ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{North Coast and other Poems 1867}

178 (NORTH COAST, 18—.)

I. ON THE HILLSIDE.

SO still he sat upon the mountain-side, So still and gray, the rainy light played on him, So still, the ancient sheep-dog at his feet |

|

|

So still, he noted not the dreamy stranger, This old man’s heart was not on the hill-side, 180 He could not see the flowing of the shadows, Shouting afar off to the mountain echoes; His eyes were fixed upon the still vale lying And yet these things he saw not, but saw visions: And down the dale the kilted huntsman, standing Yea, all the things he heard were visions also,— 181 So still, so still, he sat in meditation, And neither knew his eyes were moist and dim, Till, setting hand upon the old man’s shoulder, When, looking up under his twitching eyelids, A face familiar with the wind and water, And long and wearily, with querulous wonder 182 ‘Know you!’ the stranger echoed, laughing sadly; ‘Am I so changed with piping tunes to Fortune, ‘Does the first face I meet, returning homeward, Then as one smitten sudden by a sunbeam, And gripped the strong hand with his feeble fingers, ‘Why, see!’ cried Hector, while the hound smelt round him, 183 ‘He knows his ancient playmate on these hills; Then for a space the eyes of Adam Hart ‘Hector! alive!—a wraith among the wraiths ‘Welcome!—and yet how can I give you welcome? ‘I am the grave of him you knew. At times ‘Useless and feeble, here I linger yet, 184 ‘Yet welcome, welcome to a weary place, ‘Ay, Adam,’ Hector answered, bitterly, ‘Yet fear not; nothing now can quite appal me; Clear were his accents as the plover’s crying, And Adam knew the thing he dared not ask, ‘Nay, but they live!’ he cried, and gripped the arm 185 Then tears came, which the strong man dashed aside, And for a moment like a broken reed Saying, ‘GOD has not lied upon the waters! ‘Oh, dawn by dawn rose up across the greenness ‘And not a star by night but said they lived; ‘And in the smooth sea, over shipboard leaning, 186 |

|

|

‘And the sails’ creaking overhead at night ‘Was full of Highland sounds; and when I trode ‘It is enough, I say, to know they live; 187 Stilly the old man listened; his dim eyes His dim eye flamed under his wrinkled forehead, ‘Better be foul with dust, be food for worms, ‘I say there is no refuge from these things, Then, as the black wind passes from a lake, ‘Heaven help us all, alas, we need some help! 188 ‘Ay, and such murder were less black, I swear, ‘The draining of the heart’s blood drop by drop, ‘O Hector, where the little children came ‘And where the Highland lassie drew her water, ‘And where the old gray men and snooded matrons |

|

|

‘And bloody heather grows upon the threshold, ‘And yet the clouds pass, and the sun is shining, 190 And Hector answered not, but cast around him And neither spake again. The old man gripped While Hector Stuart followed, with his eyes Sweet was the air, that afternoon of autumn, Westward, between the hills, the sinking sun |

|

|

While overhead the blue west turned to amber, Nearer, on either hand, arose the hills, 192 The boulder gray in sunset, and, still nearer, And as the sunlight travelled on the hill-side, And from their track the clumsy partridge flew, It was a scene that seemed at peace with GOD, Save the breeze breathing, and that half-heard murmur Not yet at peace with that sweet stillness throbbed 193 And Adam looked not around him as he walked, Blown in his eyes by the moist mountain breeze; But Hector Stuart looked toward the ocean, From mossy ridge to ridge they passed in silence, Then on by rocky paths they journeyed slowly, Here, pausing, Adam pointed through the twilight, 194 |

|

|

Only at intervals the dim black square, And here and there among the growing grass And on the sun-side of a little hillock 195 Then Hector stood upon the threshold-stone, ‘Why, on this very place my mother sat, ‘Desolate, desolate, all desolate! ‘I cannot hunger on in silence longer— So speaking, he distinguished in the twilight |

|

|

And on the roof grew slimy grass and weeds, ‘Enter,’ said Adam Hart, ‘and you shall hear ‘And here this night take shelter, if you will, 197 THE KIRKYARD OF GLEN OONA.

LIKE one whose spirit evil dreams have troubled, And, rolling wild eyes round the dusky chamber, ‘You have slept sound,’ said Adam, stooping o’er him. ‘But I have dreamt—GOD keep me from such dreams! ‘The women’s shrieks are in my ears I feel 198 |

|

|

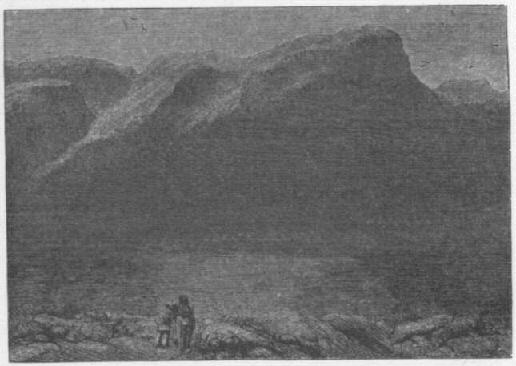

Then, rising up, he drew his plaid around him, And, drinking in the air with swelling nostrils, While, overhead, the lift from gray to blue 199 ‘Desolate! desolate!’ he cried aloud, ‘But, cold and gray, dawn drops into the silence, Then Adam called him in, and set before him And when the meal was over, Adam took Northward they turned, and ankle-deep in dew, Whence issuing, they came upon the brink 200 There all was silent as a dead man’s heart, While the dark water shimmered, and thin waves Then Hector crossed himself, and shivered, saying, ‘’T is stiller than the frozen seas; ’t is drearer Even as he spake, dead silentness was broken ‘Hark!’ cried the old man, and the sound grew clearer, 201 |

|

|

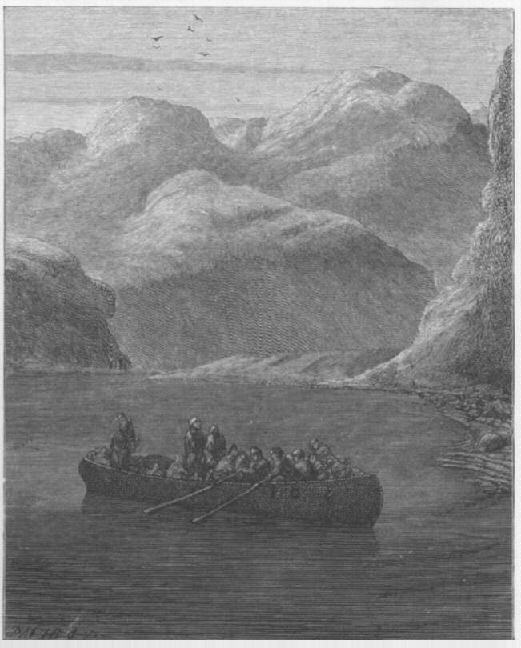

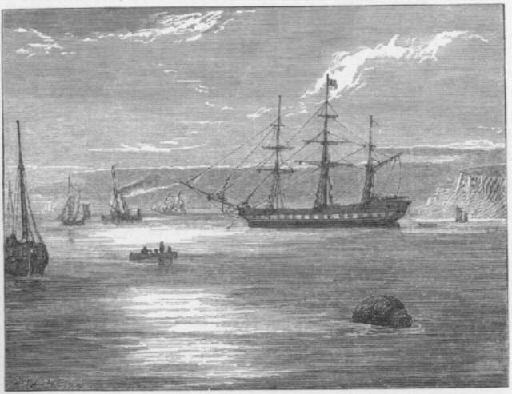

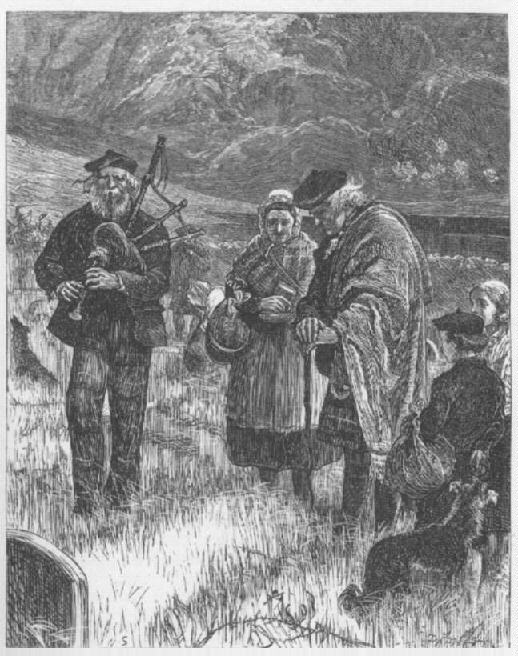

And clearer grew the music, till, at last, ‘The pipes!’ cried Hector, holding up his hand Even like a ghostly melody by spirits 202 Behind the horizon of our mutual sorrows, While the day grew, and still the rain was shaken Showing the stony peaks and alps untrodden, Then sunrise, glistening faintly o’er the peaks, In the mid-water, moving very slowly, And clearer, louder, from the boat was wafted 203 |

|

|

And as the boat drew nearer, and the music The boatmen hanging heads and pulling slow, 204 And stretched along the stern a silent shape, And at its head the Piper stood erect, Then Adam raised the bonnet from his brow, ‘I have no tear for him, the blesséd dead; How shall they sleep in peace apart from dust |

|

|

‘Better have stabbed with bloody huntsman’s knife ‘Then had their end been sweeter, for their eyes 206 And nearer yet and nearer came the boat, And those who sat within the boat were plainer, But most were very old, yea, ancient men, And some were crooning in a thin low voice Dwelt as a misty trouble; and a few |

|

|

Then, quickening oars, the rowers ran the boat Old women leaning on their weeping daughters, 208 And one there was, old, old, who could not see, ‘Follow!’ said Adam, while the mourners wended And they who watched were ’ware of others coming And, while the gray old piper led the mourners, Till hill, and vale, and water rang, and voices And Hector Stuart, following Adam Hart, 209 |

|

|

A desolate place, where rough graves, rudely heapen, And there around an open tomb they gathered, Till, his voice ceasing, once again the pipes 210 Then Adam whispered, ‘Blest is he they bury! ‘And all these souls will gather on her decks, Silent they stood, each gazing on the dust It was a sight that withered up the heart, To mark the woe of women, and the heartache |

|

|

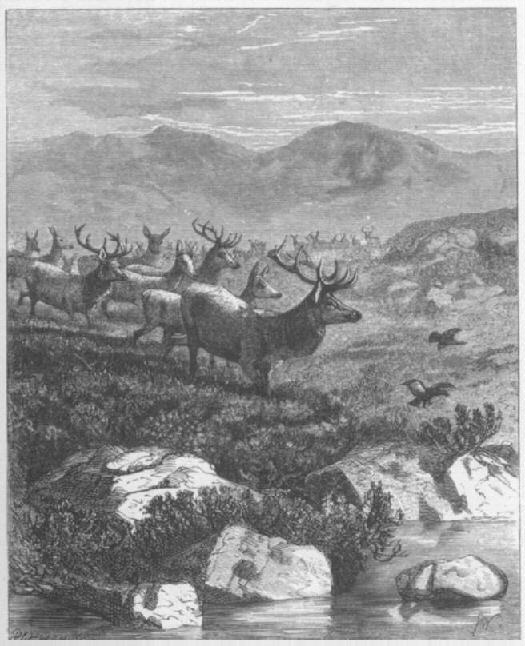

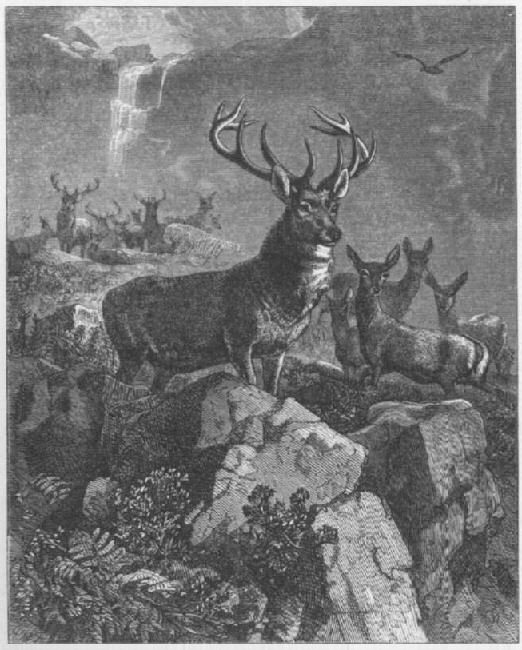

Then one cried, ‘GOD, my GOD, I want to die! And then another answered, ‘He knows best! 212 And yet another said, ‘Our bairns are young, ‘This is the glen where wife and I were born, And at his words, his wife, an ancient dame, Then once again the priest brake out in prayer, And on a steep crag, overhead, behold! |

|

|

And, while behind him followed harts and hinds, Then vanished as a mist, with all his people, 214 Lochaber! and Lochaber! and Lochaber! _____

North Coast and other Poems continued or back to North Coast and other Poems - Contents

|

|

|

|

|

|

|