|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 21. Partners (1888)

Partners

The People (25 September, 1887 - p.4) HAYMARKET. In face of an audience at once distinguished and friendly, Mr. Beerbohm Tree, the youngest of enterprising managers, inaugurated his management of the Haymarket on the 15th inst. with an entertainment as craftily qualified as Cassio’s second cup, consisting, as it did, of “The Red Lamp,” a drama which had successfully found its feet and gone off with a run at the Comedy; and also, by way of imparting the piquancy of novelty to the programme, a new romantic one-act play entitled “The Ballad Monger,” adapted by Messrs. Besant and Pollock from a favourite French piece entitled “Gringoire.” . . . Between the pieces Mr. Tree, after a few brief words with reference to the excellent accommodation in the boxes, afforded as “an honourable compromise” to the pittites, took the audience generally into his managerial confidence by informing them that “The Red Lamp” would be followed by a piece by Mr. Robert Buchanan, an arrangement, by the way, which had already leaked out, and that the next novelty in succession would be an historical drama by Mr. W. G. Wills and Mr. Grundy. This announcement was welcomed with a hearty burst of applause, the more significant as contrasted against the dead silence ensuing upon the reference to Mr. Buchanan’s piece and also the promised re-appearance at a later date of Lady Monckton. ___

The Era (15 October, 1887) MR BUCHANAN’S new comedy-drama is in active rehearsal at the Haymarket. It is in four acts, and will be entitled The Senior Partner. The cast will include Miss Marion Terry, Miss Achurch, Miss Le Thiere, Mr Brookfield, Mr Kemble, Mr Lawrence Cautley, and Mr and Mrs Beerbohm-Tree. The statement which has been circulated, to the effect that this play is a mere adaptation of a French novel, is without foundation. Though several suggestions have been taken from a foreign source, the work is in the main original. ___

The Era (22 October, 1887 - p.7) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN has given up the title of The Senior Partner for his new piece at the Haymarket, and has decided to call it The Honour of the House. ___

The Graphic (22 October, 1887 - p.13) The next production at the HAYMARKET will be a new play, by Mr. Robert Buchanan, entitled The Honour of the House. It will find employment for the whole of Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s company, including Miss Janet Achurch and Miss Le Thière, who have lately been engaged. It may be well to note that Mr. Buchanan’s piece is not an adaptation of L’Honneur de la Maison, though it owes something to a French novel—M. Daudet’s Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé, ___

The New York Times (8 December, 1887) The new piece written by Robert Buchanan for the Haymarket will be called “Partners.” The play, which was to have been produced on Saturday, will not be brought out until Jan. 5. In addition to the regular company of the Haymarket the services of Misses le Thiere and Kingston have been secured. The latter lady is a well-known professional beauty who has had some experience in the provinces. She will be intrusted with an important rôle. The story of the play is as follows: An old German merchant is possessed of a beautiful wife, with whom his partner falls desperately in love. The German trusts both man and woman implicitly, despite the warnings of friends and enemies. During her husband’s absence on the Continent the wife has a passionate love scene with the partner, in which she confesses her love. He urges her to flee with him, which she is about to do, when the voice of her child is heard calling her from an adjoining room. This brings her back to her proper self, and she refuses to betray her husband. This is an excellent scene, and although the idea has been used before Buchanan’s treatment of it is forcible. The husband returns after being ruined by the failure of a Continental firm. From a conservatory he sees the two together and hears the woman avow her love for Charles, but he does not hear her avow that gratitude and respect preclude her from wronging her husband, even if the motherly love stirred by the voice of her child was not sufficient. Further, he is poor now, and her duty compels her to remain. The husband’s eyes are at last opened, and in a strong scene he drives her from his house without listening to her story. In the fifth act it is Christmas, with its sacred and peaceful associations. The old man’s heart, touched by the gladness around him, breathes forgiveness on his wife and partner, and the curtain falls on a holly-decked apartment in which once more reign domestic peace, happiness, and love. |

|

|

[Advert for Partners from The Stage (6 January, 1888 - p.11).]

The Times (6 January, 1888 - p.9) HAYMARKET THEATRE. In a note appended to the bill of his new play of Partners, which was produced at the Haymarket Theatre last night, Mr. Robert Buchanan intimates that the principal character, Heinrich Borgfeldt, is “founded upon that of Risler in M. Alphonse Daudet’s novel of ‘Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé,’ but that, while numerous suggestions have been taken from the book, the leading situations and most of the dramatis personæ are radically different.” It would be easy to join issue with Mr. Robert Buchanan upon the question of his alleged independence of M. Daudet’s novel, but this would be a needless as well as an ungracious task. We quote his acknowledgment of the source of his inspiration in connexion with Partners not for the purpose of proving, what is already well known, that an adapter is apt to develop something of a foster-mother’s fondness for the little foundling under his charge, but because it explains certain of the imperfections of the piece, which the first-night public noted with their accustomed frankness. “Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé” is unsuited to dramatization. M. Daudet himself has attempted the task and failed. Mr. Robert Buchanan has no doubt been wise, therefore, in endeavouring to shake himself free of the trammels of the novel; but the charm of that intensely realistic book has evidently pursued him throughout his undertaking to the extent of crippling the imaginativeness and the apt observation of character of which on other occasions he has given abundant proof. Regarded as an adaptation, Partners is a work of skill; the only question it raises is whether Mr. Robert Buchanan has not unduly handicapped himself in transplanting to London a story and a set of characters essentially Parisian in their growth, and governed by a code of morals which the Lord Chamberlain has not yet seen his way to accept. ___

The Morning Post (6 January, 1888 - p.5) HAYMARKET THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play, entitled “Partners,” was produced last night at the Haymarket Theatre with the most gratifying tokens of success. The story, which the author frankly acknowledges was suggested by Daudet’s novel, “Froment Jeune et Risler Ainé” is of pleasant simplicity. It concerns the ruin brought on a mercantile firm and the destruction of the domestic happiness of the senior partner by the expenditure and lax morality of the junior partner, the restoration of credit and the cementing of the household gods being brought about by the self-sacrifice and nobility of the elder man in a way not unfamiliar to the stage. Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s impersonation of this character is perhaps as fine a thing as he has ever done. Nothing could be more winning than his tenderness in the lighter phases, and little within the limits of true art more powerful than his portrayal of grief and agony in the darker moods of the part. At the termination of the third and fourth acts he was called again and again to receive the acclamations of the house. Perhaps the most striking character after that of the hero is the one played by Mr. Brookfield, who, wonderfully made-up, impersonates a retired actor with rare humour and effect. Miss Marion Terry gives a sympathetic and touching rendering of the sorely- tempted heroine. Miss Le Thière has a pleasant part, which she fills with geniality and aplomb. Miss Gertrude Kingston is appropriately gay and vindictive by turns as a wicked woman of the world. Miss Achurch is supplied (not too well) with opportunities for the display of her skill, and Miss Minnie Terry is one of the most delightful of stage children possible. Mr. Laurence Cautley plays the villain with ease and finish, and Mr. H. Kemble is admirable as an old clerk of the imperilled firm. The play will need some compression and curtailment, and then with such acting as it contains its lasting success seems assured. ___

The Echo (6 January, 1888 - p.1) THE THEATRICAL WORLD HAYMARKET THEATRE. Whatever may be said of the new comedy drama Partners, with which Mr. Buchanan presented the public last night at the Haymarket Theatre, it can hardly be urged that it is a wholesome play. The story, though much involved, is in reality a short and simple one. It is that of a rich German merchant living in London named Borgfeldt (Mr. Beerbohm Tree), who has married—by means of money lent to her father—a young and beautiful lady, of somewhat flighty ideas, named Claire (Miss Marion Terry). He has a young partner called Charles Derwentwater—a married man, by the way—who is desperately in love with Borgfeldt’s wife, and is besides a sort of “conventional lady-killer,” whom married women generally are supposed to admire. Derwentwater ruins the firm by his extravagance, and takes advantage of the absence of his old partner—who has rushed off to Germany in order to save, if possible, the credit of his house—to attempt the ruin of Mrs. Borgfeldt also. Here sympathy can hardly be said to rest with anyone. The old German has married the girl by means of money, one can hardly weep over him; the girl herself, though petted by her old “bear of a husband,” is too openly deceptive to deserve any sympathy; the youthful partner is certainly a very stagey lover, and attracts very little interest. The only actor in the play at this time that draws pleased attention from the audience is Miss Minnie Terry, who, as the little daughter of Mrs. Borgfeldt, rushes into the room at the critical moment when her mother’s honour hangs in the balance, and presumably saves her. Presumably only, however, for the husband, returning suddenly, certainly catches Mrs. Borgfeldt in a most compromising situation, and turns her out of house and home. Still, for some inconceivable reason, while he discards his wife he retains his partner; the firm is nearly ruined, but he intends to work as a clerk, and so save the good name of the house. The partner continues with him, and at the close, on a Christmas-day, when Borgfeldt becomes reconciled to his wife, the health of Derwentwater is actually drunk in a bowl of punch. Such is roughly the story of The Partners. Of course, there are a lot of side issues in the five acts, which are successively called “Mrs. Borgfeldt at Home,” “The Junior Partner,” “The Honour of the House,” “The Senior Partner,” “The Christmas Carol”; but they do not greatly affect the spectator, though they introduce a number of actors and actresses upon the stage. ___

The Standard (6 January, 1888 - p.3) HAYMARKET THEATRE. The successful Red Lamp was last night replaced at the Haymarket by a five-act play called Partners, written by Mr. Robert Buchanan. The author acknowledges some indebtedness to the well-known novel “Froment jeune et Riola ainé,” but he claims the credit of inventing many of the incidents of the drama, and this credit must be given him, though in truth most of the personages have recognisable prototypes in fiction. Partners, as will be judged from the reference to M. Daudet’s book, is the story of an elderly man, whose trust is placed equally in his young wife and in his friend and partner, and who is driven to believe, with much reason, that they are both false to him. The scheme furnishes opportunity for some remarkably powerful and affecting scenes, but a fault of the play—apart form its extreme length, which is the more inexcusable, because there is not a little repetition in it—is its persistent atmosphere of mournfulness. More than once or twice during the evening it was felt that the acting saved the play, and that but for the personal interest which some of the characters evoked, the depressing influence of the story would have brought about its condemnation. When it has been considerably shortened, it will be materially improved, and it will then remain to be seen whether, in the opinion of audiences, its power atones for its painfulness. Borgfeldt, the senior partner, in an apparently wealthy firm, is, as he supposes, happy in the possession of a charming wife, a bright little child, and a partner, Derwentwater, who, except for some indifference in the matter of business, which signifies little, is all that a partner should be. Borgfeldt knows his own shortcomings. He is clumsy, unused to society, feels strange in his handsome house, for he is unaccustomed to luxury; and, indeed, is made absolutely uncomfortable by the stateliness of his butler, whom he deferentially addresses as “Mr. Dickinson”; and here, it should be said, that it is mainly to Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s remarkably courageous and skilful handling of this character that such success as the play may gain, will be due. It seems impossible when “the old bear,” as he calls himself, first appears, with his odd constrained manner, strongly marked accent, and ungainly appearance—ill-fitting clothes, intractable hair, and general uncouthness—that he can win the sympathy, regard, and respect of the audience as he speedily does. Borgfeldt, however, is suddenly called away, almost at a minute’s notice, to Germany, and this at a time when the attachment between his wife Claire and Charles Derwentwater is passing the limits of flirtation. Her evil Genius, who, for motives of personal revenge, tempts her to her ruin is a certain Mrs. Harkaway. A passionate scene between the lovers, as they must be called, takes place one night after a return from the theatre, and Claire has ceased to repulse her husband’s friend, when her child, who has been waiting for her mother’s good-night kiss, runs into the room. To many spectators the introduction of the child in this manner will certainly convey an extremely unpleasant sensation, but it may be that this is a point of sentiment, and it need not here be discussed. ___

The Daily Telegraph (6 January, 1888 - p.3) HAYMARKET THEATRE. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play, “Partners,” and his curious and perverse treatment of the simplest possible story that ever occurred to novelist or dramatist, reminds one irresistibly of a cat engaged in the cruel process of killing a mouse. We all know what the cat does. It allows the mouse to run, pats it, paws it, tortures it, and takes an unconscionable time in putting the little creature out of its misery. Last night this process of slow torture was inflicted on a patient but keenly observant audience. Mr. Buchanan was the cat; his simple little plot was the harmless mouse; the cruelty was inflicted on the audience, who knew exactly what was going to happen, but were treated to a gambol that, as the long hours drew on towards midnight, proved a little wearisome. That this should be so, that the interest should flag, halt, pause, and eventually dwindle down to nothing, was inevitable when we calmly consider what Mr. Buchanan has done. He has taken the space of five long acts to tell a tale that could conveniently be told—concisely, sharply, and vigorously told—in two acts at the utmost. The story is as old as the hills, but it is none the worse on that account. Unfortunately the dramatist has in this instance hardly anything new to say about it. Nothing is gained by spinning it out, dotting the “i’s,” crossing the “t’s,” over-elaborating, underlining, insisting on the simplest dramatic points, running up to a climax and shirking it, putting the cup of excitement to our lips for the mere sake of dashing it away again. Thackeray has suggested with infinite force and excellent humanity, Daudet has elaborated with rare descriptive faculty, as a novelist is permitted to do, the story of man’s truth and woman’s weakness, the honest manly husband, the weak and badly influenced woman, the handsome, persuasive scoundrel, who play their parts with a difference, but a very slight one, in Mr. Buchanan’s new play. Mrs. Rawdon Crawley is discovered in her intrigue with the rich old Marquis of Steyne by her simple-minded and confiding husband, whose eyes are filled with dust; old Risler, the man of commerce is cheated out of his young wife’s love by his flashy and seductive partner, young Froment. Age and honesty are on this side, youth and temptation on that. It is one and the same permutation and combination of character. But, new or old, all depends on the treatment; and, regarded from the dramatic standpoint, Mr. Buchanan cannot be said to have handled it with his accustomed vigour or virility. He talks his subject away until at last he becomes positively tedious. ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (6 January, 1888 - p.2) MR BUCHANAN’S NEW PLAY. The production last night at the Haymarket, London, of Mr Robert Buchanan’s new play “Partners” was the first important theatrical event of the year. Mr Buchanan candidly confesses that he has borrowed his hero from the character of the elder Risler in Daudet’s famous novel “Fromont Jeune et Risler aine.” But the story in its central idea is a far older one. Mr Buchanan’s hero is, in fact, one of those characters familiar on the stage and in fiction, of an elderly man who has married a young wife. He implicitly trusts her, and with her and his little daughter he leads a happy life. He even launches out into extravagances, all well within his ample means. A house far above his own simple German tastes, horses and carriages, a man servant, who is the bane of his master’s life, and whom his employer addresses with much unctuous reverence, he has secured for her sake. It is his trusted partner who breaks up this happy menage. That partner is depicted as weak rather than wicked. He and the old German’s young wife were boy and girl together. Now, however, he has a pretty girlish wife of his own, the only daughter of the man who first admitted the present head of the firm into partnership. The junior partner squanders the firm’s money, and dares to tempt his senior’s wife. All this is clear enough in the first act, and the rest of a very long story is devoted to the somewhat tedious unravelling of the plot. The erring woman commits no actual sin. Even when her lover breaks into her house at midnight, she is saved by the sudden appearance of the child who has missed its evening kiss. At last when the storm breaks, and the senior partner discovers all and suspects more than has really happened, he casts his wife forth, relinquishes all his own savings to save the firm from ruin and in order that the daughter of his old benefactor, who first admitted him to partnership, shall be kept in ignorance of her husband’s perfidy he voluntarily accuses himself as chiefly to blame for the fall of the firm, dissolves partnership (by word of mouth), and sinks to his old position as clerk. This is the most original and the least satisfactory part of the play. In the fifth act, which contains a somewhat involved Christmas scene, dramatic justice is done. When “Partners” is much abbreviated, and when many excresences bordering on farce are struck out, it should assuredly prove a powerful, and it is believed will be a successful drama. At present it is somewhat unequally played, although the characters of the elderly husband and his young wife are quite safe in the hands of Mr Beerbohm Tree and Miss Marion Terry. Mr Brookfield has the part of a broken-down actor, and the child five years old was last night prettily played by Miss Minnie Terry, the little daughter of Mr Charles Terry, and niece of Miss Ellen Terry. ___

The New York Times (6 January, 1888) Robert Buchanan’s new play, “Partners,” was produced at the Haymarket Theatre to-night in the presence of one of the most brilliant audiences of the season. In an author’s note on the programme it was stated that the character of Dorgfeldt was partly founded on that of Risler in “Fromont Jeune,” by Daudet, but that the leading situations and most of the dramatis personæ were radically different. If by this Buchanan means that the names of the characters being changed and the wife white-washed makes the play radically different, it is so; but in fact it is in the main identical, and the resemblance to Daudet’s play is complete. It can be considered but an adaptation from the French author. The one string which is played upon is too fine to sustain the tension put upon it by the adapter, and what is considered the great scene of the play is lengthened by one-third more than was necessary or advisable. In its English shape the play is the old story of a confiding husband and a wife weak to the verge of guilt, except that the man who tempts her to dishonor her husband is his trusted partner. The usual misunderstandings produce a separation, which of course terminates as soon as one word of explanation is given. The play has some strong situations and many anti-climaxes, and is far from faultless in construction. It was respectfully listened to on account of the superb acting of Beerbohm Tree, who saved it from an early doom, although at the fall of the curtain hisses and applause were pretty fairly divided. If the piece ever succeeds it will require a great deal of compression and many alterations. ___

The Era (7 January, 1888) “PARTNERS” AT THE HAYMARKET. A New Comedy-Drama, in Five Acts, Heinrich Borgfeldt ... ... Mr H. BEERBOHM-TREE The Red Lamp having burnt itself out, Mr Robert Buchanan’s play named above was produced on the evening of Thursday last, in presence of a crowded audience, that included many notabilities representative of art, literature, and fashion. The author of Partners acknowledges some indebtedness to Daudet’s admirable story “Fromont Jeune et Risler Aîné,” and chiefly for his drawing of the character of his elderly hero, which is partly founded on that of Risler. Mr Buchanan has erred mainly on the side of over-elaboration. The simple story he has to tell—a story often told before Emile Augier wrote his “Gabrielle” and since—is not equal to five acts, and so, five acts being considered necessary, the interest is weakened by being long drawn out, and something like weariness comes of vain repetitions and a multiplicity of needless detail. The most striking instance of this arises with the close of the play, where the long-looked-for climax having been reached with the reconciliation of a husband and wife, who have been separated through the man’s faith and the woman’s weakness, people in whom we have felt little concern are dragged on to assist in creating an anti-climax over a bowl of punch. If, however, the play has some faults, it has many merits, and these assured it even more than a respectable hearing; for there were scenes that were replete with human sympathy, and that not only moved the house to hushed attention, but conjured tears to the eyes of those who are not always given to the melting mood. ___

The Sporting Times (7 January, 1888 - p.2) ON Thursday night Beerbohm-Tree produced Robert Buchanan’s new five-act play, Partners, at the Haymarket Theatre, and it gave me great pleasure to notice that the audience gave the work a thoroughly impartial and attentive hearing. At ten minutes past eleven o’clock the curtain had not risen on the last act, and for a few minutes the gallery whistled, plaintively, “We wont go home till morning,” but otherwise not a thing was said or done to disturb or disconcert the performers in any way. When the last curtain fell, however, the verdict of the impartial pit was very clearly expressed. Tree came forward and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, the author”—but the pit interrupted, “We don’t want him!” Despite this fact the fate of the play is by no means certain, for it has much in its favour to attract what are called “fashionable” audiences. The dresses of the actresses, for example, are in themselves a delight to smart ladies. The principal set scene is an artistic triumph of stage-carpenting, and above all the acting all round is particularly good. THE plot is thin to say the least of it. An old German marries a young and pretty wife. He goes away, and she flirts vigorously with his young and handsome partner. In a scene suggestive of Peril, she all but pulverises the seventh commandment, but is saved by the sudden intervention of her child. Then the old German returns, turns his wife out of doors, and says that he does not feel quite well. Subsequently he takes her to his arms again, and all ends happily. Three hours and a half of this sort of thing are a trifle wearisome; but, of course, it can be easily cut into proper lengths, and sold at a reduction later on. THE cares of management, multiplied by first night nervousness, naturally made Tree’s task a difficult one, when he attempted the portrayal of the old German. THERE was much in his performance of undoubted excellence, and it will be better still when he forces his humour a little less, and lets jokes about “Mr. Dickinson” come more unconsciously. His quiet pathos, too, I preferred to those scenes where he had to tear passion in tatters, and now and then he made queer, inarticulate noises that would have provoked the laughter of a less consistently fair audience. There are moments, too, when an increase of rapidity would enhance the force of the situations; but Tree no doubt knows all this just as well as I do, and probably by this time he has made the necessary alterations. Lawrence Cauntley was an impassioned lover, while the small part of a butler stood out most admirably in the hands of Charles Allan. Brookfield struggled nobly with a caricature nuisance that stopped the action of the story at every turn, and Kemble covered himself with glory as a confidential clerk. I wish to goodness Kemble would never try to be funny again, he is so excellently artistic, so manly, real and altogether perfect in parts that demand firmness, gentleness, and true pathos. OF the ladies, Miss Le Thiere did well as a sort of portly “Little Buttercup,” with admonition of “I told you so,” and “What did I tell you?” Little Minnie Terry was a capital child. Miss Janet Achurch looked nice and acted naturally, if a trifle despondently, and she wore sand shoes, I presume because she used to play in Sarah Thorne’s company at Margate. Miss Marion Terry wept and expressed the necessary emotion while acting most admirably in the Peril scene. Miss Gratton, in a very small part, was nice. The best performance of all, however, was that of Miss Gertrude Kingston, who, as Mrs. Harkaway, gave us a study of the modern woman of fashion that cannot be too highly praised. Her jerky walk, her short angular gestures, the quick, artificial, snappy voice, her every intonation proved the genuine artist and the keen observer. Nothing could possibly have been better, and I congratulate Tree on this admirable accession to his company. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (8 January, 1888 - p.5) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. HAYMARKET THEATRE. Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s talents as a “character” actor find special scope for their display as the hero of Mr. Buchanan’s new five-act comedy-drama, Partners, which was produced on Thursday evening. The part, that of Heinrich Borgfeldt, a middle-aged, uxorious German merchant, who speaks broken English, is acknowledged by the author to be founded on the character of Risler in Daudet’s Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé, a tale that, in other respects, has been of use to Mr. Buchanan in the construction of his play. The story is a simple one, turning on matrimonial discord, in which a young and sentimental wife, an old man’s darling, encourages the advances of her husband’s partner, a despicable sample of human nature, who, in addition to invading the sanctity of the old German’s home, brings the firm to ruin by a course of extravagance and dishonesty. The wife, who has never gone beyond the sentimentality of flirtation, is aroused to a sense of decency and duty by the influence of her child, but not before being seen in company with the would-be seducer by the injured husband, who has just returned from Germany, and been apprised of the junior partner’s two-fold perfidy. The husband separates from his wife, and with his child retires to a humble home, and bravely sets to work to reinstate his fortunes. In this resolution he triumphs, while, at a later stage, proof is afforded him of his wife’s innocence, and the piece concludes with a pretty picture of the kindly German merchant restored to happiness; and, notwithstanding his past wrongs and sorrows, left sound enough in heart to even breathe good wishes for the man so cruelly wronging him. The piece is an interesting one, and contains strong dramatic passages, but they are weakened by prolix dialogue, and the development of the story is somewhat slow. Mr. Tree’s portrait of Heinrich Borgfeldt is artistically and quaintly designed, and deservedly wins very hearty applause by its many touches of humour, pathos, and homely dignity; and above all, by the elaborate working out of a very distinct conception of a character which is original and impressive. The child, Gretchen, is charmingly acted by Miss Minnie Terry, and the erring wife, Claire, has a sympathetic representative in Miss Marion Terry. Humorous relief is given to the play by the introduction of an amusing personage—a Mr. Algernon Bellair, the father of Claire, retired from the theatrical profession, and according to his own account favoured by Melpomene, but misunderstood by the public, full of “quotes” from the old dramatists, and sorely impecunious—a part that is played with much quiet comicality by Mr. C. Brookfield. Mr. H. Kemble, too, as Parr, Borgfeldt’s faithful old clerk, performs with feeling and dignity. The other noticeable characters are acted by Miss Gertrude Kingston, Miss Le Thiere and Mr. Lawrence Cautley. The play has been placed on the stage with much artistic effect, and was received with favour. ___

The Referee (8 January, 1888 - p.2) DRAMATIC & MUSICAL GOSSIP. THE chief theatrical event of the week was the production at the Haymarket on Thursday of the long-promised play by Robert Buchanan—“Partners,” to wit—which was announced some time back under the name of “The Honour of the House.” Commencing at about 8.20 for 8, it was listened to with exemplary patience and devout attention until 11.15, when during the interval between Acts IV. and V. cries of “Time!” and snatches of “We won’t go home till morning” resounded from the upper regions. Still, good-humonr prevailed, and there was no attempt to find much fault with the piece until the end, which came about 11.35. Considerable condemnation was then mixed with the applause, and not wholly without reason. “Partners” is a play more remarkable for length than for strength. It has certainly not suffered from stage-managerial scissors. In point of fact, it is an actor-manager’s play, and, like all such, is overburdened with matter for the actor-manager. But the play’s chief defect is that it is pervaded by the strained sentimentality which somehow seems to get into all Mr. Buchanan’s dramas dealing with the age we live in. The leading character in “Partners” is Heinrich Borgfeldt, who is a German, and the senior partner in a wealthy English manufacturing firm. As on the face of it there seems no adequate temptation for this senior partner to belong to another nation, it is not unlikely that Beerbohm Tree instructed his author to cut the part to a German pattern—for obvious good and sufficient reasons. But to my tale. Borgfeldt has a pretty wife, Claire, who is less than half his age, and they have a little daughter, aged five. He worships both. Claire does not perceptibly enthuse towards her good-hearted husband, but this may be because (apparently) he has never washed his face or brushed his hair. Anyhow ,Claire encourages the attentions of the junior partner, Charles Derwentwater, a pretty fellow, but a consummate cad. Charles sheds priceless presents upon Claire, and by these and sundry other extravagances draws so largely on the firm’s finances that when Borgfeldt returns from Germany he finds that his partner has not only supplanted him in his wife’s affections, but has also seriously imperilled “the honour of the house.” Whereupon poor Borgfeldt pathetically calls upon old Parr, his head clerk, to produce the ledgers, day-books, &c., and straightway sets about saving the firm from ruin. After this the good old German goes home, and discovers his wife in Charles’s arms. But, mark you, Claire is not so bad as her husband thinks. We have already seen her in a scene of terrible temptation recalled to wifely duty and honour by the sudden appearance of her child—the first strong point in the piece, and one that absolutely saved the second act. Claire has since implored the charming Charles never to see her again, and she is really struggling with that quite too beautiful young man when her husband dashes in. Moreover, Claire has addressed a letter of remonstrance and farewell to the junior partner, which letter has fallen into the bands of Borgfeldt; but he—good, honest soul!—will not open a letter that is not addressed to him. If he had, he might have spared himself and family all the sufferings of the last two acts. Instead of which he drives his wife forth, and then makes himself a martyr by declaring to Charles’s young wife (the daughter of the house’s founder) that he (B.) is alone to blame for the commercial crash. The last act is, like the first, weak and inartistic. It is chiefly remarkable for some unnecessary Christmas business of the diluted Dickens type. If I remember aright, Buchanan was wont to denounce Dickens for this sort of thing. There is certainly more dilution than Dickens in the introduced geniality, and perhaps this accounts for it. Eventually Claire returns penitent, that letter which has lain about so long is opened, and the erring wife is forgiven. Here you might think the play finishes. Not a bit of it. Borgfeldt produces some rum-punch, which he shares out among all and sundry, and, after some more cackle, drinks to all assembled and to his absent friend Charles, whom he seems to miss. The author of “Partners,” who sets forth upon the bill of the play that “the character of Heinrich Borgfeldt has been partly founded on that of Risler in ‘Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé,” has, in adapting portions of Daudet’s book for the English market, only succeeded in presenting an unpleasant story in a very strained style. Beerbohm Tree, as Borgfeldt—a sort of character often played by Ben Webster—showed on the whole considerable power, and once or twice was very pathetic; but he had so much to say that before the evening was over the part became “as tedious as a king.” Quite half of it should be cut out. Also, his speech was much too foreign for one supposed to be so long resident in England. Germans of that sort don’t say “mein” this and “mein” that. Mr. Cautley was full of fire and passion as Charles, the junior partner. Mr. Kemble, as the head clerk, Parr, played with a repose somewhat foreign to him, and scored all the time. Mr. Brookfield is to be commiserated on having to waste his talent for character acting on an utterly conventional and absurd rôle of the Crushed Tragedian type. He played well; but the part is no use. Mr. Eric Lewis also had a stupid character. The ladies were not strong. Miss Marion Terry had but few good moments, and those only where the character carried her out of herself. For the rest, she was mournful. So was Miss Achurch, who intoned her lines. Miss Le Thiere did her best with the character of a good-hearted busybody with much too much to say. The most natural of the young ladies was Miss Emilie Grattan, who played the faithless partner’s faithful wife, and little Minnie Terry, as the child Gretchen. The music and the mounting deserve high praise. This (Saturday) afternoon I have been informed that “Partners” has now been so judiciously curtailed that the performance concludes before eleven. Also that there will be a new front piece put on next Thursday, and that “Partners” will then commence at half-past eight. It has been decided to give a morning performance every Saturday. ___

The People (8 January, 1888 - p.4) THE THEATRES HAYMARKET. A first night at the Haymarket is always a pleasurable anticipation to lovers and students of the stage, for the reason that it has long since become a tradition of this house, the recognised headquarters of pure comedy and drama, to produce the best procurable pieces in the best possible style. But whether “Partners,” the new comedy-drama written by Mr. R. Buchanan, and brought out on Thursday night by Mr. Beerbohm Tree, will take rank among the highest presentments of this theatre, time alone will tell. The critical verdict upon the performance, taken purely upon its merits, cannot, however, be altogether so favourable as that with which in the main the good-natured audience greeted the play. The plot of “Partners,” which follows that of Daudet’s novel, “Fromont Jeune et Risler Aine,” quite closely, save in its ending, presents a middle-aged German merchant, who has worked his way up from the position of clerk in the office of the eminent London house of which he is the head. This simple-minded trader has for junior partner a young fellow less honest in nature though more attractive personally than himself, who, framed to make women false, takes a base advantage of his senior’s absence on business abroad not only to dissipate the capital of the firm to the point of ruin, but to attempt that of the young wife of his worthy but somewhat humdrum partner. from this pollution the lady, a former sweetheart of the junior merchant, is saved, after a moral struggle, at the crucial moment of yielding to his embrace, preceding a still graver fall, by the sudden apparition of her little daughter. The husband returns to his office to learn from his old and confidential chief clerk of the double breach of trust committed by his partner. Crushed at hearing of this simultaneous wreck of the affections of his heart and the commercial honour of his house, the hardly used merchant, before returning home to confront his errant wife, sits down sternly over his ledger with a view to ascertain the extent of the defalcations, in order that by work and sacrifice of all he possesses, he may retrieve, if possible, the failing credit of his firm. That done, at a late hour of the night he wends his way home, arriving there at the moment his wife is struggling for the second time to free herself from the arms of her treacherous lover. Believing her to have actually fallen, the indignant husband passionately refuses to hear any excuse from the wretched woman, wrenches the wedding ring from her finger, and dismisses her straightway from his house. In the humble cottage, to which, with his little girl, the merchant has retired, the truth of the actual salvation of his wife’s honour by the unconscious agency of their child is brought home to him through the perusal of a letter, written by the mother to the baulked seducer, in which, after upbraiding him for his cowardly assault upon her honour, she bids him never to enter her presence again. This letter, intercepted by the confidential clerk, and handed by him to his master on the night of his return from abroad, the merchant, from an over nice sense of delicacy in the circumstances, has refused to open, although its superscription is in the handwriting of his wife, simply because it is not addressed to himself. The perusal of the document leads up to the introduction of the compromised, but not absolutely guilty, wife, who receives the forgiveness she implored in the arms of her husband. The play, though wanting freshness of incident and characterisation, might be interesting enough to engage the attention and hold the sympathies of an audience were its story not so intolerably long drawn out, lasting, as it did, from eight o’clock until half past eleven, three and a half mortal hours. At least an hour must be “sawn out of the acts”—as poor H. J. Byron phrased it—if “Partners” is to be made attractive. In his impersonation of the Anglo-German merchant, Mr. Beerbohm Tree as is usual with him, presented by his excellent make-up a perfect character to the eye. In respect of the acting, like all Mr. Tree’s assumptions, this, his latest effort, beginning admirably, dwindled in interest and effect as it developed by reason of a persistent monotony of expression. Without the brightening relief of humour, save in one welcome touch, the German merchant is throughout so sentimental under all circumstances as to become a maunderer. Mr. Tree, failing to differentiate artistically, misses his opportunities. For instance, upon the news of his double calamity being broken to the merchant, he expresses natural emotion at his partner’s perfidy in exactly the same whining and irresolute tone as that exhibited by him at the infidelity of his wife. The weakness of the breakdown under the domestic trial, instead of being identical with, should be contrasted against, the commercial crisis, shown in the sudden change, when the business difficulty is approached, to a quick, firm, incisive manner, from which every trace of sentiment should disappear. Mr. Tree has yet to learn the value of light and shade in feeling as induced by varying motives and displayed in artistic contrast. As the respectable old clerk, Mr. H. Kemble acted naturally. The part of the unprincipled junior partner was rendered as little repulsive as possible by the quiet earnestness of Mr. L. Cautley. As a bombastic retired actor—a cross between Captain Costigan and Vincent Crummles—Mr. C. Brookfield exhibited much artistic humour, which unluckily ran to waste because the character, belonging in no way to the plot, was simply patched upon it. The young wife, as delineated by Miss Marion Terry, proved to be a graceful and sympathetic character, but acted, as it seemed, with less fire and intensity of passion than has heretofore been exhibited by this lady. Miss Achurch played a devoted sister of the peccant wife with sincerity; but as regards tone and appearance, upon a lower social level. The repulsive part of a wicked woman of fashion was enacted by Miss G. Kingston, a débutante, with faithfulness to the character and a certain distinction, though wanting in the repose of manner, ease of movement, and accomplishment of finesse which only stage practice can give. Minor parts were taken effectively by Messrs. Eric Lewis and Stewart Dawson, Miss Le Thiere, Miss E. Grattan, and a little daughter of Mr. Charles Terry, who made her entrée to the stage with pretty artlessness as the merchant’s child. At a call for the author, given with some evidences of dissent, Mr. Tree stated Mr. Buchanan was not in the house, but he would convey to him the approval “generally expressed by the audience.” ___

The Stage (13 January, 1888 - p.14) HAYMARKET On Thursday evening, January 5, 1888, was produced here a “new comedy-drama,” in five acts, written by Robert Buchanan, entitled:— Partners. Heinrich Borgfeldt ... ... Mr. H. Beerbohm-Tree That Mr. Buchanan has succeeded with his latest effort cannot be admitted; that he has, on the other hand, given a clever young actor a character in which a legitimate triumph has been secured is beyond doubt. Mr. Buchanan confesses that in his new play are “numerous suggestions” that have been taken from Daudet’s story, “Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé.” With these we have nothing to do. The question is, what is the play like that has just been produced with such perfect stage management at the Haymarket Theatre? Is it a good acting play—one that will draw? Before answering this it will be well briefly to run through the plot of Partners. Heinrich Borgfeldt, a German, has been raised from the position of head clerk in an English merchant’s office to that of a partner. He is wealthy, and the soul of honour; his one idea in life is to do his duty, to keep the credit of his firm sound, its name untarnished. Borgfeldt has for partner in his business Charles Derwentwater, who is his very opposite in every way. Borgfeldt is old, and cares not for the gaieties of life; he is frugal in all things, save in securing the happiness of his young and beautiful wife, Claire. On the other hand, Derwentwater is young and handsome, a spendthrift, full of the pleasures of life, and is what is commonly called “a ladies’ man.” The result, according to the French school of thought, is evident. Derwentwater neglects his own wife, a simple, innocent girl, and becomes enamoured of Claire. She, poor foolish woman, is so fevered with his seemingly devoted admiration (chiefly shown by his presents of diamonds, bought at his firm’s expense), so mistaken with regard to her own husband, thinking his necessary attention to business neglect of her, that she half accepts her would-be destroyer’s vows, and for a time basks in a summer madness, which she thinks passionate love. In an evil moment Claire has listened to the advice of a friend—Mrs. Harkaway, “a woman of fashion”—who, in pique at Derwentwater’s turning from her own openly expressed admiration, soon manages to convince Claire that flirtation is not wicked so long as the husband remains in ignorance—that sin is not sinful unless found out. Weak-minded Claire, therefore, instead of boldly telling her husband all and turning her back upon Derwentwater, meets the latter half way, and without committing actual sin brings trouble and disgrace to her once happy home. Borgfeldt, owing to his firm having become involved in financial difficulties, undertakes a journey to Germany that he may secure money. Unsuccessful, he returns home to find his firm ruined, and seeming clear proof that during his absence his young wife has become the prey of his hitherto trusted partner. He is given a letter that has arrived at the office written by his wife and addressed to Derwentwater. This, which would explain all, he refuses to read, but instantly turns his wife out of his house. In the last act we find the old man living in comparative poverty, though he has once more placed the firm on a sound commercial basis. It is Christmas Eve, and as from outside his cottage he hears the message of “peace and goodwill to men,” carried to him by carol singers, the old man’s heart yearns that his wife, if innocent, may be with him once more. Claire, through the instrumentality of a mutual friend, Lady Silverdale, does return—the letter the husband refused to open is now read, proves her to be guiltless and faithful to her husband, and as the bells ring and the carol singers break out afresh, Borgfeldt takes his wife to his arms, and the curtain falls. This it will be owned is a simple tale that needs but simple and straightforward telling to make it successful. Instead of confining his play to two acts—quite sufficient—Mr. Buchanan makes the serious mistake of dragging the plot out through five weary acts that are crowded with unnecessary language, and hampered at every turn with anti-climax. True, the story of Partners is old—what of that? Old plots can be so re-dressed and clothed with rich ideas and beautiful language as to appear fresh and original. But no, Mr. Buchanan does not venture beyond well-beaten ground, his language is never above the average, his incidents are commonplace and tiresome. Take, for instance, the last incident in the play—the reconciliation of husband and wife. A dramatist who knew his work would have brought down his curtain upon the embrace. Mr. Buchanan, with a positive fondness for anti-climax, introduces punch drinking, and ruins the principal character, Borgfeldt, by making him drink to “Charles, my partner,” the very man who has tried to seduce his wife. Then again, in the office scene, Borgfeldt’s break down with grief should end the act, but Mr. Buchanan brings him back to common life by forcing business matters upon him—matters that should be finished with before the crushing news of Claire’s supposed sin is told. True that Mr. Buchanan has provided Mr. Beerbohm-Tree with a fine part in Borgfeldt, but he has also so constructed the character that few actors could gain for it the sympathy necessary for the success of the entire play. We have pointed out two instances that go far to rob the character of all pathos; a further one is where Borgfeldt, hearing the bells ringing and the carols sung, recalls the past. He is permitted but a moment to mark what there is of pathos in the incident before he is brought back again to the commonplace by an overbearing and quite out-of-the-picture character, “ a retired actor.” This character is conceived on the lines of the good old lend-me-half-a-crown-pay-you-to-morrow Micawber style, false to the state of the modern actor’s career and a blot upon the profession of the stage. It is very interesting to see what Mr. Beerbohm-Tree has done with this strange creation of the author’s, this Heinrich Borgfeldt. All who know this actor need not be told that the character is perfect as regards make-up and that his German-English accent is also true to nature. We have always considered Mr. Tree clever, we are now bound to admit that he has genius. Borgfeldt in his hands is a great, a noble conception brought to life and richly endowed with all the actor’s art. What faults are to be found with this performance are, we think, entirely due to the author. Mr. Tree has been censured for over-elaboration. All we noticed on the first night was apparently brought about by the over-anxiety of the actor in trying to render reasonably probable the inconsistencies and extravagances of an imperfectly drawn character. Mr. Charles Brookfield is admirably suited as Mr. Algernon Bellair, the retired actor, to whom we have referred. It is not Mr. Brookfield’s fault that Bellair becomes a nuisance at times, that his presence in certain scenes is destructive to art and to the general welfare of the piece. Mr. Brookfield does wonders with the part, and clearly proves his right to be looked upon as one of the most clever of our young actors. Another fine example of the actor’s art comes from Mr. H. Kemble, who as the head clerk, Mr. Parr, from the crown of his head to the sole of his foot, is true to life in every detail. The same remark applies to the Dickinson of Mr. C. Allan. Can anything be more amusing than the scenes between simple-minded Heinrich Borgfeldt and his grand butler Dickinson? They are splendidly funny; Mr. Allan plays like a true artiste. Mr. Laurence Cautley looks handsome and fascinating as Charles Derwentwater, but his acting wants heart and soul; not once did he on Thursday make us feel that Charles really meant to win Claire’s affections so that he might ruin her body and soul. Mr. Eric Lewis makes some amusement out of a small part, that of a henpecked husband; Mr. Stewart Dawson is fully competent as a doctor, and the two clerks are naturally played by Messrs. Harwood and Rodney. It is a rather difficult matter to speak of Miss Marion Terry’s Claire. Miss Terry is not the right lady for a part such as this. Her scenes with Mr. Cautley were on Thursday distressingly like rehearsals, there was little trace of that art that conceals art. In her scenes with Mr. Tree, Miss Terry acts as if Claire were a friend of Heinrich’s rather than his “darling frau.” Miss Achurch has little to do as Alice. She, however, looks the gently loving sister, and acts naturally. Miss Emilie Grattan, who has become quite a woman since last we saw her, is a pretty and innocent-looking Mary, and does all that is possible with the part; Miss le Thiere gives a well matured and most acceptable portrait of Lady Silverdale, while Miss Gertrude Kingston, a young lady who has wisely been gaining some experience in the provinces, gives an admirable study of Mrs. Harkaway. Her walk, talk and manners are well in keeping with this strange character; for Mrs. Harkaway dresses from head to foot in flaring red silk, she wears a single eyeglass, she whistles when Claire talks to her, she stands with her back to the fire after the fine old English gentleman style, she plays upon the piano like a woman without soul or manners, she snubs her little husband, and reduces him to the position of a pet dog; and, when leaving her friend’s drawing-room, she sneers at its occupants, and glories upon having brought misery upon its owner. To play such a dead-against-the-audience character, and succeed in gaining their applause, speaks well for Miss Kingston’s ability. A little child, Minnie Terry, daughter of Mr. Charles Terry, plays the tiny part of Gretchen with winning freshness. Perfectly free from all approach to staginess, this pretty infant gives her lines with such clearness and point as to make us think she has a natural gift. Great taste and liberality have been called into use over Partners. Nothing like Mrs. Borgfeldt’s drawing-room—for richness of design and perfection of detail—has ever been staged. The office scene in Act IV. also appears to be perfect as regards detail. The music introduced, “The Holly Berrie,” composed by Hamilton Clarke, is strictly in keeping with the old style of Christmas carol, while the incidental music, chiefly built upon German airs, is also from the same pen. Partners has, we understand, been in rehearsal a very long period, under the stage management of Mr. Edward Hastings, to whom is due the praise that the staging of the piece naturally brings forth. That Mr. Buchanan’s piece will succeed is pretty certain, and it will owe its success to its mounting and representation. ___

The Athenæum (14 January, 1888) DRAMA THE WEEK. HAYMARKET.—‘Partners,’ a Comedy-Drama in Five Acts; THOSE who adapt French novels to the English stage are not much better off than their brethren who transfer plays “ready made.” Similar difficulties have to be faced in both cases, and resort is ordinarily had to the same expedients. It would not be fair to class Mr. Buchanan among adapters. The central figure of his play is the same as in the ‘Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé’ of M. Daudet. He has, however, departed widely from his original, and combined with much that is in that remarkable novel much for which he himself is alone responsible. None the less his difficulties are those of the ordinary adapter. Dealing with a story of feminine vice and masculine probity, he has been compelled to leave out half, and in so doing destroy the moral and the plot. That the Sidonie of the original could not be presented on the English stage may be granted. To substitute, however, for this grim type of feminine depravity the femme incomprise, of whom the world begins to pall, and to furnish a happy ending is to spoil a fine conception. Mr. Buchanan is entitled to claim that he has obtained a fairly sympathetic and, it may ultimately prove, a successful play. His work, however, is most uneven, and much of it infirm in construction. A psychological study at the outset, it ends like the mildest of domestic comedies. To call in the play-bills the last scene Christmas, and to surround the action with holly and mistletoe, is, perhaps, the most serious mistake that is made, since from the outset it tells the spectator who reads his play-bill that the issue is happy. ___

The Mercury (14 January, 1888 - p.2) THE BOUDOIR. . . . The new play at the Haymarket is all Mr. Beerbohm Tree, and it cannot be said to be Mr. Tree at his best. Mr. Tree has never been an emotional actor, and the part which he is now playing can produce no effect unless played by an actor who is wholly devoid of self-consciousness. Some very manifest absurdities in the character might then be overlooked, such as the uselessness of the head partner resigning the helm, and thinking to benefit the firm by resuming his place as a humble clerk. Moreover, Mr. Buchanan makes the elderly hero of “Partners” a kind of spoilsport, twice breaking up agreeable parties under his own roof. The scene in which he demands his wife’s jewels to sell for the good of the firm comes dangerously near the ludicrous; he did not give her the jewels, so clearly has no right to ask for them. The knowledge of life and manners on the part of the author seems ludicrously deficient; for what can we think of a lady described by one of the characters as “constantly leaving her box and interviewing her acquaintances in the stalls”? We can only say (as I heard a spectator in the stalls remark) “Quaint lady!” and pass on to other matters. In person Mr. Tree has undergone a complete transformation, and nothing could be more unlike the stealthy detective [ ... ] picturesque Gringoire of the “Ballad-monger” who pleads his cause with his lady-love while the soft strains of Maude Valérie White’s “Devout Lover” are played by the unseen orchestra. This time Mr. Tree impersonates a German, and his appearance and accent could scarcely be more perfect. As a study, the impersonation is very remarkable, but it smells of the lamp, and fails to touch the heart. It is, perhaps, the author’s fault more than the actor’s that Heinrich Borgfeldt is so silly and unsuspecting that he fails to gain our sympathies. ZINGARI. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (14 January, 1888 - p.10) |

|

|

MR. H. BEERBOHM TREE bids fair to do for Comedy what Mr. Henry Irving has done for Tragedy. This clever young actor had already made his mark as a delineator of character unsurpassed for power of individualising, as witness his totally opposite creations, sketched above, of the original comic Curate in “The Private Secretary” and Macari, the cold-blooded villain in the weird drama of “Called Back.” Since Mr. Tree has had the good fortune to succeed to the managership of Mr. and Mrs. Bancroft’s handsome house in the Haymarket he has well sustained the finish and truth to nature of his own personal representations, and has placed on the stage the new pieces intrusted to him with a care and a magnificence which well entitle him to rank with Mr. Irving for artistic excellence. These distinguishing merits are conspicuous in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new comedy-drama, “Partners,” which does not appear to have escaped hissing on the first night, but which on a subsequent evening, the piece having been judiciously compressed, went admirably. The central character and backbone of the play are derived from M. Daudet’s powerful romance, “Fromont Jeune et Risler Aîné.” Heinrich Borgefeldt, the character in question, is a middle-aged German, whose probity has won for him the senior partnership of his firm, a position which has gained for him also a fair young wife, Claire. But Claire evidently finds the attentions of the junior partner, Charles Derwentwater, congenial. Hence the tears of the German, who returns from his travels to find his firm ruined by Charles’s extravagances on behalf of Claire, and to imagine, on what appears to be good evidence, that his wife is about to elope with his seductive young partner. An old unopened letter convinces him of his error, and it is the means of reconciling Heinrich and Claire Borgefeldt in a touching Christmas scene. Heinrich Borgefeldt is one of Mr. Tree’s most artistic assumptions, and will tell the more when he infuses a spark of fire into the acting here and there. Mr. Laurence Cautley makes a fervid lover; and Miss Marion Terry a charmingly-graceful and natural Claire; while the Mrs. Harkaway of Miss Gertrude Kingston is decidedly clever, the Lady Silverdale of Miss Le Thiere is capital, and nothing could be more winsome than Miss Achurch’s Alice Bellair (whom the author ought to have given a sweetheart), little Minnie Terry’s Gretchen, or Miss Emilie Grattan’s Mary. Mr. H. Kemble is admirable as the confidential head clerk, Mr. Parr. Much laughter is occasioned by Mr. Chas. Brookfield’s humorous and true portrait of an old-school tragedian, Mr. Algernon Bellair; and justice is done to minor low-comedy parts by Mr. Eric Lewis and Mr. C. Allan. ___

The Illustrated London News (14 January, 1888 - p.7) THE PLAYHOUSES. It has been officially announced that Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play, “Partners,” at the Haymarket, has been so cut, altered, shortened, and improved since the “first night” that few would recognise it as the same play. There must surely be something radically wrong with our English system of rehearsals that allows a new venture to be jeopardised in this fashion. Presumably a stage-manager has a watch, and can tell—or ought to tell—to a second how long the performance will take at night. Where is the judgment, where the directing and governing power that passes and admits and consents to scenes that are obviously irrelevant, and pages of dialogue that are palpably unnecessary? Why should it be necessary for a first-night audience—mostly composed of experts—and for critics, whose experience is not without value, to point out when too late the little defects of a play what do it such incalculable mischief when submitted in a raw, unfinished, and incomplete state? The stage-manager in this instance stands condemned. We do not know, or care, who he may be. If he can with ease cut out a good hour from a play on the second night, and bring down the curtain sharp at eleven, then his want of judgment or decision is gravely at fault when he passes a play for the press full of overburdened scenes and redundant dialogue. The failure of “Frankenstein” at the Gaiety, on the first night, was due to inefficient and reckless stage management. The authors, the actors, the whole scheme of the play, were allowed to go by the board in order to allow the stage manager to indulge in a craze for overdecoration, overadornment, and unnecessary display. Such stage management as that is literally worse than useless. It argues an absolute want of familiarity with the text, an indifference to the relative and component parts of a piece, an absence of that supervision and grasp of effect that should be the province of the stage manager as much as of the professional critic. A stage manager who looks to one scene, and one scene alone, or to one actor and one actor alone, to make the success of a play, is destitute of the rare quality of experience. He does not understand the public whose tastes and idiosyncrasies he should study. ___

The People (15 January, 1888 - p.4) ——“Partners,” at the Haymarket, having been judiciously curtailed by the author since the first night, is now played nightly to large and enthusiastic audiences. The receipts on the 7th inst. were the largest ever taken under the present management. Morning performances will take place every Saturday. ___

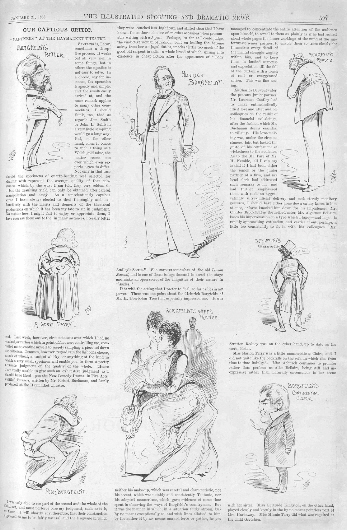

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (21 January, 1888 - p.19) OUR CAPTIOUS CRITIC. |

|

|

The Echo (26 January, 1888 - p.1) Who was it that wept?—The London Correspondent of the New York Herald thus writes about the production of Partners at the Haymarket on January 6th:—“All the critics of the London Press were present, and, whatever they may see fit to write about the actors or the play, I can testify that several of them heartily applauded, and two of them stealthily wiped away tears in the last scene between Mr. Tree and Miss Terry.” And what was the matter with the man who saw them crying? ___

The Academy (28 January, 1888 - No. 821, p.67-68) THE STAGE. “PARTNERS” AT THE HAYMARKET MR. BUCHANAN’S “Partners,” produced at the Haymarket, and already, I was glad to find, a good deal amended and shortened since the first night, is really a very free adaptation of what is perhaps after all Daudet’s best novel. The play owes more to Froment jeune et Risler ainé than Mr. Buchanan thinks. In the record of his obligations he aims to be very precise, but he ends by being insufficient. What he has not managed to transfer or convey is the brightness of the story. The whole Delobelle group, for instance— tragic actor who has nothing in him, devoted wife, and that daughter, Desirée, who is as a figure torn from a page of Dickens—is but poorly represented in “Partners” by the single character of Mr. Bellair. Mr. Buchanan may say it does not aim to be represented at all, yet the idea of the neglected tragedian who has no value is assuredly from Daudet at a distance. But the originality of treatment which Mr. Buchanan, in his “Author’s Note,” endeavours to imply, refers chiefly, we suspect, to the fact that whereas M. Daudet let his heroine go over the precipice, Mr. Buchanan is careful to pull her up on the brink. Hence, greater acceptability, no doubt, to the British public; and hence, too, some loss of naturalness in the story. Mrs. Borgfeldt’s substantial innocence would have been in all likelihood established much sooner in real life than in Mr. Buchanan’s fiction; and—not to speak of anything else—in real life that letter which attests her incorruptibility would not have taken so long to open as it does at the Haymarket Theatre. Mr. Buchanan may nevertheless have something to say in defence—even in artistic defence—of the course he has pursued. Unfortunately, however, he cannot rebut the accusation of having produced a piece which, even now that it is shortened, has about it too large a measure of dulness. Interest of a kind it has also—one character is thoroughly studied—the sombreness is at certain times very effective. There are two or three fine scenes. But, on the whole, it must be uphill work for the actors; and without the aid of some very good acting indeed, the piece would have fallen to the ground. At present, what keeps it going is the impressive, and at times affecting, performance of Mr. Beerbohm Tree, and the admirable support which he receives from two or three of those who are associated with him. How long these things will suffice with a public moved by so many impulses—affected now by caprice, now by fashion, and now, one hopes, for a change, by sober reason—it is safest not to venture to prophesy. FREDERICK WEDMORE. _____

|

|

|

|

|

|

|