vivien is exactly described in the poet’s own phrase—it is “as the poached filth that floods the middle street.” Nothing like it can be cited from the verse which embodies other poetic personations of unchaste women. From the Cleopatra of Shakespeare and the Dalilah of Milton to the Phraxanor of Wells, a figure worthy to be ranked not far in design below the highest of theirs, we may pass without fear of finding any such pollution. Those heroines of sin are evil, but noble in their evil way; it is the utterly ignoble quality of Vivien which makes her so unspeakably repulsive and unfit for artistic treatment. “Smiling saucily,” she is simply a subject for the police-court. The “Femmes Damnées” of Baudelaire may be worthier of hell-fire than a common harlot like this, but that side of their passion which would render them amenable to the notice of the nearest station is not what is kept before us throughout that condemned poem; it is an infinite perverse refinement, an infinite reverse aspiration, “the end of which things is death;” and from the barren places of unsexed desire the tragic lyrist points them at last along their downward way to the land of sleepless winds and scourging storms, where the shadows of things perverted shall toss and turn for ever in a Dantesque cycle and agony of changeless change; a lyric close of bitter tempest and deep wide music of lost souls, not inaptly described by M. Asselineau 42 as a “fulgurant” harmony after the fashion of Beethoven. The slight sketch in eight lines of Matha in “Ratbert” resumes all the imaginable horror and loveliness of a wicked and beautiful woman; but Hugo does not make her open her lips to let out the foul talk or the “saucy” smile of the common street. “La blonde fauve,” all but naked among the piled-up roses, with feet dabbled in blood, and the laughter of hell itself on her rose-red mouth, is as horrible as any proper object of art can be; but she is not vile and intolerable as Vivien. I do not fear or hesitate to say on this occasion what I think and have always thought on this matter; for I trust to have shown before now that the poet in the sunshine of whose noble genius the men of my generation grew up and took delight has no more ardent or more loyal admirer than myself among the herd of imitative parasites and thievish satellites who grovel at his heels; that I need feel no apprehension of being placed “in the rank of verminous fellows” who let themselves out to lie for hatred or for hire—“qui quæstum non corporis sed animi sui faciunt,” as Major Dalgetty might have defined them. Among these obscene vermin I do not hold myself liable to be classed; though I may be unworthy to express, however capable of feeling, the same abhorrence as the Quarterly reviewer of “Vivien” for the exhibition of the libidinous infirmity of unvenerable age. But these are not the grounds on which 43 Mr. Austin objects to the ethical tendency of Mr. Tennyson’s poetry. His complaint against all those of his countrymen who spend their time in writing verse is that their verse is devoted to the worship of “woman, woman, woman, woman.” He “hardly likes to own sex with” a man who devotes his life to the love of a woman, and is ready to lay down his life and to sacrifice his soul for the chance of preserving her reputation. It is probable that the reluctance would be cordially reciprocated. A writer about as much beneath Mr. Austin as Mr. Austin is beneath the main objects of his attack has charged certain poetry of the present day with constant and distasteful recurrence of devotion to “some person of the other sex.” It is at least significant that this person should have come forward, for once under his own name, to vindicate the moral worth of Petronius Arbiter; a writer, I believe, whose especial weakness (as exhibited in the characters of his book) was not a “hankering” after persons “of the other sex.” It is as well to remember where we may be when we find ourselves in the company of these anti-sexual moralists. _____ * In Dr. Burroughs’ excellent little book there is a fault common to almost all champions of his great friend; they will treat Whitman as “Athanasius contra mundum:” they will assume that if he be right all other poets must be wrong; and if this intimation were confined to America there might be some plausible reason to admit it; but if we pass beyond and have to choose between Whitman and the world, we must regretfully drop the “Leaves of Grass” and retain at least for example the “Légende des Siècles.” As to this matter of rhythm and rhyme, prose and verse, I find in this little essay some things which out of pure regard and sympathy I could wish away, and consigned to the more congenial page of some tenth-rate poeticule worn out with failure after failure, and now squat in his hole like the tailless fox he is, curled up to snarl and whimper beneath the inaccessible vine of song. Let me suggest that it may not be observed in the grand literary relics of nations that their best poetry has always, or has ever, adopted essentially the prose form, preserving interior rhythm only. I do not “ask dulcet rhymes from” Whitman; I far prefer his rhythms to any merely “dulcet metres;” I would have him in nowise other than he is; but I certainly do not wish to see his form or style reproduced at second-hand by a school of disciples with less deep and exalted sense of rhythm. As to rhyme, there is some rhymed verse that holds more music, carries more weight, flies higher and wider in equal scope of sense and sound, than all but the highest human speech has ever done; and would have done no more, as no verse has done more, had it been unrhymed; witness the song of the Earth from Shelley’s “Prometheus Unbound.” Do as well without rhyme if you can, or do as well with rhyme, it is of no moment whatever; a thing not noticeable or perceptible except by pedants and sciolists; in either case your triumph will be equal. In a precious and memorable excerpt given by Dr. Burroughs from some article in the North American Review, the writer, a German by his name, after much gabble against prosody, observes with triumph as a final instance of the progress of language that “the spiritualizing and enfranchising influence of Christianity transformed Greek into an accentuated language.” The present poets of Greece, I presume, know better than to waste their genius on the same ridiculous elaborations of corresponsive metre which occupied the pagan and benighted intellects of Æschylus and Pindar. I have heard before now of many deliverances wrought by Christianity; but I had never yet perceived that among the most remarkable of these—“an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace”—was to be reckoned the transformation of the language spoken under Pericles into the language spoken under King Otho and King George. _____ 49 What is true of all poets is among them all most markedly true of Whitman, that his manner and his matter grow together; that where you catch a note of discord there you will find something wrong inly, the natural source of that outer wrongdoing; wherever you catch a note of good music you will surely find that it came whence only it could come, from some true root of music in the thought or thing spoken. There never was and will never be a poet who had verbal harmony and nothing else; if there was 50 in him no inner depth or strength or truth, then that which men took for music in his mere speech was no such thing as music. _____ * I cannot help calling just now to mind an epigram—very rude, after the fashion of the time, but here certainly not impertinent but pertinent—cited by Boswell on a quarrel between two “beaux;” the second stanza runs thus, with one word altered of necessity, as that quarrel was not on poetry but on religion:— “Peace, coxcombs, peace! and both agree; _____ “Their little hands were never made 56 Their little hands—can it be necessary to remind them?—were made to throw dirt and stones with impunity at passers- by of a different kind. This is their usual business, and they do it with a will; though (to drop metaphor for awhile) we may concede that English reviewers—and among them the reviewer of the “Spectator”—have not always been unready to do accurate justice to the genuine worth of new American writers; among much poor patchwork of comic and serious stuff, which shared their welcome and diminished its worth, they have yet found some fit word of praise for the true pathos of Bret Harte, the true passion of Joaquin Miller. But the men really and naturally dear to them are the literators of Boston; truly, and in no good sense, the school of New England—Britannia pejor; a land of dissonant reverberations and distorted reflections from our own.* _____ * Not that the British worshipper gets much tolerance for his countrymen in return. In an eloquent essay on the insolence of Englishmen towards Americans, for which doubtless there are but too good grounds, Mr. Lowell shows himself as sore as a whipped cutpurse of the days “ere carts had lost their tails” under the vulgar imputation of vulgarity. It is doubtless a very gross charge, and one often flung at Americans by English lackeys and bullies of the vulgarest order. Is there ever any ground for it discernible in the dainty culture of overbred letters which, as we hear, distinguishes New England? I remember to have read a passage from certain notes of travel in Italy published by an eminent and eloquent writer—that I could but remember his name and grace my page with it!—who after some just remarks on Byron’s absurd and famous description of a waterfall, proceeds to observe that Milton was the only poet who ever made real poetry out of a cataract—“AND THAT WAS IN HIS EYE.” _____

Under The Microscope - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

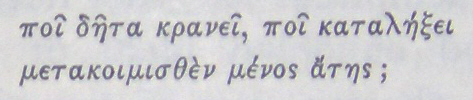

|