|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS

29. Clarissa (1890) - continued

The Graphic (15 February, 1890)

THEATRES.

MR. BUCHANAN’S Clarissa, at the VAUDEVILLE, is necessarily a work of more sombre and less varied complexion than the same writer’s adaptations of “Tom Jones” and “Joseph Andrews.” Unless the whole spirit and moral of Richardson’s novel were to be falsified, it was inevitable that this “history of a young lady” should present a more or less monstrous picture of villany fertile in odious devices for undermining female honour. The tragic ending, with the death of one who, “though wrapped in a strange cloud of crime and shame,” lived, like Shelley’s heroine, “ever holy and unstained,” could not indeed by any effort of ingenuity be dispensed with. Mr. Buchanan has incurred censure for making Clarissa, at the last moment, embrace the dying Lovelace, and, no doubt, there is something offensive in the notion of her lips being polluted by contact with those of this coarse and brutal type of the man de bonnes fortunes of the Richardson period; but Mr. Buchanan has taken occasion to protest that this is only the act of one whose consciousness of what is passing around her has faded into a dream of death. The concession that has really been made to the supposed craving of playgoers for romantic endings lies in the notion of inspiring Lovelace at the last moment with a disinterested love for his victim which such a man could not possibly feel. This is a notion borrowed from the French piece, of which Mr. Buchanan acknowledges in the play bill that he has made “free use.” It is not Richardson, nor is it in Richardson’s vein, but the wonderful fact is that the adaptor has, after all, and in spite of the new incidents, and even new characters, he has introduced, given us a play that approaches so nearly to a faithful presentation both of the story and the spirit of the old novel. The stage management has been well thought out; and the performance generally is characterised by harmony and finish. The most disappointing item is the Lovelace of Mr. Thalberg, who, though physically well endowed for the part, puts on, like Rosalind, “a swashing and a martial outside,” and indulges in extravagant postures and wavings of the arms, which have nothing in common with the seductive fine gentleman of the period of wigs and swords. Miss Winifred Emery’s Clarissa is, on the other hand, perfect in its grace, tenderness, resignation, and strength of character. For the special behoof of Mr. Thomas Thorne the author has invented a character compounded of the attributes of Belford, Tomlinson, and Morden—a broken-down, dissipated tool of Lovelace, who, tempted at first to abet his cynical employer’s schemes, repents, protects and befriends the heroine, and finally runs Lovelace through the body in a duel. The part is full of fine opportunities, and it is played by Mr. Thorne with a sombre sort of power, for which few of his admirers would hitherto have been disposed to give him credit. Among the other performers Mr. Cyril Maude must be given credit for an admirable bit of character-acting in the part of the miserly old beau Solmes, Mr. Fred Thorne for a roughly spirited performance of Macshane (Tomlinson), while some less prominent, but more or less important parts are skilfully played by Miss E. Banister, Miss Mary Collette, Mr. Blythe, and Mr. Gillmore. A striking item in the scenery is Mr. Hemsley’s elaborate view of Covent Garden Market, after Nebot’s picture in the possession of the Duke of Bedford. Very favourably received at the matinée performance, Clarissa has since taken a place in the evening bill, which it is likely to hold for some time to come.

___

The Athenæum (15 February, 1890 - No. 3251, p.221)

THE WEEK.

VAUDEVILLE.—Afternoon Representation: ‘Clarissa Harlowe,’

a Drama in Four Acts, founded on Richardson’s Novel. By Robert Buchanan.

NOT the least interesting dramas presented before the public are the adaptations of last century novels which are in fashion at the Vaudeville. Occupied necessarily with modern work, the critic finds the time he can devote to re-reading past masterpieces diminish from year to year. Heroic, indeed, or happily dowered with time, would be he who could sit down and read from cover to cover the seven volumes of Richardson’s masterpiece. It is pleasant, then, to see a version of ‘Clarissa Harlowe,’ both for what it presents and what it recalls; for the graces of Clarissa and the persecutions she withstood linger in the background of the memory, and are easily recalled. It is needless to stir the embers of controversy concerning Richardson. Diderot’s famous outburst: “On m’interroge sur ma santé, sur ma fortune, sur mes parents, sur mes amis. O mes amis! Paméla, Clarisse et Grandison sont trois grands drames!” the fact that his works were translated by men such as l’Abbé Prévost, and that ‘Clarissa Harlowe’ was abridged by Jules Janin (as it was in England by Dallas) are unanswerable pleas in his behalf. France, which produced a whole literature imitative of Richardson, was the first country to put ‘Clarissa Harlowe’ on the stage. “Clarisse Harlowe, drame en trois actes, mêlé de chant, par MM. Dumanoir, Clairville, et Guillard,” was produced at the Gymnase Dramatique on the 5th of August, 1846, with Bressant (subsequently of the Comédie Française) as an unsurpassable Lovelace, and Rose Chéri as a delightful Clarissa. This is an old-fashioned work, to which Mr. Buchanan admits his indebtedness. It has saved him some trouble, and though he has departed far from it, the scenes in which he follows it most closely are the most effective. An adaptation of this, with Mr. C. J. Mathews as Lovelace, and Mrs. Stirling as Clarissa, was given at the Princess’s, August 28th, 1846.

Mr. Buchanan’s treatment does not wholly commend itself. One or two characters that he introduces are insincere and out of keeping, and his termination is clumsy and ineffective. None the less he has crowded into four acts very much of a huge plot, and has produced a work that is intellectually and emotionally stimulating. A first act serves for the escape of Clarissa in company with Lovelace from domestic persecution that loses something of its acerbity by the disappearance of Arabella, with whom goes Mrs. Harlowe. Col. Morden, the avenger of the heroine, is also banished, and his functions are assigned to Philip Belford, the correspondent of Lovelace, who is shown as his creature, and, rising in mutiny against his employer, constitutes himself an inefficient protector of the heroine and a thoroughly efficient instrument of vengeance on the hero. Against this there is little to be urged. When, however, in the closing act of apotheosis, Clarissa, endowed with prophetic inspiration, consecrates Belford to God, and he bows his head to receive the chrism, one is scarcely prepared to see him go out instanter to slay a man, however richly the victim may have merited his fate. Clarissa, moreover, in the last act, fine as this is, is too divine and not human enough to create her full effect. There is a suggestion of the teaching of Wilkie Collins in the ‘New Magdalen,’ that the removal of blemish is indispensable to the highest purity. In Clarissa’s case, of course, there is no moral taint. We should prefer her a little less sublimely perfect, and with the humanizing weaknesses Richardson is at the pains to depict.

The characters generally are fairly played. Miss Winifred Emery shows with much sweetness and power the angelical character that Mr. Buchanan has developed, and in her rejection of Lovelace and her communing with Belford touches inspiration. Mr. Thorne, at all events, plays earnestly as Belford, Mr. Cyril Maude is clever as Mr. Solmes, and other characters are creditably presented. Mr. Thalberg is, however, not strong enough for Lovelace; and the character of Hetty Belford, played by Miss Banister, is out of keeping with the play. Mr. F. Thorne gives a clever sketch of character as Capt. Macshane. ‘Clarissa’ was warmly received, and seems likely to take a strong hold of the public.

___

The Illustrated London News (15 February, 1890 - p.6)

THE PLAYHOUSES.

The other afternoon I was talking to a very charming and intelligent young lady, and, young as she was, pretty as she was, and enthusiastic as she might have been, she echoed the same monotonous complaint that we hear so often nowadays: “I want to laugh at the theatre, not to cry!” I had been urging her to go to the Vaudeville Theatre. I had been impressing on her the necessity of studying the “Clarissa” of Mr. Robert Buchanan. I had been dilating with some enthusiasm on the beautiful Clarissa of Miss Winifred Emery, and her death-scene, so infinitely pathetic, so exalted in tone, so illumined by art; but to all my comments she returned the same weary and careworn answer, “I want to laugh at the theatre, not to cry!” Now, had my fair friend been a grandmother and not a girl; had she seen Edmund Kean, and been able to criticise Macready; had she known Helen Faucit in her prime, and carefully differentiated between the methods of a Kate Terry and an Adelaide Neilson; had she in any sense been in a position of being a little bored—why, then one might have excused her. But she had no experience of acting whatever. She had never been astonished into delight by Aimée Desclée or thrilled by Favart or Bernhardt, she did not even allude to the exquisite nature of Miss Terry’s Olivia or Amber Heart, but she stuck to her original position that she loved laughter and hated tears. She went over the stale old ground that life was sad enough without any unnecessary tears at the playhouse. And she candidly owned—highly intelligent and well educated as she is—that the mental recreation that did her the most good was a Gaiety burlesque! Well, do not let us quarrel with the damsel. Each one to his own taste. Still, for all that, I regret, for her sake, the loss of such a mental stimulant, such an intellectual fillip as some win from so beautiful a rendering of a pure and exalted woman as that given us by Miss Winifred Emery in Mr. Buchanan’s new play. I go from the theatre happier from having come across such a woman—for I merge the actress in her personation. This is as it should be. Miss Emery is, no doubt, delightful off the stage as well as on it. Of that I know nothing; not, indeed, do I care to know it. To me she is Clarissa Harlowe, and that is enough for me. I do not want to destroy my illusions; and illusions must, in a measure, be destroyed when actors come away from the footlights.

Perhaps I shall be considered to be saying a very daring thing when I urge that Mr. Robert Buchanan has suffered from producing this particular play at the Vaudeville. It requires just the finish, just the polish, just the sensitive nurturing that it might possibly obtain elsewhere, but which do not belong to the bourgeois style of the Vaudeville. “Clarissa” is a hothouse plant; not a mountain daisy. She would die on Mr. Buchanan’s Scotch moors; she would thrive in an artificial atmosphere. I can see “Clarissa” an immense success at the Lyceum. I can see her even more a success at the Garrick if Mr. Hare had been able to secure both the play and Miss Emery. I can see what Mr. Beerbohm Tree would have done with it at the Haymarket, what a labour of love it would have been to him, and how he would have covered it with an æsthetic halo—just the glow that it required to make it more attractive to the playgoers who shudder at what is sad. Not that by any means the beautiful subject has been neglected at the Vaudeville. Far from it. It is well done, but it wants to be better done. It is very fairly acted, but it requires illuminating power. No one could play Clarissa better than Miss Emery, but there are fine characters in the comedy, and they require to be finely handled. It is no good pouring the finest Chambertin into green hock glasses. It may not destroy the wine, but it destroys the flavour to the cultivated palate. The Vaudeville was not the playhouse for “Clarissa,” nor is the company, as a rule, strong enough to do it the justice it deserves. We keep continually saying to ourselves, “Ah! but if So-and-so had played that part!” This shows that the parts are good ones to play, does it not?

I still think that Mr. Buchanan has made a mistake in reconciling Clarissa with the brutal Lovelace before death releases her; and I also think there was no use in drawing a halo of sanctity round gentle-hearted Philip if he was to go out five minutes afterwards and slaughter Lovelace. Mr. Buchanan very courteously reasons against my objection, and argues that I am wrong. But the intention of the dramatist is on e thing, the effect on the spectator is another. I contend that Mr. Buchanan has so advanced Clarissa on her way to heaven, has so sanctified and purified her, that her reconciliation to Lovelace—even in delirium—is shocking. She is in a state of exaltation. She has had heavenly visions. She has dreamed holy dreams. Her arguments against reconciliation with a repentant man are unanswerable. Why, then, contradict all she has said in delirium, and change from antechambers of heaven to mundane marriages and wedding-bells? That the sin Lovelace has committed is unpardonable on this side of the grave is, to my mind, the great moral of the play. Men may ruin, and are often forgiven by women who love them. But here there was no definite love on the part of Clarissa, and Lovelace betrayed her in the grossest and most unchivalrous manner. That a woman so destroyed is just as pure as a lily trampled under the foot of a clumsy gardener all must allow; but the kiss of a Lovelace to take with her to Paradise is, to my mind, a contamination. The act wants shortening; and the delirium may well be sacrificed. Again, Mr. Buchanan thinks to get over the difficulty of Philip’s revenge by saying that Lovelace “fell upon his sword.” Be this as it may, the effect is that a man who had been vowed to heaven by Clarissa’s prayer is still so earthly that he cannot forego vengeance! The charm that Clarissa has won for her friend by commending him to Heaven would surely teach him the divine knowledge of forgiveness. It strikes me that Mr. Buchanan, by his reconciliation in delirium, and in his accidental slaughter of Lovelace by the sword of a man vowed to God, is unconsciously pandering to the conventionality of happy endings. He knows that the ethical part of his story will not permit the reconciliation of Clarissa with her brutal betrayer, so he unites them in delirium. He knows that the reformed Philip cannot conscientiously be a duellist, so he allows Lovelace to fall upon his sword. But all this is mere special pleading. I maintain that Clarissa, in a beatific state, had no right to kiss Lovelace, and that Philip, converted to the principles of Christianity, should not fight a duel for the purpose of revenge. However, it is a fine play, and is well worth seeing. Miss Winifred Emery has never done anything better in the course of her interesting career. Mr. Thomas Thorne has never been seen to greater advantage than as Philip, one of the most effective characters in the range of modern drama. Mr. Thalberg and Miss Bannister have both physical advantages which should encourage them to go on and prosper. But they both want lessons in voice-production very badly. In a small character Mr. Cyril Maude is excellent; and “Clarissa” deserves encouragement, if the stage is not to be wholly given up to buffoonery.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Winifred Emery as Clarissa Harlowe.]

The Theatre (1 March, 1890)

“CLARISSA.”

New drama, in four Acts, by ROBERT BUCHANAN, founded on Richardson’s world-famous novel.

First produced at the Vaudeville Theatre, Thursday afternoon, Feb. 6th, 1890, and placed in the

evening bill, Saturday, Feb. 8th, 1890.

|

|

|

|

Mr. Buchanan’s version of “Clarissa Harlowe” is not the first by several that have been produced. He admits that he is much indebted to the French dramatisation by M.M. Dumanoir, Guillard, and Clairville, played “at the Gymnase in 1842.” Since then it was seen at the Princess’s in 1846, the adaptors being Messrs. T. H. Lacy and John Courtney, when Charles Matthews (an actor who we all know had not the faintest idea of sentiment or romance) was the Lovelace and Mrs. Stirling, Clarissa. Then there was Mr. Boucicault’s version, and latest Mr. W. G. Wills’s, produced at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham, December 16, 1889. Mr. Buchanan has given us a workmanlike and most interesting play; his language is appropriate, and the introduction of Hetty Belford adds to the strength of the drama. There are blemishes, however. There is something that is almost too horrible in the first act where Lovelace toys with one of his victims (Jenny), and holds out as a reward to her that if she will aid him in his designs, he will get her the situation of waiting maid with Clarissa so that Jenny shall be near him. Again, that men of position like Sir Harry Tourville and Aubrey should pander so openly to Lovelace’s brutal instincts is brought too much in evidence, as is the scene where these men and a couple of infamous women drink success to their patron’s designs on the hapless heroine. Nor does it seem in accordance with the repentance of Belford (the Morden of the novel) that he should immediately after his promise to lead a new life slay Lovelace, who then dies at Clarissa’s feet, she having in a state of ecstatic delirium kissed and forgiven her betrayer as her soul departs. In the last act, too, there is an almost brutal disregard for the feelings of the repentant Hetty, whom by his past conduct he has actually driven to the streets, when in her very presence Lovelace offers marriage to Clarissa as some, though tardy, atonement for the evil he has wrought. Another blemish is the frequency with which the name of the Deity is invoked. Mr. Buchanan has given us an exquisite character in Clarissa, the soul of purity, defiled only in an earthly sense, but a sublime and spotless martyr in Heaven’s sight, and it is for this reason that I should have esteemed his work the more highly had he not so conspicuously brought out the sensuality and animal nature of some of his characters. Though in the first act I thought Miss Winifred Emery a little cold, scarce showing sufficiently the possession that Lovelace had taken of her heart, later she was near perfection; her death scene, though prolonged, was robbed of any sense of weariness to the beholder by its exquisite poetry and beauty. The actress appeared to be almost transfigured, and to be already a denizen of that happier world in which she was so soon to take her place for ever. Mr. Thalberg, though very good for so young an actor, was neither romantic nor passionate. Such a character as Lovelace, a man who can obtain such conquest over women of every grade, should be thoroughly captivating towards them; when he tires of his playthings of an hour he might be heartless but he should not be cynical. Miss Banister surprised me by her power as Hetty. Her elocution was very faulty and her bursts of emotion were undisciplined, but there was distinct evidence of a capability, that study and experience will develop into the accomplishment of great things. Mr. Thomas Thorne was earnest and sincere as Belford, a man who has lost faith in woman since his sister’s disgrace, but whose heart is moved at the innocence of Clarissa. His scene with Lovelace when taxing him with his treachery, and his endeavour to rescue the profligate’s fresh victim, was intense and vivid. Mr. Cyril Maude was excellent as Solmes, the old lover, intended by her father for Clarissa’s husband. Mr. Fred Thorne, Miss Mary Collette, and Miss Lily Hanbury also deserve very favourable mention. Mr. Hemsley has in the second act given us a capital reproduction of Covent Garden Market as it appeared in 1749, and the dresses by Nathan & Co., from designs by Karl, are handsome and correct. “Clarissa” was so well received tbat it was placed in the evening bill almost immediately.

___

The Academy (1 March, 1890 - No. 930, p.158-159)

THE STAGE.

“CLARISSA” AT THE VAUDEVILLE.

THE new “Clarissa” has distinct merits. It is interesting. I am glad to have seen it. But I cannot, in holding forth on piece or performance, emulate the hysterics of a certain daily newspaper. At the same time, one ortwo of the charges that have been brought against it by the less continuously gushing appear to me little deserved. The production is creditable to everybody who is concerned in it. But I doubt if, six months hence, we shall be found reckoning it among the triumphs of the Vaudeville management.

As regards Mr. Buchanan’s part in the affair, it has, it seems to me, been one of greater difficulty than when it was his business to dramatise Tom Jones and Joseph Andrews. The interest of Tom Jones is, half of it, in action; the interest of Joseph Andrews is, half of it, in adventure. But the interest of Clarissa is psychological, and Mr. Buchanan’s play is not psychology. He is prevented, by the conditions of the theatre, from showing us the infinite and almost imperceptible stages by which the heroine is led to that which, in common parlance, is described politely as her “ruin.” Will she be seduced? Or will she never be seduced? Will Clarissa yield? Or will Clarissa elude the pursuer, charm he never so wisely? We ask these questions through page after page of the romance—through sheet after sheet of that voluminous correspondence which the brain of Richardson imagined. At the theatre, this matter must be settled more promptly. And the elaborate analysis of motive and feeling which the eighteenth-century novelist permitted himself has perforce to be abandoned for a drama faithful enough, as Mr. Buchanan claims, to the main incidents—even to the main spirit; but from which, inevitably perhaps, something which was the source of the novel’s interest has, to a great extent, gone.

But though many thoughtful readers must feel this to be the case, the dramatist may reasonably get credit for the judgment and dexterity with which—the conditions of stage representation being what they are—he has handled the theme. And, so far from blaming him for the very prominent introduction of Philip Belford and of his sister Hetty—who, as M. Zola and other novelists of l’hérédité will be glad to note, go to the devil each in his own way—we ought, I think, to see at once that Mr. Buchanan was right in conjecturing that the contest between Clarissa’s chastity and Lovelace’s persistence could not alone occupy the stage—that there was need of some other interest. And he has introduced this new interest with a great deal of skill. Philip Belford and Hetty are, to my mind, thoroughly sympathetic ne’er-do-wells. Philip, it is true, stooped low; but he stooped with genuine regret. Even in his cups, he is inoffensive. And you cannot be very hard on Hetty, wild and kind-hearted—nay, devoted at need. Without these characters, the play would have lacked much of value that it now possesses. Mr. Buchanan, when he chooses, can invent so well, is it not almost a pity that he should continue chiefly to adapt? To finish with his part in the present production, let it be said that the language of the drama is vigorous and direct; and, as a whole, sufficiently, without being obtrusively, old-fashioned. Here and there, there are lapses. I may, of course, be wrong; but, from the lips of Lovelace, the phrase “a coup de théâtre” sounds a little modern.

In the dramatisation of what is not only intellectually a very great, but as regards mere bulk also, an immense novel, there are likely to figure a far larger number of characters than if it had been left to the dramatist to invent his own fable. And, as the drama proceeds, several of these characters are wont to be dropped upon the way. In “Clarissa,” after the first act, we see nothing more of three people not unimportant “in their day”—Clarissa’s father, Clarissa’s brother, and a wealthy neighbour, Mr. Solmes, who is a pertinacious suitor for Clarissa’s hand. Mr. Solmes, the most important and designedly the most entertaining of the three, is so well played by Mr. Cyril Maude that we are sorry to lose him. As a suitor, Mr. Solmes has nothing to recommend him but self-confident piety and a great estate; but as a person of the drama, the pungency and quaintness of Mr. Cyril Maude make him unquestionably welcome. Lovelace is enacted by Mr. Thalberg—who is good, but not quite good. I mean that while his natural gifts, and a long and successful experience—as I hear—in the provinces, have removed him entirely from the ranks of the incapable—have made him to some extent an accomplished actor—he yet is hardly the ideal Lovelace. The ideal Lovelace would be even more fascinating, even more persuasive, even more forcible, and at need more violent. Mr. Blythe is amusing as a farm-bailiff, very accessible to argument when argument takes the form of cash; and—to name a tiny character part—the part of the watchman, in his momentary appearance, is well played and looked by Mr. Wheatman. But no character in the piece is more thoroughly filled out to the utmost of its narrow possibilities than is that of young Aubrey—a friend of Lovelace’s—looked and played by Mr. Frank Gillmore with admirable lightness and elegance. Next to Lovelace— whom I have already discussed—the two most important men’s parts are those played by the brothers Thorne. Mr. Thomas Thorne exhibits very skilfully and sympathetically the humours and the regrets of Philip Belford—the unwillingness with which a man whose moral force, whose power of resistance, is for the time gone joins in the plot against Clarissa; and, again, the tenderness and courage with which, at need—summoning back again the best that is in him—he prepares to defend her. The part offers to Mr. Thorne a large measure of variety; and the actor avoids monotony, and is earnest and convincing. A variety necessarily more obvious is attained by Mr. Fred Thorne, in a part that is wholly of comedy. Captain Macshane, a soldier from beyond the Border, assumes the garb of a divine in order that he may do Lovelace the service of performing a mock marriage. And, at the wedding feast, he lifts up his voice in a song which strikes Clarissa as not exactly suited to the ecclesiastical character. The low or the eccentric comedy of Mr. Fred Thorne is always acceptable; but he is seen to greatest advantage in a part that makes some demand upon feeling likewise.

Mr. Buchanan’s “Clarissa” is anything in the world but a one-part piece; and Miss Winifred Emery, as the heroine, may be justified, perhaps, in being judicious and tender, rather than actually great. Her very visible intelligence, her real delicacy of perception, and some physical gifts which are as apparent, will carry her far; and her performance already is admirable, though it is not perfect. In what ought to be the great scene of the third act, I wanted her to be bigger. Here the climax of emotion was surely reached, but somehow I was not aware of it. That Miss Emery looks the character need hardly be said; and, as one would expect from her, she executes her conception generally with subtle touches. Nothing, for example, could be better than her first indications of definite suspicion when Clarissa is in reality in Lovelace’s house, while it pretends to be that of his imaginary kinswoman. And earlier than that—in the first act— Clarissa’s hesitation is well expressed by her. Very “maidenly”—if one must give her behaviour its usual phrase—is her behaviour to Lovelace. In the fourth act, Miss Emery is to be greatly commended for sparing us the worst of what Bacon speaks of as “the dolours of death.” For Clarissa, indeed, the sweetest canticle is “nunc dimittis.” And Miss Emery understands that there must be pathos rather than terror. Of the other ladies who are engaged in the piece, let it be mentioned that Miss Mary Collette is satisfactory in the small part of a young country woman; that Miss Hanbury—who is almost a débutante—acts a good-hearted, impulsive, Covent Garden market girl with naturalness, freshness, and happy assurance; and that in the really considerable character of Hetty Belford, Miss Banister is forcible as well as picturesque. Of scenic effect there is throughout the piece enough and not too much. The market scene is very prettily suggested, but the necessary business of the play never waits by reason of a superfluity of “supers.”

FREDERICK WEDMORE.

___

Pall Mall Gazette (4 March, 1890 - p.1)

AFTER “CLARISSA,” “THE RELAPSE.”

The version of Sir John Vanbrugh’s comedy “The Relapse,” which is being prepared by Robert Buchanan for the Vaudeville, will see the light—at a matinée of course—as soon as it is ready. If successful, you may expect to see it oust “Clarissa” from her place in the evening bills, as this drama has not done all that the management anticipated. I should have liked to see so sound and artistic a play—for with all its faults it never lacks true art—become a really popular “triumph.” But the average theatre-goer is a strange creature. You may make him laugh in almost any way you please; but he is very particular as to the precise method in which you extract tears from his critical eyes. Presumably, he does not find sufficient enjoyment in weeping over the woes of the unfortunate Miss Harlowe.

___

Time (April, 1890 - pp.435-439)

An adaptation, a poem, and a note. Not content with giving us a four-act play cleverly built out of perhaps the most undramatic novel ever written, Mr. Buchanan gives us a little poem of his own among the dentifrice advertisements, and a note explaining that for the one dramatic fourth of the play he is indebted to the Gymnase drama of Dumanoir, Guillard, and Clairville. Undramatic as the subject is, and undramatic as much of the treatment almost of necessity must be, yet it is undeniable that “Clarissa” holds the attention of the same shop-keeping class that sees no pathos in Nora. Winifred Emery’s acting is really wonderful. It is questionable if anything short of actual genius could keep together that hour upon hour of dying in the fourth act. And yet the act and the piece are kept together by the work, almost unaided, of this young actress. Mr. Thalberg helps in the earlier acts, and if he had not quite such a fine figure and quite such good teeth he would be much more useful. Mr. Thomas Thorne is too old and clever a stager to make any mistake, and his Belford is a sterling, thorough piece of work whenever no pathos is required. Only two points of general criticism. Would not the end of the third act be better with “Clarissa” fainting on the sofa as she is a moment before that end, instead of the present finish? The latter is on this wise. Lovelace performs the excellent gymnastic feat of carrying “Clarissa” across the stage and half-way up the stairs to his bedroom, and then “imprints on her lips” an anything but chaste salute. We prefer the simpler ending. Not from any notions of prudery, but from the point of view of dramatic significance. And the ending of the play would be better, as we think, without so much rather ostentatious blessing on the part of “Clarissa,” because she has had a little trouble with Lovelace, and surely better if she did not embrace him lover-fashion at the finish. Either she is a weak girl, loves him still, and will yield to his offer of marriage, or she is a strong woman, loathes him for the wrong done to her, and to all womanhood, and then she would not kiss and embrace him, but go on blessing him as she has blessed all the rest.

The first-piece improvement mania – a very amiable form – has even infected the Vaudeville, that most conservative of theatres. “Meadow sweet” is necessarily as slight as a maiden of fifteen must be. But it is graceful and full of character as well, and it is very cleverly played by “all concerned,” with one exception. Miss Ella Banister is not the fresh and rose- milk country maiden of the author and the piece. She is not quite able to throw off the town airs she catches nightly outside the Bell Tavern in Covent Garden in the second act of “Clarissa.” All the others are admirable, and Cyril Maude’s living, not acting, of a country cad, turned town snob, is a piece of condensed genius. We have used that word twice already in this notice in respect to a husband and wife. For Winifred Emery is, as all the world knows, Mrs. Maude. In their art they are also one.

Alec Nelson [pseudonym of Edward Aveling]

[This review appears on the Marxist Internet Archive in the Eleanor Marx Dramatic Notes section.]

___

The Theatre (1 April, 1890)

[From ‘Our Omnibus-Box’.]

PUBLIUS TERENTIUS AFER, ESQ.

20th March, 1890.

MY DEAR TERENCE,—

A young person I know told me the other day that Henry I. of England died of a surfeit of palfreys. This set me thinking (why?) of the villa near Puteoli, facing the blue Tyrrhene sea, where the secret of thy literary co-partnership with Lælius and the young Scipio formed many a jesting theme for conversation, maybe, over twinkling bumpers of Setian wine, heady enough to wash the throat clean through those long, strong revels of gluttony that hailed the fat Ambracian kid, and dropsical apple-snail, and perhaps the rich lamprey from distant Britain as rare bon-bouches. How we can picture the flushed cheeks and the fair chaplets of roses reeling over drunken brows, as the balmy wind steals in by way of fluted pillar and tessellated pavement, and cools its bosom against the tinkling fountain in the peristyle, and venturing further, flies again, let us hope, from the hot, lascivious atmosphere of the triclinium, to sob itself pure in the arms of Naples Bay. For the air of Puteoli villa was not good for the least of Nature’s chameleons, and the quips and quiddities that went round at its orgies would have proved strong meat, perhaps, even for a Lovelace. Ah, me! the merciless luxuries—which podgy Gibbon preferred to call refinements—of those ancient days! the heathen indulgence and brutal pursuit! the prurient beast in his exotic palace, and the helpless Miriam writhing, in her shame, or poor Nest from her northern eyrie standing with the blue of the sea in her eyes and death in her heart! I can have no sympathy with you here, Terence—now less than ever, for I have lately been to see “Clarissa” at our own little “Vaudeville,” and the cleansing fever of repentance is burning in me still. Lovelace! he was a Bayard to you all. If you would have chuckled richly over his fiendish intriguing, you would have sneered proportionately at his remorse; no dew of pity ever nourished green germs in your breasts. The tears of wretchedness fell thereon like rain on asphalt, finding no interstices to woo a single wandering seed. I can fancy sweet Clarissa done to moral death, in thy outrageous Rome, and no poignard for her betrayer’s bosom, and, worse, no angel’s comfort kissing her to her own young decline. Is not thine unhappy ghost, “blown along a wandering wind,” hounded ever on now remorselessly by the harpy presentments of such piteous, yellow-haired slaves from over the water as thou and thy kind so often and so cruelly wronged? I hear, methinks, a shadowy chuckle in the hollow of the sky! “Not from thy hand, libertine, this stone to our memories!” Alas! who am I to cast blame! Did not I once woo Billy Waghorn’s sister from the arms of Joe Pringle with lure of “brandysnaps” cunningly warmed in the breeches pocket to the consistency of toffee? I mind me also of Mary Earwaker, of the New Cut, formed for man to “waste his whole heart in one kiss upon her perfect lips,” but whom, nevertheless, I abandoned for that she developed a plebeian stye in one of her gem-like orbs. These things do not bear dwelling upon in the ecstasy of my late bitter reformation. For I have seen “Clarissa,” and am humbled. And who is Clarissa? you will ask. Ah! that I can tell you. She is Winifred Emery and no other, and Winifred Emery is Clarissa. Surely all is said here. But whose the play? say you, the cunning adaptor of old. Ah, Terence! she belongs to no play, but to fact. And yet was her piteous ladyship introduced to the too-little-thinking life of to-day by one who can run even you close in your peculiar line, my “dimidiate Menander.” Buchanan the playright is not uniformly true to his finer instincts; the author of “White Rose and Red” is not always to be depended upon for such a little thing as grammar; but Buchanan the adaptor has no equal in extracting the germ of beauty and truth from a bog of verbiage and prolixity. Prurience! I tell you never was play of pimps and harlots more pronounced and less indelicate. As old Richardson set his heroine in extenso, so has his latter-day interpreter in nuce—a jewel in a dunghill. A diamond never glitters as it does on black velvet; the darker the evil horrors surrounding, but never overwhelming, the outraged girl, the fairer her soul shines forth in contrast. It is a picture that most may weep over and all appreciate. We may find our eyes wet as the curtain falls, without shame; we may acknowledge the influence wrought in our natures and justify it in our after lives with no loss of manliness. Call it a play if you will; I, for one, shall always think of Winifred Emery as Clarissa, and whatever parts she may essay hereafter—and the Gods grant they may be many—the image of that dying heroine will colour and sanctify them all.

Yours distantly,

(Particularly so at present),

THE CALL-BOY.

___

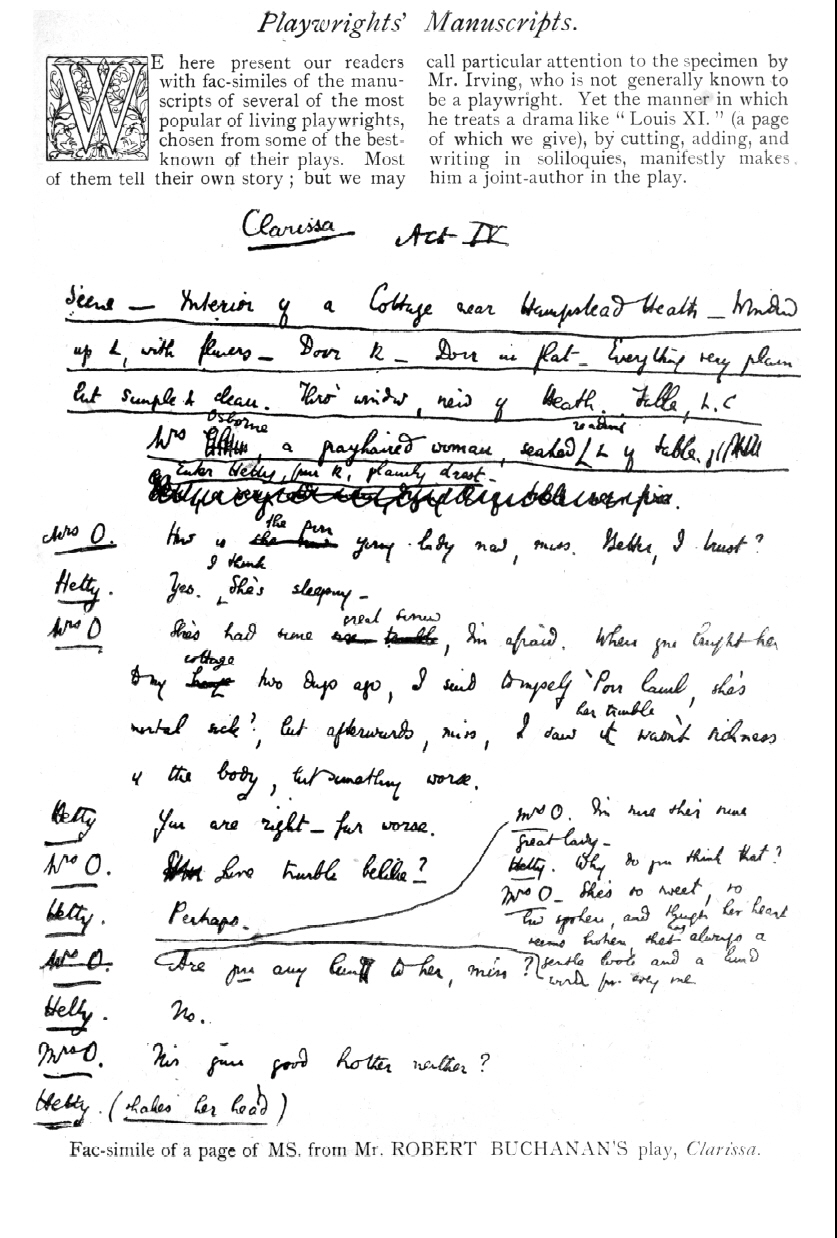

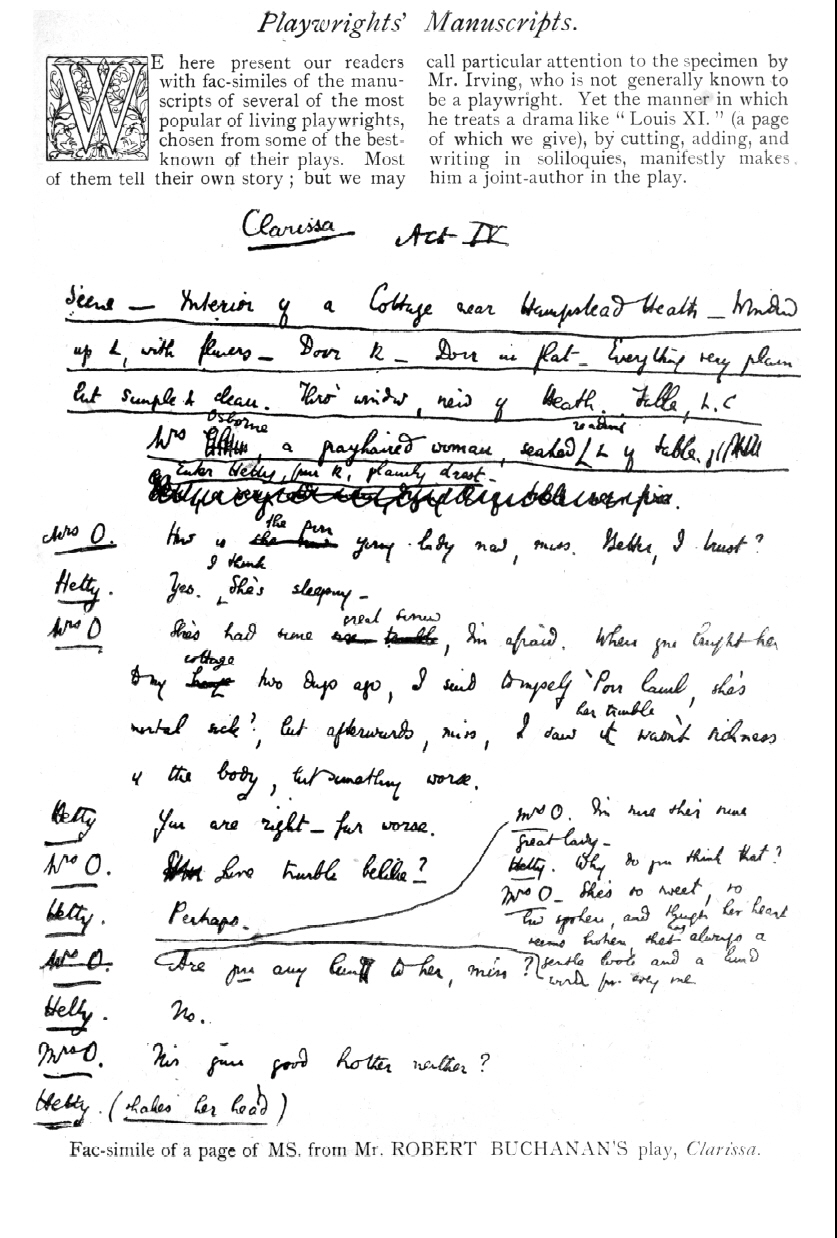

The Strand Magazine (April, 1891 - p. 415)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From Playhouse Impressions by Arthur Bingham Walkley (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1892 - p 157-162):

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

“CLARISSA.”

(Vaudeville Theatre, February, 1890.)

AT the first performance of one of Voltaire’s tragedies, freely purloined from a Greek original, it is said that the author leant out of his box and shouted at the somnolent pit, “Applaud, you idiots; that’s Sophocles, not Voltaire!” At the Vaudeville I hid behind a fair neighbour’s monumental hat, in mortal terror lest the author, leaning out of his box, and catching me falling asleep in the wrong place, should shout, “Don’t yawn, you idiot; that’s Richardson, not Buchanan!” Which is which? The harassing question recurred with each fresh entry, each successive incident. Is it Buchanan, and may I yawn publicly? Or is it Richardson, and must I dodge behind my neighbour’s hat? Into such an abyss of doubt is one cast by respect for a British classic whom one has neglected to read. Neglected is hardly the word; it should be, refused. Despite the injunctions of my pastors and masters; despite the temptation of getting the whole set of eight volumes from a second-hand bookstall for fourpence, I have always refused to read “Clarissa Harlowe.” If any one asks why, let him be answered by this scrap of dialogue reported by Boswell:

“ERSKINE: Surely, sir, Richardson is very tedious?

JOHNSON: Why, sir, if you were to read Richardson for the story, your impatience would be so much fretted that you would hang yourself.”

Perhaps some rude person, who fails to perceive the true inwardness of Impressionist criticism, will say that he doesn’t care a straw whether I have read the book or not, that that is my affair, not his. Let such an objector just consider what would have happened if I had read Richardson’s book without going to see Buchanan’s play. Obviously my judgment would have been cut-and-dried in advance. It would, according to time-honoured practice in such cases, have been a string of lamentations over the shocking fashion in which the audacious modern had mangled the venerable ancient. The word sacrilege would have appeared at least a dozen times in my notice, and there would have been dark allusions to body-snatchers, resurrection men, ghouls and other such fearsome things. Now, my ignorance of the book has saved me from all this.

Moreover, it enabled me at the Vaudeville to enjoy that pleasant sport known to the French code as la récherche de la paternité. Where did Richardson come in? Where Buchanan? And where Dumanoir, Guillard, and Clairville? But who, you ask, are Dumanoir, Guillard, and Clairville? Mr. Buchanan himself answers this question in a note on the programme. They were the joint authors of a French dramatisation of Richardson’s novel, made famous by the acting of Bressant and Rose Chéri. Mr. Buchanan (or more probably the programme compiler—an accurate programme the eye of man hath not seen) says this play was produced at the Gymnase in 1842. The correct date is August, 1846. Jules Janin and Théophile Gautier went into ecstasies over this piece; and when a French dramatic critic of 1846 became ecstatic the air was thick with meteoric adjectives, I can tell you. But it is perhaps time that my own adjectives began to coruscate. Let them flash first upon Mr. Thomas Thorne. The first guess I hazard is that there is mighty little Richardson in this gentleman’s part. One may get at that à priori. A leading character, obviously, must be found for the manager, and the only leading characters in this novel (one may be permitted to know so much without having read the book) are Lovelace and Clarissa. Now, the wildest imagination refuses to conceive Mr. Thomas Thorne as Lovelace, and it is equally difficult to suppose him playing Clarissa. Hence I take the part of Philip Belford to be the joint invention of the English and French dramatists. Belford is a drunken ne’erdoweel, turned misogynist by the death of his wife and the ruin of his only sister, Hetty. Through the man’s sottishness glimpses of a better nature are perceived. Hardly has he helped Lovelace in the plot against Clarissa when he repents, and, finding that it is Lovelace who is his sister’s betrayer, resolves to save the woman and kill the man. In the first enterprise he fails, for the same drugged wine which makes Clarissa Lovelace’s helpless victim disables Philip Belford just as he is on the point of effecting her rescue. But it is Belford’s sword by which Clarissa is avenged. The actor overelaborates the part in his own well-known fashion, though apparently to the complete satisfaction of those play-goers who like their pathos sung—and sung adagio—and sung on one note. His quaint humour, which made the fortune of his Partridge and his Parson Adams, here gets no scope. We shall probably be safe in assuming that what Belfonl is belongs to Mr. Buchanan, what he does to our friends Dumanoir, Guillard, and Clairville. Hetty Belford, Philip’s fallen sister, is, one supposes, Buchanan du plus pur: she has that melodramatic air which betrays late nineteenth-century work. One may risk the same guess about Captain Macshane, a Sir Pandarus of Troy, with a broad Scotch accent, who masquerades as a clergyman and makes a happily frustrated attempt to sing “The Gowden Vanitee.” It is a droll part, and is “composed” with care by Mr. Fred Thorne. Clarissa’s heavy and unrelenting father becomes a terrible personage in the hands of Mr. Harbury. Fortunately he disappears after the first act. So—not so fortunately—does Mr. Solmes, Clarissa’s rich elderly suitor, a character very cleverly sketched by Mr. Cyril Maude. Miss Mary Collette plays a little rustic coquette prettily, and Messrs. F. Grove and Frank Gillmore both give the conventional stage picture of an eighteenth-century man of fashion, i.e., satin clothes, many flourishes of the hat, frequent “Fore Gads,” and a strut.

Coming to the Lovelace, I find myself in a quandary. You see, my ignorance of Richardson’s book prevents me from knowing what sort of a Lovelace Richardson’s Lovelace was. Mr. Thalberg may be that man. If he be, why, so much the worse for Lovelace and Richardson and Mr. Thalberg. Whatever may be the case with the printed page (especially in Richardson’s epistolary form where there is room for the slow development of a psychological study) one cannot stand a character of this sort, a creature of unqualified moral turpitude, on the stage of to-day (outside sheer melodrama) unless one gets an intellectual impression. I cannot be interested in a mere well-dressed rake. No doubt the Don Juans of real life are often poor, empty creatures. Women have a strange taste. But if you bring Don Juan on the stage, you must make him a Don Juan that satisfies my imagination. There must be a magnificence about the fellow; he must be a virtuoso in the Fine Art of Don Juanism; must have maestria; must be a philosopher like the Don Juan of Molière; a heroic figure that will not make Leporello’s catalogue sound ridiculous; a host not too puny to invite the statue of the commander to supper. How else will you satisfy a generation that (if it does not read “Clarissa Harlowe”) is very familiar with Feuillet’s M. de Camors and Daudet’s Due de Mora? I recognize the dramatist’s difficulty here. A character of this complexity is not easily rendered by the simple methods of the stage. It is something like the difficulty Lamb complained of in the representation of Shakespeare’s colossal villains. They lose their intellectual charm before the footlights, where, e.g., “the profound, the witty, the accomplished Richard” is apt to become a mere ogre. Now, this Lovelace is no virtuoso in Don Juanism. He is no seducer, even. He is a vulgar cheat, who flourishes his handkerchief, takes snuff with an air, uses foul drugs, and—one must put a brutal fact brutally—commits a rape upon his victim. Don’t ask me to be interested in this fellow. He is a poor, cheap, sawdust-stuffed creature, an eighteenth-century vibrion. And when Belford kills this vibrion, as Clarkson in Dumas’ play kills the other, the vibrion’s return to gasp out his dying repentance over his dead victim’s body only fills me with disgust. A Don Juan who cannot “see it through”—bah! All this is not to say that Mr. Thalberg fails to do his best with the part provided for him. But if that part be Richardson’s Lovelace I shall never regret my ignorance of Richardson. Of Miss Winifred Emery’s Clarissa one can only say that it is, in Mr. Ruskin’s pet phrase, “an entirely beautiful” performance. The reading of the poor artless little will in the final scene is tear-compelling. And, while you weep, you enjoy the pleasure of harmless speculation into the bargain. Is this a true Richardson tear? you wonder, as it trickles down your nose. Or is it a Buchanan drop? What if it should be only a spurious French tear, a tear of collaboration, the tear of Dumanoir, Guillard, and Clairville? Here are diverting questions, the answers to which Miss Blanche Amory may write down in that little volume of hers, entitled “Mes Larmes.”

|

|

|

|

|

|