ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (12)

The Book of Orm (1870) - continued |

|

|

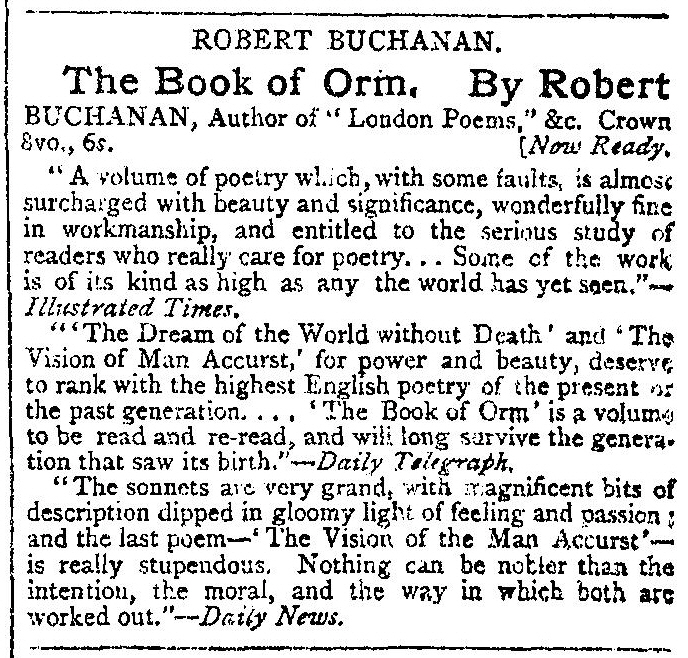

[Advert from The Graphic (30 July, 1870).]

The North British Review (July, 1870) CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE. ..... 49. The Book of Orm: A Prelude to the Epic. By Robert Buchanan. (London: Strahan.) ..... 49. MR. BUCHANAN has attempted many kinds of poetry, never without success, but never with perfect mastery. For he has great energy, pathos, and command of language; and the aspects of nature and the problems of the time move him deeply, indeed too deeply. The incompleteness of his genius is apparent in the fact that he has had no imitators; for imitation is an attempt to reproduce that fascinating and unmistakeable novelty of music which every new master of poetry possesses, and which Mr. Buchanan distinctly lacks. The motive of the best of his former poems, “Meg Blaine” and “London Lyrics,” is a deeply-felt sense of the misery of the poor. It may be doubted whether this feeling, however, earnest and passionate, can ever result in true poetry, except when it awakens the lyric cry in some one of the actual sufferers, when it finds utterance in the spontaneous ballad verse of which some fragments remain from the popular wretchedness of the later middle ages. In his present volume Mr. Buchanan deserts the subject which he once thought it his mission to win into the realm of art for that of the general misery of life. Orm is a Celtic singer, born in the evening of the world; and The Book of Orm is a record of visions seen through the mixed lights and melancholy vapours of Loch Coruisk. Here, like Obermann among fairer mountains, Orm broods on the great ultimate questions of life; but the harsh expression of his despair differs from the gentler melancholy of Senancour, as the meres and crags of Skye differ from the heights and lakes of Switzerland. The great blot of the book, indeed, is that it is too harsh and bitter in spirit; that the emotions it exhibits—those of religious longing turning with words of despair and anger on the God it cannot find—are unfit for poetic expression. Orm’s soul is described as “a Wind and the description is true of the matter and tone of the book. The Celtic seer is seeking for a sign; and, like many of the modern poets who choose religious subjects, he seeks with all the confidence, and none of the success of Lord Herbert of Cherbury. “Lift up thine eyes, old man, and look on me; In the “Songs of Corruption” the Sage is reconciled to the common ordinances of decay and death, by a vision in which the bodies of the dead seem no longer to remain and be mingled with the earth, but vanish suddenly with the vanishing of life:— “And men and women feared the earth behind them; The “Lifting of the Veil,” in like manner, consoles him for the absence of the sign he had so eagerly desired, by showing what would be the effects of the constant and open presence of the Beatific Vision. The continual splendour petrifies all life and action; and in the details of this vision Mr. Buchanan appears at his best. “Hard by I noted But one I noted, What connection there may be between the calm of the Sage when he wakens and finds that this strange time was but a dream, and the forced misotheism of the succeeding Coruisken sonnets, it is not easy to see. In these unfortunate verses Mr. Buchanan has exceeded the irreverence, while he has none of the fiery and fitful music, of the choruses in Atalanta in Calydon. If the Palinode of the twenty-ninth sonnet has any sincerity, those entitled “God is Pitiless” and “Could God be Judged” are doubly convicted of being insincere. This assumed Titanism, the affectation of struggle and reconciliation with Destiny, is an offence to the quiet and dignity of poetry. Mr. Buchanan might remember with advantage the words of Althæa in the play which seems so powerfully to have affected him: “Small praise gets man dispraising the high Gods.” In the sonnets “What Spirit Cometh” and “Stay, O Spirit,” he shows what he can do on the ground of human affections and natural pathos. These he deserts again in the poems called “The Devil’s Mystics,” of which all that need be said is that they contain, among much obscurity, reflections of the thought of Clough and Blake. Better things may be looked for from Mr. Buchanan when he returns, in a happier spirit, to the subjects he has by previous treatment made peculiarly his own. 50. MR. ROSSETTI’S Poems have the unwonted and personal qualities of all really original work. The sense of strangeness is soon lost in admiration of the great beauty of the verses, of their wide range of subject, their various and appropriate music, their lyric fire, their lofty tone, and their high level of common perfection. This perfection becomes almost a difficulty to the critic. For there are scarcely any failures to be set against successes; and the slightest songs are as complete in thought, as elaborate in art, as fitly set to their appropriate melody, as the sonnets or the tragic ballads. “Sweet dimness of her loosened hair’s downfall The grief that dwells in this House of Life is not less gracious than the love; it is more patient than hopeful, saddened and soothed with memory, and does “with symbols play” of Christian art. The keynote of many poems is struck in the beautiful preluding verses of “The Blessed Damozel.” There all that it has not entered into the mind of man to conceive, of the joy prepared for tried and reunited lovers, is set forth in figures which recall the early grace of Raphael, and the pure colour of Angelico. But in “The Blessed Damozel” there is more of the glow and movement of real life than in Angelico’s art. Hers is not a painless sympathy with pain”:— “She cast her arms along The song of “The Woodspurge” depicts another mood of sorrow, newborn, and scarcely realized, the dull continual pain of a soul shaken from its harmony by stress of the bitter passion whose will is like the wind’s will:— “The wind flapped loose, the wind was still, Between my knees my forehead was,— My eyes, wide open, had the run From perfect grief there need not be Apart from the main stream of personal emotions are the five poems “Jenny,” “Sister Helen,” “Edenbower,” “The Burden of Nineveh,” and a “Last Confession,” which show the dramatic side of Mr. Rossetti’s genius. Of “Jenny” it may be said that the beauty of modern life, its melancholy, doubt, self-questioning, sad pleasures, and extremes of luxury and wretchedness, have never been more finely treated by poets who find in modern life the only proper subject of modern art; nor has any one of the many authors who have been attracted by the “splendours and miseries of courtezans” seen more clearly “the pity of it,” and the hopelessness:— “What if to her all this were said? The necessarily painful character of this poem is relieved by the image of the “rose shut in a book, in which pure women may not look,” as the tragic weight of “A Last Confession” is lightened by the gaiety and charm of the Italian song, and the picture of the loveliness of the girl “whose dark lashes evermore The transition from “Jenny” to “Sister Helen” proves, in its abruptness, the versatility of Mr. Rossetti’s genius. In this ballad the depth of sorrow of “the Bonny Hind” and the weirdness of superstition of “the Lykewake Dirge” meet and give each other force and gloom. As in a tragic rendering of the Theocritean idyl, the spells of a revengeful leman bring back the soul of her treacherous lover to the “far abode” where it shall never be severed from the soul of its victim and destroyer. “Edenbower” again, the strange music of which seems to glow with the litheness and life of the most subtle of the beats of the field, is the song of vengeance of the serpent bride of Adam. The power shown in it of adapting music to subject is again displayed in “the Burden of Nineveh,” perhaps the most thoughtful of Mr. Rossetti’s poems. “The empty pastures blind with rain” or, “At Iglio, in the first thin shade o’ the hills.” As a rule, he reads his own emotions into the outward world, as in “The Woodspurge,” or people nature with gracious forms of love, “and many a shape whose name not itself knoweth.” Here, and always, he is a poet of the school of art; and it may be believed that his very highest merits, the personality of a genius only satisfied with artistic perfection, will prove the greatest bar to his general acceptance. ___

The London Quarterly (July, 1870) Glaphyra, and Other Poems. By Francis Reynolds, Author of “Alice Rushton, and Other Poems.” London: Longmans. 1870. THAT the present age, viewed on one side, is materialistic and utilitarian, cannot be doubted. Nevertheless, there has seldom been an age in any country in which the springs of poetry were fuller or more frequent; or the forms of poetry more fresh, and various, and original. Here are Robert Buchanan and Gerald Massey, both of them exuberant as well as genuine, and often very beautiful, poets, sending forth each a new volume. Here is Mr. Reynolds, a name as yet but little known, but which will undoubtedly take a place among the poets of rarer culture and of higher mark. Here is Mr. Locker, in a style, it is true, redolent of city-life, and far removed from the sphere of either of the other poets, but in a vein, notwithstanding, of genuine minstrelsy, putting forth vers de société which may almost rank with those of Praed. “I love thee, Autumn; whether, rude and loud, Buchanan’s Book of Orm has been written, as appears from a note of the author’s, whilst ill-health has weighed upon him. This has prevented the volume from being published in a complete form. “A Rune Found in the Starlight,” “The Songs of Heaven,” are written, but cannot, in Mr. Buchanan’s present state of health, “be made perfect for press.” “The all-important ‘Devil’s Dirge,’” also, we are informed, is wanting in the present edition. “Now an evangel The wild “Tale of Eternity” will not add to the fame of Gerald Massey, whose dreams as to eternity and the eternal world, by the way, are very different indeed in their character from those of Buchanan. But the “Carmina Nuptialia,” and the other parts of the volume, are full of the characteristic beauties of Mr. Massey, whose gift (and he has a rare and precious gift) is that of a lyrist. We think we have seen the poem on the late Mr. Thackeray somewhere before, but we are sorry that our limits forbid us to print here lines so true, so touching, so altogether admirable. ___

The Nation (4 August, 1870 - Vol. 11, No. 266, pp. 76-77) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S NEW BOOK.* IN previous volumes, M. Buchanan has published verses which were not precisely good poetry, and which were not very agreeable reading, but which, nevertheless, showed that he had in him something of poetic power. The imagination in them was of the purely sympathetic order, and was unaccompanied by any but a weak and futile way of thinking, and was unaccompanied, too, so far as appeared, by any perception of the beautiful or sense of the humorous. The impression given was of a thoroughly Scotch mind and nature, flushed with a good deal of that hectic which has consigned a great many young Scotchmen to poetry and an early grave. But for all that—though he was conceited and bumptious, pragmatic, unideal, of unrefined taste, not well educated in the higher sense of the word, nor perhaps in the lower—he nevertheless had the genuine insight which sympathy gives into the sufferings and joys, but especially into the sufferings, of certain of the humbler of his fellow-creatures, and he was able to express it in a form that made it effective upon others. A consumptive artisan in an alley pining for green fields; a prostitute in her chamber, with a heart hardened but sore and sick; a fisher-wife, deserted by her seducer; an old couple who lament in their cottage the loss of the son that was to be a scholar—people like these Mr. Buchanan gives us, or used to give us, with real power. It was not, one thought, a very good choice of subjects; but it was, one saw by many signs, a wise enough choice if the man who made it was to do his best, or was to do anything worth while in literature. Nor was it absolutely bad either; if not the best, it was still not bad, and many of the poems produced when our author was working this vein are of value and capable of giving pleasure. “There is a mortal, and his name is Orm, “And he is aged early, in a time “O brother, hold me by the hand, and hearken, “Thou wert born yesterday, but thou art old, This dismal prelude is the appropriate antechamber to the poems that follow; but perhaps better as showing more clearly the unhealthy frame of mind in which the book was planned, and as foreshadowing the pretentious feebleness of it, is the affected and melancholic “inscription:” “Flowers pluckt upon a grave by moonlight, pale “If one of these poor flowers be worthy thee, “Pray for me, Comrade! Close to thee I creep, “If Love will serve, lo! how I love my Friend— “Now, as thou risest gently from thy knees, We had supposed the fashion had gone out of being publicly sad-eyed and ruined in hopes. It is going out certainly, if it has not quite gone, and this performance of Mr. Buchanan’s will help it to its burial. Nothing could well be in worse taste. “In the beginning, and hid The Face. When The Face is pressed closest to The Veil the heavens are bright, and when it is withdrawn they darken: “But when, grown weary that is to say, the stars. Equally imaginative and coherent with this account of day and night, and the way in which Nature interposes between man and the maker of the universe, is Mr. Buchanan’s conception—to call it so—of the way in which Nature first fell into her present condition of giving dumb intimations, as it were, but no full revelation of God: “For oft, in the beginning, long ago, We have given our guess at the interpretation to be given the author in this first poem. But it is like guessing at the interpretation of a jumbled, bald dream; the thing needs an interpreter; but when you have got it, the interpretation is nothing. “On the high path where few men fare, namely, of his own shadow, with which Orm endeavors to impress on us awe and fear. Precisely the emotions which, as a matter of fact, agitate the breast of the reader while he goes through this piece, we would rather not state. He will, however, find some pretty descriptions of scenery amid much rubbish about the rainbow, which does duty as a bridge, by way of which Orm, with his usual happiness of invention, makes the spirit of the Hoary One pass into heaven. The “Songs of Corruption” which follow “The Man and the Shadow” are much the same in character as their predecessors, but not quite so devoid of merit. They get their name from having been written, or because supposed to have been written, by Orm in a lonely graveyard, and because, too, of their being in subject appropriate to such a place of meditation. Then we have a lonely interview that Orm has with Satan, whom and whose works Orm defies. The old style of conversation is still in use at these ceremonies, it seems: “SPIRIT. Thou knowest me now. ORM. I know thee! SPIRIT. And thy cheek ORM. Nay, by pride, and by despair, After much discussion the dawn breaks, Satan departs with a request that Orm pray for him and for all “Strong spirits that are outcast;” and Orm declares that evil is not disguised good, but is evil. * “The Book of Orm. A Prelude to the Epic. By Robert Buchanan.” New York: Geo. Routledge & Sons. 1870. ___

The Echo (5 August, 1870 - p.2) The Book of Orm, by Robert Buchanan (Strahan and Co.).—We cannot say that Mr. Buchanan’s last work appears to us an advance on his previous volumes. It is very clever—sometimes something more; and the “Vision of the Man Accurst”—but for a certain diffuseness and mistiness in parts—would have been really a remarkable poem. But the general impression which the book produces is that of laboured effort, coupled with an autocratic tone which is more or less audible in all Mr. Buchanan’s utterances, and which is the perhaps pardonable fault of a young man. In the “Book of Orm” he comes somewhat too ostentatiously forward to settle once and for ever the greatest mysteries of life; and such sonnets as that entitled “Could God be Judged” betray a self-conscious effort to be bold and striking which is out of place, when we consider the subject. The finest example of human self-assertion which we know is the celebrated quatrain of David Elginbrod, and much in the “Book of Orm” seems to us a windy expansion of that terse and memorable epigram. Mr. Buchanan, with Mr. Matthew Arnold, believes in the Celt; but, whereas Mr. Arnold expects much from the Celt’s leaven of mysticism and imagination, Mr. Buchanan also expects him to conquer the world. “The world’s great future rests with thee,” he says; and, if this be true, we hope the Celt will lose no time in setting about the task, for at present it looks as though the world were crushing the Celt into remote corners, and slowly obliterating him. We should do great injustice to the “Book of Orm,” however, if we omitted to mention that it contains several very finely imaginative passages; and we are bound, besides, to make allowances for the absence of what the author tells us is an “all-important” part of it. Mr. Buchanan, this book informs us, is engaged on an epic. A more modest poet would have published the book, and left others to judge of its epic qualities. ___

The Illustrated London News (3 September, 1870 - p.26) The Book of Orm. By Robert Buchanan. (Strahan and Co.) The author has by common consent been placed high amongst our modern bards, and this volume will tend to confirm his position so far as his intellectual gifts and his mastery of the mechanical appliances peculiar to his craft are concerned. It is not everybody, however, who can assume the frame of mind required for the proper appreciation of sombre, mystic, enigmatical poetry; and if this volume should become popular, it will show that morbid, melancholy, ghostly feelings and yearnings are more common than one would have supposed amongst our practical population. A perusal of the pages begets such a condition of spirit as might be engendered by a twilight stroll in a beautiful churchyard or a solitary ramble through a fine ruin with a reputation for being haunted. No doubt a certain elevation and chastening of soul may be thus attained; but there is a contemporaneous depression of vital energy and slackness of the nervous system. ___

The Guardian (5 October, 1870) [Note: Another review in which The Book of Orm was compared unfavorably with Rossetti’s Poems. I have included the final paragraph of the Rossetti review, but the full version is available here.] Reviews. Poems. By DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI. Ellis. ... We might search long either in book or memory for a poem which excels this little song in touching our sense of mystery without departing far from the sights and sounds of ordinary earth. Mr. Rossetti’s volume affords many more striking specimens of his power as a poet; but nothing, perhaps, which bears a sharper and more distinctive impress. We have here his simplicity of manner, his directness of expression, his sensibility to impressions from without, and that peculiar skill in blending facts of sense with each other which gives tone, keeping, and moderation to his treatment of the harmonies of thought. The still sad music of humanity, There are times at which society is better than solitude, and the soft warmth of the lowland valley more favourable to health of body and mind than the chilly and austere desolation of the mountain-top. Or if Mr. Buchanan is obliged to move among the solitary peaks of thought, he would, if we are not mistaken, employ himself at present more wisely in drawing, petal by petal, some of the flowers that bloom in the crevices of the rock, than in trying to climb higher and higher at the risk of injurious tension of limb and lung. The work of life, we know, must be done; and we should be sorry to discourage Mr. Buchanan in his course of habitual literary activity. But it is seldom or never a matter of plain duty to write an epic; and Mr. Buchanan had better abstain from proceeding with such a task till his nerves are more firmly strung, his strength re-established, his command of form more complete, and his thoughts and feelings in a state more capable of satisfactory condensation. Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or The Book of Orm. _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued Napoleon Fallen (1871)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|