|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 15. Lottie (1884)

Lottie * Lottie was produced at the Novelty Theatre when Robert Buchanan and Harriett Jay were both in America. There was no author’s name attached to the play but seeing as it was an adaptation of Harriett Jay’s novel, Through the Stage Door, the subsequent attribution to Robert Buchanan seems fairly certain, as is Harriett Jay’s involvement in the adaptation.

The People (9 November, 1884 - p.10) When the comic opera of “Polly” is transferred to the Empire on Saturday, the 15th inst., the stage of the Novelty will be occupied by a new and original farcical comedy to be entitled “Lottie.” The piece is compounded of curious dramatic ingredients, presenting inter alia a learned doctor, obviously clerical, since he makes his way behind the scenes of a theatre for the ostensible purpose of converting to the true faith in divinity, as preached by him, the poor players, who, strange to say, through the agency of a tragic actress, reverse the process by converting the doctor to a still truer faith in morality as exemplified by them. This sounds like the makings of a serious stage homily, scarcely consistent as it would seem with farcical comedy, as the piece purports to be, but nous verrons. All depends upon the treatment. The chief parts will be played by Miss Fanny Robertson, Miss Lydia Cowell, and Mr. Harry Nicholls, whose assumption is that of a music hall singer. The authorship of this production, which is dual, is to be kept anonymous as regards one writer, the other being, as it is whispered, Mr. Horace Sedger, husband of the manageress of the Novelty, pleasantly known to the public under her professional name of Miss Nelly Harris. ___

The Glasgow Herald (17 November, 1884 - p.9) A new piece, “Lottie,” announced at the Novelty last night is postponed till Thursday. The author’s name is not given, but it is reported (although on insufficient authority) that the piece is an adaptation by Mr Robert Buchanan. That gentleman has, however, recently been, and it is believed is still, in the United States. |

|

|

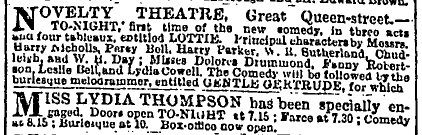

[Advert for first night of Lottie from The Times (20 November, 1884).]

The Times (21 November, 1884 - p.10) NOVELTY THEATRE. Miss Nelly Harris, despite her vigorous and plucky management, has not yet contrived to break the temporary spell of ill-luck that seems to have fallen upon this theatre. The new comedy Lottie produced last night will not help to retrieve the misfortunes of Polly. On the contrary it has not even the attractiveness of that piece, but recalls by the crudity of its workmanship and the feebleness of its story some of the dreariest souvenirs of the oldest playgoer. The author withheld his name from the bills, and in doing so gave proof of better judgment than his handiwork displayed. In response to the applause of what seemed to be a claque in the pit Mr. Harry Nichols, who had been playing in the piece, came forward and intimated that the author would be communicated with, but when the cry was raised “Who is he?” he only vouchsafed the dubious information that he “had never heard of the gentleman.” If Lottie is a favourable sample of his dramatic ability, it is not likely the public will want to hear of “the gentleman” again. The story of the piece resembles that of Caste in so far as it deals with one of those acquaintances made at the stage-door which ripen into marriage. It contrasts the humble hearth of an actor of the “legitimate” and his family with the interior of a country mansion, whither a young lady who does “juvenile lead” is conducted by an aristocratic admirer in virtue of le bon motif. But the subject is treated with such a lack of truth and with such feebleness of purpose that it gets no hold of the spectator’s sympathies. The author writes from the stage point of view. His theatrical personages are all estimable to the last degree, and contrast favourably for the most part with the “swells” with whom they come into contact. Lottie’s contemplated marriage with Colonel Sedgmoor is, indeed, retarded for a whole act by the unworthy scheming of the colonel’s sister and the no less unworthy conduct of another officer and gentlemen in seeking to compromise his friend’s fiancée. This is a wide departure from Caste, but there are strong suggestions of that piece in Lottie’s having a sister, also in the “profession,” who keeps company with a comic young man connected with the music-halls. In addition to the latter character, the comic element is represented in a clerical gentleman of indefinite rank in the Church—his legs being suggestive of a colonial bishopric, while his headgear is of a purely lay type—who “penetrates behind the scenes,” and who may be strongly suspected of writing theatrical testimonials. In the last scene we are introduced to the green room of a theatre where several of the characters promenade in costume, as in Adrienne Lecouvreur, Lottie, for example, appearing in the garb of Ophelia. The acting does full justice to the piece. Miss Lydia Cowell plays Lottie with an amount of brightness and feeling which in a stronger part would command attention. She is cleverly seconded by Miss Leslie Bell. Mr. Harry Nicholls for his part draws an amusing sketch of the lion comique, who works “three ’alls” of an evening; and half-a- dozen other ladies and gentlemen make up a picturesque and efficient cast. ___

The Morning Post (21 November, 1884 - p.5) NOVELTY THEATRE. “Bother art,” says one of the characters in “Lottie,” the new and original comedy with which this theatre reopened last night, and the unknown author acts up to the idea by allowing the dramatic phrase of it to be very considerably bothered before the final fall of the curtain. The effect is unfortunate, since it greatly weakens an artificial story of the stage, which stands sorely in need of artistic finish and refinement. Some memory of “Caste” is awakened when we find a gallant colonel and a timidly vicious captain visiting the humble home of the young actress, Lottie Fane; and the first act ends with a telling situation on Colonel Sedgmoor introducing Lottie to the Captain as his affianced wife. The misunderstanding that follows delays the anticipated marriage, without in any marked degree enhancing the interest of the piece. A plotting sister of the Colonel’s works much mischief, and the half-hearted treachery of the Captain sunders the lovers for a time. Then all find their way to the stage door, and within the supposedly mysterious precincts of the “green-room” the Colonel renews his suit and wins the young actress. For the judicious handling of a plot of this simple kind keen dramatic perception, coupled with delicacy and taste, is needed; but these qualities are not brought into play. Though the somewhat coarse humour of “Lottie,” with its exhibition of theatrical manners and customs and plentiful admixture of professional talk, called forth many a laugh, the performance could not but make the judicious grieve. Miss Lydia Cowell depicted the heroine as a too homely character, with no spark of pride; yet in the final scene there came a touch of feeling that deserved and commanded cordial recognition. The burden of the comicality fell to the share of Mr. Harry Nicholls, who emphasised the offensive familiarity of a music-hall singer, known as the “Great Jinks.” A clergyman who visits the theatre for the first time was rendered with quiet drollery by Mr. Percy Bell. Mr. Sutherland had an unthankful part in the Colonel, while Mr. Day was an unusually stiff-necked villain. The three ladies, Miss Fanny Robertson, Miss Dolores Drummond, and Miss Leslie Bell, made the most of the material at their command. On the conclusion of the play loud calls were raised for the author, when Mr. Nicholls appeared and thanked the audience on his behalf, but in answer to a demand for his “name” said he had never heard it. The comedy is, we believe, an adaptation of Miss Harriet Jay’s story, “Through The Stage Door.” In consequence of the illness of Miss Lydia Thompson the burlesque was postponed. ___

The Standard (21 November, 1884 - p.2) NOVELTY THEATRE. One of the crudest and feeblest pieces the stage has lately seen was produced at the Novelty Theatre last night under the title of Lottie. The subject is that which was treated by the late Mr. T. W. Robertson in Caste, except that Eccles here becomes a virtuous father. Sam Gerridge is turned into a comic singer, and the humour and pathos which were so charmingly interwoven in Caste have no place in Lottie. A weak-minded Baronet, Sir Robert Sedgmoor, falls in love with Lottie Fane, an actress, who resembles Esther Eccles in loving above her station, and in possessing a volatile younger sister after the model of Polly Eccles. Sedgmoore penetrates to the Fanes’ lodgings, engages himself to Lottie, and is then summoned to India. He leaves instructions with his sister that Lottie Fane is to be treated as the mistress of his house till he can come back and marry her; and the audience is invited to sympathise with the young lady in this position. Her own conduct, however, is open to misconception as regards what looks like a vigorous flirtation carried on with Sir Robert’s ward; she also invites the comic singer and her sister to the house, where they comport themselves in such a way as to emphasise the undesirability of a close union with the Fane family and connections. Miss Sedgmoor’s well- founded objection to her brother’s marriage carries her to unjustifiable lengths, no doubt; but she is sorely tried. Lottie, however, is persuaded to leave the house in company with Sir Robert’s ward. Sir Robert returns from India to find her gone, and grief is understood to ensue. He follows Lottie to the green-room of the theatre, where she is playing Ophelia, and her sister is representing an indefinite male character in tights. There the conventional reconciliation takes place, and the “new and original comedy” is at an end. There is, of course, no scope for successful acting in such a piece as Lottie. Miss Lydia Cowell plays the heroine as well, perhaps, as the untoward circumstances in which she is placed permit. Miss Leslie Bell overdoes the vulgarity of the heroine’s sister. Miss Drummond represents the unfortunate Miss Sedgmoor, and Miss Fanny Robertson as Mrs. Fane shows some glimpses of appreciative humour in the character of a tragic actress who carries her profession into every-day life. Mr. H. Nicholls finds little scope for the exercise of his drollery as the comic singer, Jinks. Mr. Sutherland acts naturally as Sedgmoor; Mr. Percy Bell is a clergyman who does duty as the comic singer’s butt, and other parts are filled by Mr. H. Parker and Mr. W. H. Day. As usual in bad plays, some of the lines are curiously mal à propos, as when Lottie, discovered by Miss Sedgmoor in the midst of a violent flirtation with Sir Robert’s ward, says innocently, “Why does she watch me so?” Mr. Edgar Pemberton’s amusing skit on melodrama, Gentle Gertude, was to have followed Lottie, but owing to the indisposition of Miss Lydia Thompson it could not be given, and A Rough Diamond was substituted, with Mr. Frederick Vokes and Miss Victoria Vokes—always entertaining as a matter of course—in the principal parts. ___

The Daily Telegraph (21 November, 1884 - p.3) NOVELTY THEATRE. In recent years it has pleased several lady novelists—mostly amateurs—to write about the stage. Theatrical novels are said to pay, and there is a wholesale supply of inaccuracy and foolishness to meet a somewhat unwholesome and hysterical demand. So long as women who know literally nothing of the stage, and trust wholly to their imagination for their facts, keep true to the circulating library, not much harm is done. The life behind the scenes as depicted by those who have a feverish desire to get there is sufficiently ludicrous; but when the silly theatrical novel is adapted for the stage proper the result is indeed sad. We have not had the privilege of reading “Through the Stage Door,” but we trust that its incidents, its motive, its characterisation, and its object are not nearly so crude and childish as those depicted in “Lottie,” a new and original comedy produced last night. The author of the novel or the play—we know not, and we care not, which—uncertain of his or her power, has gone to Robertson’s “Caste,” for the mere purpose of misunderstanding an author and spoiling an excellent comedy. In these days of unblushing plagiarism, nothing in its way has been more shameless than the way in which Lottie and Carrie Fane—alias Polly and Esther Eccles—spread the humble repast in Stangate or Soho, whilst, when their backs are turned, Hawtree and George d’Alroy—we beg pardon, Captain Forrester and Mr. Jenkins—come in to discuss that eternal and wearisome subject, the virtue or the vice of the professors of the dramatic art. To judge by the listlessness and apathy with which this everlasting thesis was propounded last night by the actors and actresses on the stage, it may be assumed that they are one and all heartily sick of plays which so audaciously misrepresent their calling. It is very fine fun, no doubt, for young lady novelists to imagine how actresses live, what green-rooms are like, how professionals talk, what slang is indulged in by music-hall stars, what scenes occur outside stage doors, and to attach importance to the silly vulgarities of the lower orders of the theatrical profession; but when all these scraps and patches, these pieces and rags are boiled down into a stew that professes to be palateable, actors and public alike are entitled to protest against the folly. The story of “Lottie” is extremely simple. She is Esther Eccles without her heart, art, or intelligence. She is beloved by a middle-aged Colonel Sedgmoor, who takes her from the stage, and installs her the future mistress of his home whilst he is away at the Cape. A straight-laced sister of this grey-haired warrior is jealous of the girl, sets a plot to ruin her, and the injured maiden repairs to the stage she has deserted to support her family and forget her woe. The seeming mystery is cleared up in the green-room of a theatre after a performance of Hamlet! The story in itself is ingenious and sufficient enough, and in any other setting it might have passed muster. But what so common-place a record of breach of promise has to do with actors’ homes in Soho, with green-rooms, stage doors, advertising persons, music-hall professionals, and such-like clap-trap puzzles the uninitiated not a little. To tell the truth, the whole scheme and object of the play is to pander to vulgar and vitiated tastes, and it is astonishing in these days when the stage is in every one’s mouth that those interested in its future should combine to make it so distasteful. Miss Lydia Cowell and Mr. Harry Nicholls have done clever and excellent work in their time. The one is bright and artistic, the other continually quaint. But it was heart-breaking work for Miss Cowell to play Esther Eccles without a story or dialogue to suit her, and the contemptuous look on the face of a painstaking comedian showed how distasteful it was to get character out of the “Great Jinks” and to burlesque what is already an acknowledged extravagance. For the rest there is really little to be said. It was the opportunity not the zeal that they wanted. One and all were placed in a false position, and when in reply to a conventional but wholly unnecessary call for the author Mr. Harry Nicholls positively assured the audience that “he had never heard of him in the whole course of his life” there was an audible sigh of relief. It had been feared that a mistake had been made by one hitherto held in esteem. ___

The Era (22 November, 1884) “LOTTIE” AT THE NOVELTY. Mr Fane . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr HARRY PARKER When at the Novelty Theatre on the evening of Thursday last Mr Harry Nicholls came before the curtain at the end of the piece named above, and informed the tolerably large and apparently well-pleased audience that he would convey their compliments to the author, there was put with surprising unanimity the question, “Who is he?” to which the actor made reply, and said, “Well, I cannot say, as I have never in all my life before heard of the gentleman.” This great unknown we would seriously advise to remain in the obscurity he seemed to prefer on Thursday evening, for his work is anything but creditable to his taste, his judgment, or his skill; and although on its initial representation it made the unthinking laugh, there is no denying the fact that it also made the judicious grieve. And by the judicious we mean those who have the best interests of the stage at heart; those who would not see members of the profession, so to speak, fouling their own nest; and those who think that evil rather than good must come of turning the theatre, as it were, inside out, and of revealing to the public secrets with which they can have no concern. We understand that Lottie is an adaptation of Miss Harriet Jay’s novel called “Through the Stage Door,” but we speak with no authority on this point, not having perused the work, but we shall say very emphatically that in the first place there was no necessity for the author of the so-called comedy to expose what he calls stage life, and, secondly, that if he thought there was, he is to be severely condemned for showing it in its coarsest and most vulgar aspect. One of his dramatis personæ, a representative of the ballet or burlesque, when reminded by her ultra-theatrical mother of her duty to art, is made to reply “Oh, bother art!” and the author of Lottie we can imagine echoing her words and endorsing them with the vulgar comment,” them’s my sentiments.” All through Lottie he seems to us to be saying, “Bother art! Let art take care of itself; let the stage be degraded; let the seamy side of the profession be turned uppermost for the gods to laugh at; what care I, if success, which means money, attend my efforts?” We have said before, and we say again, that such pieces as Lottie, with its stage-door and its green-room, and its actors and actresses making up, and with swells of high and low degree gaining easy admittance, tend to bring about that familiarity which, according to proverbial philosophy, is productive of contempt. Happily, apart from its grossly bad taste and its vulgarity, Lottie is a weak piece, weak in construction, weak in dialogue, and flimsy in the extreme in plot. Such story as there is is very soon told. Colonel Sedgmoor, a regular patron of the drama, has seen upon the stage Lottie Fane, who belongs to a theatrical family, and has fallen in love with her. His intentions are “strictly honourable,” and he visits her in her humble home, is introduced to her homely old father, to her very theatrical mother, to her sister who belongs to burlesque, and to her sister’s “young man,” who is a comic singer. He proposes for her hand, and is accepted, and we see that there is a chance that she will escape the not too honourable attentions of another admirer in the person of Captain Forrester, who is the Colonel’s so-called friend. The marriage would duly take place but for the sudden interference of the military authorities, who order the Colonel’s regiment away to the Cape. Lottie, however, is installed as mistress at Sedgmoor Hall, and is to await the Colonel’s return. Her lot, though, is not a happy one, for she has to submit to the sneers of the Colonel’s sister, who, having kept house for him for years, is determined if possible to retain her position, and to do everything in her power to prevent the alliance of her aristocratic brother with a low-born actress. She, with this object in view, rather encourages the attentions of Captain Forrester to Lottie, and goes so far as to suggest that she should accompany him to London to see her sister in a new part. Finding her effort in this direction fail, she intercepts the Colonel’s letter to Lottie announcing his immediate return, and takes care that she shall hear while she tells to the village parson a lie concerning the Colonel’s altered views, and of his desire to be rid of a discreditable engagement. Lottie’s pride is wounded, and she at once leaves the house with Forrester, and proceeds to town, Miss Sedgmoor receiving her brother, imparting to him the views of his supposed disgrace, and contriving that her story shall be strengthened by Lottie’s opened letter, which she—the sister—has placed upon her dressing-table. The first scene of the third act is the stage-door of the theatre where Carrie Fane is engaged, and to which Lottie has returned, having accepted an offer for the part of Ophelia. Here the Colonel meets Forrester and quarrels with him over what he considers his treachery; here, too, he meets his sister, and casts her off for ever; here the comic singer meets the parson, and takes him behind the scenes to do what he calls his duty, which is to make a clean breast of it and to clear the character of the heroine. Then the curtain having been lowered “for two minutes only,” we are allowed to see the interior of the green-room—where explanations ensue, where mistakes are cleared away, and where Lottie once more allows the amorous Colonel to take her to his arms, and to promise to make her his wife. The amusement of Thursday night’s audience resulted mainly from the clever impersonation given by Mr Harry Nicholls of “the Great Jinks.” Mr Nicholls has evidently made a close study of the manners and customs of the “lion comique” and other “artistes” of the music hall stage, and his little bits of professional slang and his easy and vulgar familiarity with colonels and captains, and parsons and other people supposed to be his superiors, tickled the risibility of all present, and compelled merriment. Mr Harry Parker did his best with the by no means thankful part of the father of Lottie; as did Mr Sutherland with the ridiculously drawn character of Colonel Sedgmoor. Mr. W. H. Day was much too stiff and formal to be altogether satisfactory as the unprincipled Captain Forrester; but Mr Percy Bell, in make up and acting, showed abundant skill as the clerical Dr. Perkins, who in the green-room is made to survey the legs of an actress, and to ask if her costume is not somewhat cold. Miss Fanny Robertson played very cleverly and consistently throughout as the mother, who is a sort of tragedy queen even in her own home, and who cannot talk of onion sauce or other domestic trifles except in the voice of a Lady Macbeth. Miss Dolores Drummond, able actress as she is, could do nothing with so miserable a part as that of Miss Sedgmoor. Miss Leslie Bell took pains to bring out into prominence all the vulgarity of the young lady, who says “bother art;” and Miss Lydia Cowell played with much skill, intelligence, and tact as Lottie, the little bit of pathos and pride combined at the end of the second act assisting to secure her well-deserved honours. We never like to hope for failure, but we shall not hesitate to say that when Lottie disappears, as it shortly must, from the Novelty stage, it will not be followed by our regrets. It belongs to a class which seriously damages instead of serving the interests of the dramatic art. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (23 November, 1884) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. NOVELTY THEATRE. The new comedy, Lottie—understood to have been adapted from Miss Harriet Jay’s story, “Through the Stage Door”—is a disappointing piece of dramatic workmanship; and is, moreover, characterised by singularly bad taste. While assuming to defend the theatrical profession it in reality degrades it, by representing actors and actresses as ignorant, vulgar, and offensive, so that they become objects of ridicule, if not contempt. Stage customs and ways are easily turned to comic account, and when Queen Gertrude is heard discoursing of mutton and onion sauce in the same tones in which she rates Hamlet, laughter naturally ensues. But there is neither art nor cleverness in such work, and we can only condole with the company called upon to carry it out. Miss Lydia Cowell is an actress of known delicacy and refinement, and she displayed some very pretty touches of feeling, though the manner in which Lottie is tempted by a vicious Captain, after being honourably wooed and won by a gallant Colonel, proves fatal to sympathetic interest in her career. The leading comic character is a music-hall singer, “the Great Jinks;” Mr. Harry Nicholls must be credited with giving it striking individuality. Some among the audience, indeed, recognised in it a distinct imitation of a living “artiste;” and the applause was general as well as liberal. None the less, the humour seemed ill-timed, and had an unpleasant flavour. A reverend gentleman, who is taken behind the scenes for the first time, enabled Mr. Percy Bell to introduce a really fine piece of character-acting. Miss Dolores Drummond played a treacherous and designing woman so cleverly as to be hissed, according to the now common custom of greeting the villains of the play. The cast was good all round, Miss Fanny Robertson, Miss Leslie Bell, Mr. Harry Parker, Mr. Sutherland, and Mr. Day acting with earnestness and effect. Mr. Nicholls appeared in response to a call for the author, and said he had never heard his name. Owing to the indisposition of Miss Lydia Thompson, the burlesque announced for Thursday evening was postponed, the closing item being A Rough Diamond, with Mr. Fred Vokes and Miss Victoria Vokes as Joe and Majory. ___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (23 November, 1884) NOVELTY THEATRE. On Thursday night, after a short recess, this house reopened with a play evidently suggested by the late Mr. Robertson’s “Caste,” but which, whilst possessing the same thinness of plot as its prototype, lacks the delicacy of touch and the stage constructive talent which the author of the comedy once so famous at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre possessed. “Lottie” is the name of the new comedy. It is written in three acts and four tableaux, and no name appears upon the bill as to the author of its being. The heroine, whose nom rôle gives the title of the piece, is a young girl, whose habits, tastes, and surroundings are theatrical, and who, together with her parents and sister, make a decent, but by no means luxurious, existence by the stage. Lottie is seen and admired by Colonel Sedgmoor, a man of forty, and his affection is so far returned that she agrees to become his wife. In order to prepare the girl for that state of life in which matrimony will place her, the Colonel removes her from her humble home to his own establishment, over which his sister, a proud and unprincipled woman, presides. During her brother’s absence Miss Sedgmoor so disgusts the girl, that she leaves the house with Captain Forrester, her future husband’s young and handsome friend, and although she does so in all innocence of heart, Miss Sedgmoor contrives that Lottie’s fiancé is led to believe that she has eloped. No sooner, however, do the Colonel and Captain meet, than matters are explained. Lottie is taken back to Colonel Sedgmoor’s arms and heart, and the wicked sister sent away in disgrace. The parts of Colonel Sedgmoor and Captain Forrester were well played by Mr. W. R. Sutherland and Mr. W. H. Day; Miss Dolores Drummond made a capital representative of the vindictive sister, and Miss Lydia Cowell a delightfully fresh and vivacious Lottie. Amongst other characters more or less necessary to the story are Mr. Fane (Mr. Harry Parker), the henpecked husband of Lottie’s maternal parent, Mrs. Fane, who so far transfers her theatrical occupations to the domestic hearth as to order porter with the tragic air of a Mrs. Siddons, and to partake of onion sauce as though she were draining to the dregs “a cup of cold poison,” very amusingly pourtrayed by Miss Fanny Robertson; the Rev. Dr. Perkins (Mr. Percy Bell), who is introduced apparently with a view to ridiculing the managerial farce of clerical certificate-giving to theatrical productions; and Charles Jinks (known as the “great Jinks,” a music-hall singer), given with a vast amount of artistic humour by Mr. Harry Nicholls, who with Miss Cowell shared what honours there were to share of the production. The public have grown weary of stage characterization for the stage, and it would require a far stronger play than “Lottie” to make a permanent success of the materials the author has used. At the end of the last act, however, a call was made for the anonymous one, and on Mr. Nicholls stating that Miss Harris would convey to him the news of the kind reception accorded to his piece, his name was demanded by the applauding ones. Thereupon Mr. Nicholls declared that he had never seen or heard of him. Whether by this was meant that a lady was at the bottom, time will probably reveal. “Gentle Gertrude,” a successful travestie given at a Gaiety matinée in May last, was announced for the conclusion of the evening’s entertainment, but owing to the indisposition of Miss Lydia Thompson, who was to have played the heroine, “The Rough Diamond,” with Miss Victoria Vokes and Mr. Fred Vokes in the two leading parts, was substituted. ___

The Referee (23 November, 1884 - p.3) “Lottie” at the Novelty on Thursday evening attracted a good audience. It is said to be an adaptation of Miss Harriett Jay’s story “Through the Stage Door.” The whisper went round the house that it is the work of Mr. Robert Buchanan, who is very fond of Harriett, with whom just now he is in America. Upon the point of authorship, however, I shall not speak decidedly, for when at the end somebody asked Mr. Harry Nicholls for his name, that funny fellow declared solemnly that he has never heard of him since the day of his nativity. But really it doesn’t matter, for “Lottie” is a very trumpery sort of work which seems to have been suggested by Tom Robertson’s “Caste,” and which is about then thousand miles behind that famous piece in wit and interest and constructive skill. A Colonel Sedgmoor has been to the theatre, and has become smitten with a certain Lottie Fane. He wants to marry her, and he visits her at her own humble home, what time she and pa and ma, and sister Carrie, and sister Carrie’s sweetheart, the Great Jinks, a comic singer, are sitting down to roast shoulder and onion sauce, and fizz without a shadow of fizz in it. He really means business, and says so, and Lottie has visions of future splendour, with flunkeys to wait on her and liveried coachmen to take her and pa for beautiful drives in the park. The Colonel, however, is suddenly put under orders for furrin parts. As he is so much gone on the girl you would think he would get a licence and marry her at once; but he doesn’t. He instals her, though, as mistress of his ancestral home—I believe that is the right term in these cases—and instructs his wicked and elderly ugly sister to coach her up in the ways of the aristocracy. The elderly ugly sister does nothing of the sort. She doesn’t want to lose her comfortable situation, and consequently she allows Lottie to play the tomboy, and to flirt desperately with a certain Captain Forrester, who also has seen her and admired her at the theatre, and who has formed a plan not nearly so honourable as the Colonel’s to secure her. Miss Sedgmoor presently, through the medium of an elderly vicar, contrives to persuade Lottie that the Colonel, who is coming home, has repented of his infatuation, and so Lottie goes off to town with Forrester, and undertakes to play the part of Ophelia—more “Hamlet,” you see— at the theatre where she was formerly engaged. Outside the stage-door the Colonel and his sister and Forrester have rows, and Jinks, the lion comique, who is sticking up to Lottie’s sister, undertakes to introduce the Rev. Dr. Perkins, who has assisted Miss Sedgmoor in her wickedness, behind the scenes, he having felt some prickings of conscience which have determined him to do his duty and to make things right for the heroine. “Ah,” says the comic vocalist, “you’re like the rest of ’em; but come along, you shall have a look. Only sorry there isn’t a ballet on; would have just suited you, and perhaps you won’t mind writing me a testimonial.” It is in the green-room of the theatre that the mistakes are cleared up, and when the curtain falls Lottie is in a fair way to realise her day dreams about carriages, the flunkeys, and the drives in the parks. Plays which give the public a peep behind the scenes are common enough, but I don’t like them, and there can be no doubt they are a mistake. The charm of the stage is stage illusion. Directly you show the playgoer Juliet or Ophelia or Pauline or Desdemona putting on the powder and the paint, and then going home to grab at roast shoulder and onion sauce, with “Give me a bit of fat, please, pa,” the illusion is gone, and worship gives way to something like contempt. The people engaged in “Lottie” worked well enough, and Miss Lydia Cowell strove hard, but strove in vain, to get up something like sympathy for the heroine. Mr. Harry Parker was her pa, but the part was below par, and he could make nothing of it. Mr. Sutherland was very serious as the spoony Colonel, at whom everybody was disposed to laugh notwithstanding the actor’s excellent efforts. Mr. W. H. Day, as the naughty lover, had his best efforts spoilt by the stiffness of his masher collar, and I think it must be said that the only high scorer among the gentlemen was Harry Nicholls, who, as the Great Jinks, was very, very funny, the audience laughing loudly when he expressed surprise because the Rev. Perkins—well played, by the way, by Percy Bell—had never heard of him, and invited him to give him a call at the three ’alls where he did “turns”—the “South,” the “Pav.,” and the “Troc.” Miss Leslie Bell, as Carrie, went the whole animal, and said, “Bother art!” as though she meant it. I must say, though, that she seemed rather nervous about the shapely legs which, in the last act, the parson so much admired. Miss Fanny Robertson was amusing as the mother, who carries her stage work into her own home, and who greets visitors with such speeches as “What doest thou in the country of the Macgregor?” ___

The Daily News (24 November, 1884) Mr. Mortimer asks us to deny the truth of the statement which has been made in some quarters that he is the author of the new comedy entitled “Lottie,” and produced last week at the Novelty Theatre. As a matter of fact, the piece is an adaptation by Mr. Robert Buchanan of Miss Harriett Jay’s novel “Through the Stage-door.” ___

Northern Echo (24 November, 1884) Miss Nellie Harris has scarcely “struck oil” with “Lottie,” the comedy produced at her theatre, the Novelty. The unnamed author of this work has gone to Robertson’s “Caste” for the root idea of the piece; but, like Sir Fretful Plagiary in “The Critic,” he has spoilt it in the taking, and has vulgarised a story which needs very careful handling to make it anything but offensive. “Lottie” was under the disadvantage on the opening night of being played before an auddience disappointed at knowing that Miss Lydia Thompson, owing to indisposition, could not appear; but even if it had been given before the most friendly audience in the world it would not have secured a success. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (24 November, 1884) Mr. Mortimer denies the truth of the statement which has been made in some quarters that he is the author of the new comedy entitled “Lottie,” produced last week at the Novelty Theatre. The piece, it appears, is an adaptation by Mr. Robert Buchanan of Miss Harriett Jay’s novel “Through the Stage-door.” ___

The Stage (28 November, 1884 - p.17) NOVELTY. On Thursday, November 20, 1884, was produced here a new and original comedy, in three acts, entitled:— Lottie. Mr. Fane . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr. Harry Parker. The less that is said of this so-called new and original comedy the better. It appears as a stage play, and yet it tends to be-little the stage that it should surely uphold, and to bring into derision the members of the very calling that it should support. Had it been more adroitly constructed and better written, its success might have been regretted, but as it is very indifferently put together, and as the dialogue is not of the first order of merit, it will speedily, it may be assumed, take its place among the failures of the season, and but few people will regret its departure into silence. The story related is that of an actress who is loved by an elderly gentleman. The pair are betrothed, and the actress spends a visit at the home of her future husband during his absence at the Cape. She is treated with singular rudeness by her prospective sister-in-law, the evil genius of the play, who induces her brother to believe that the girl is unfaithful to him. Thereupon the brother rushes up to town, a reconciliation takes place in the green-room of the theatre, after a performance of Hamlet, and the patient, long-suffering virtue of the actress is rewarded with the hand and heart of her military lover. The actors seemed to feel the feebleness and absurdity of their parts, and were accordingly affected in their acting. Mr. Harry Nicholls had to exaggerate the supposed extravagancies of a good-humoured music-hall “artiste,” and Mr. W. R. Sutherland vainly endeavoured to make the character of the lover sympathetic. Miss Lydia Cowell was bright, intelligent, and charmingly natural as the heroine, and Miss Dolores Drummond was an accomplished representative of the Colonel’s selfish sister. Mr. Harry Parker, Mr. W. H. Day, Miss Fanny Robertson, Miss Leslie Bell, and others in the cast, were seen to but small advantage. Mr. James Mortimer denies the authorship, attributed to him in certain quarters, of this work. As a matter of fact, it has transpired since the production of the piece, that it had been adapted by Mr. Robert Buchanan from Miss Harriet Jay’s novel, “Through the Stage-Door.” In consequence of the indisposition of Miss Lydia Thompson, who was to have appeared on Thursday, Mr. Fred. Vokes and Miss Victoria Vokes filled up the vacancy in the programme, by appearing in a somewhat mutilated version of The Rough Diamond. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (29 November, 1884 - p.10) NOVELTY THEATRE. Lottie, the new comedy with which Miss Nelly Harris has now re-opened the Novelty, is, it seems, a version by Mr. Robert Buchanan of a novel by Miss Harriet Jay called “Through the Stage Door.” If this fact had not been semi-officially announced, we should certainly have concluded that the piece was merely an adaptation or vulgarisation of Robertson’s Caste. Most of those who have discussed this foolish work have pointed out in detail its resemblances, so far as plot and motive are concerned, to its famous prototype. We need not, therefore, describe again how, in Lottie, an honest hard-working little actress engages herself to an aristocratic admirer, how his introduction to her sordid home is effected, and how her relations and friends conduct themselves when they visit her at the country house to which she is promoted. The one amusing character in the piece is the Great Jinks, a music-hall singer to whom the heroine’s sister—a most degenerate Polly Eccles—is engaged. But Jinks’s conduct in the house of Colonel Forrester is simply impossible; and there is hardly a touch of true sympathetic human nature in the whole play. All is conventional and artificial to the last degree, and when the dialogue fails to entertain—which is not seldom—the action certainly does not arouse the faintest interest. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (29 November, 1884) The theme of “Lottie,” the new three-act comedy brought out at the Novelty, was treated so much better by Tom Robertson in “Caste,” that it was questionable policy to produce “Lottie.” The spirited acting of Mr. Harry Nicholls as the “Great Jinks,” of Miss Dolores Drummond as Miss Sedgemore, and of Mr. W. R. Sutherland as the military lover was thrown away; as was the native grace of Miss Lydia Cowell as Lottie, and the vim of Miss Robertson. ___

The Graphic (29 November, 1884) Mr. James Mortimer asks us to say that the statement that he is the author of Lottie, recently produced at the NOVELTY Theatre, is erroneous. The piece referred to is an adaptation by Mr. Robert Buchanan of Miss Harriett Jay’s novel Through the Stage Door. ___

The People (30 November, 1884 - p.6) NOVELTY. “Lottie,” a comedy in three acts, by an author who shows his highest wisdom by electing to remain anonymous, was produced last week at the Novelty. Set forth in the playbill as new and original, the piece, with many pretensions to both, has no just claim to either; it being a moral certainty, from intrinsic evidence flimsily disguised, that has Robertston’s “Caste” and Miss Jay’s “Through the Stage Door” not been written “Lottie” would never have existed. From the novel is taken a story supposed to depict life behind the scenes,. but only serving to prove how ignorant its authoress must be of the professional rules and customs of a green-room. From the play are picked its two heroines, Esther and Polly Eccles, both so vulgarised in the filching—“the wise call it conveying”—as to be scarcely recognisable by their characteristics. Then, among the men, Colonel Sedgmoor stands for D’Alroy, who goes away and comes back like Robertson’s hero—no, not like Robertson’s hero, but in a conventional way as commonplace as his character. D’Alroy’s brother officer and friend, Captain Hawtree, finds his weak and colourless counterpart in Captain Forrester, also the friend and brother officer of Sedgmoor. Where the perverted resemblances to “Caste” leave off those from Miss Jay’s book begin. There is a certain Rev. Dr. Perkins common to both the novel and the play, who, patronising actors, gets smuggled through the stage door, and once “behind” improves the occasion, and, as he imagines, the place, by openly expressing his amazement in the green-room to the actresses he meets there at finding nothing immoral in their conduct or company. Such impertinence in the actual life so falsely depicted would inevitably lead to the speedy ejection of the pharisaic divine and moralist. The trite plot of “Lotto” is fortunately for the present reader told in a few words. Colonel Sedgmoor falls in love with an actress of poor but honest parentage and corresponding abilities. Ordered off to India, he leaves Lottie affianced to him as his future wife at home in charge of his sister at Sedgmoor Hall, where the girl is visited by her very objectionable relatives. Not unnaturally disgusted at the company thus imposed upon her, Miss Sedgmoor, with a view to relieve her family of an alliance with such a depth of social vulgarity, herself stoops to even deeper moral baseness by misrepresenting Lottie to her brother on his sudden return as false to her troth plight. Why so straightforward a man of the world as the colonel, with such insufficient evidence of Lottie’s alleged faithlessness, does not immediately seek his maligned lady love and have it out with her, thereby disproving his sister’s wilful slander by a personal explanation, is incomprehensible. As it is, the meeting is delayed and probability set at naught solely for the purpose of eking out the story, the dénouement of which is robbed of nature by procrastination and of interest by anticipation. As the characters were as devoid of freshness as the plot, there was little scope for originality in the acting, which, without special excellence of individuality was fairly good all round. Miss Fanny Robertson, as the mother of Lottie, and herself an actress, made the most of her opportunities by displaying the humour of a tragedy queen in domestic life. The perfidious Miss Sedgmoor, with whose motives all decent people must sympathize while objecting to her means for their enforcement, was enacted with all the style an d naturalness of which the part was capable by Miss Dolores Drummond. As Lottie Fane, Miss Lydia Cowell, while easy and assured in her acting, failed to indicate that innate refinement which with such domestic surroundings could alone have fascinated the high-bred gentleman Colonel Sedgmoor purports to be and was as acted and embodied by Mr. W. R. Sutherland. As a music hall singer and comique, the brother of Lottie, Mr. Harry Nicholls, played the part so mirthfully as to fully justify the repugnance felt by Miss Sedgmoor at his presence as a guest in her family home. Other characters were played effectively by Messrs. Harry Parker, W. H. Day, Percy Bell, A. Chudleigh, and Miss Leslie Bell. The piece was received with the customary evidences of favour by the audience. The comedy was to have been followed by a burlesque of melodrama new to London, entitled “Gentle Gertrude,” in which, as announced, the title role would have been taken by Miss Lydia Thompson, but, in consequence of the serious illness of that lady the production was deferred, “The Rough Diamond,” with Mr. Fred and Miss Victoria Vokes, being substituted at an hour’s notice. (p.10) “Lottie,” at the Novelty, it appears, after all has been dramatised from Miss Jay’s story, “Through the Stage Door,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan instead of Mr. Mortimer. The explanation, be it understood, is given to the public, not through Mr. Buchanan laying claim to the adaptorship, but by Mr. Mortimer’s repudiation of it. ___

The Theatre (1 December, 1884 - p.306-307) “LOTTIE.” |

|

|

|

Toujours Perdrix! Are we not getting a little tired of the back attic actress and the patronizing swell, the humble rival, the dirty table-cloth, and the eternal smell of onions? It may be all true, but who cares to be so constantly reminded of it? We have heard all about it before in “Caste” with infinitely more tact, and, in Triplet’s lodgings with infinitely more pathos; so why go over the old ground in this crude and unsatisfactory fashion. We know all the puppets by heart before the curtain rises. The father is a seedy and broken down actor, who talks of Kean, the palmy days and the legitimate drama, and who spends his time in copying out manuscripts and smoking strong shag tobacco. The mother struts about as a tragedy queen, and uses stale stage phrases for her every-day parlance, an impossible woman in real life, and only to be tolerated in a wild burlesque. The eldest girl, who is the heroine of romantic drama, is adored by some swell in the stalls, who makes honourable love to her on the sly, and would die rather than hurt a hair of her head; the younger sister is flighty, coarse, and vulgar, who says “Bother art!” and unites herself to a low music-hall singer, who struts about and makes an audience of shop-boys roar when he alludes to “the Pav. and the Met. and the Troc.” Once having got these stupid lay figures or dummies together, the movement begins. The everlasting discussion of stage morality is carried on ad nauseam. The wicked seducer comes to the virtuous home to tempt the romantic heroine from her family circle. The middle-aged “masher,” with grey hair and a faultless collar, enters the abode of bliss, and discovers the united family wallowing in onions and revelling in slang. Society pitches into the stage and the stage into society. A lady of birth and breeding very properly resents the insult of introducing to her presence a low music-hall cad in preposterous costume, and an impertinent minx whose place ought to be the back kitchen, and thereupon the stage-struck novelist attempts to show that society is very harsh and intolerant toward the ill-used and hard-working profession. Society is nothing of the kind. There never was a time when society committed such solecisms for the sake of patronizing and petting the stage. Actors who are educated, and can behave themselves like gentlemen, get into good clubs and are received anywhere. Actresses who insist upon being taken at their own valuation force themselves into society, and are alternately patronized or ignored. As for the rest, if they like onions and pots of porter, and penny cheroots and music-hall slang, let them keep to themselves, and not whine because those of gentle birth and breeding don’t care to associate with such people—very good, no doubt, in their way, but far happier where they are. Master-hands have drawn Costigan and the Fotheringays, Polly and old Eccles, Triplet and his children; but such pictures of the stage as are shown in “Lottie” are tawdry and ill- coloured at the best. That they are absurd goes without saying. The scenes in this play that occur outside the stage-door of a theatre and inside the green-room are palpably absurd to the least informed in such matters. We will take a stronger view still. The man or woman who, not being concerned in the profession of acting, ever ventures behind the scenes of a theatre does so to the dead destruction of all imagination. No one can find real pleasure in ripping up a doll and scattering the sawdust. Illusion, fancy, poetry—all disappear directly the footlights are crossed. If this be true of those who are sometimes compelled to act contrary to their inclination, how much truer it must be of the general public, who are not concerned in the petty and trivial details of an actor’s life. No good or careful acting could save such a play. Miss Lydia Cowell has great intelligence, she enters heart and soul into every character she personates, and she should certainly have permanent employment at one or other of the comedy houses; but she could do very little with the washed-out version of Esther Eccles. Mr. Harry Nicholls was cast for the music-hall comique, and made the part as funny as it was possible to make it; but, on the whole, there are few pleasant recollections in connection with a play that was at once commonplace and vulgar. ___

The New York Times (10 December, 1884) “Lottie,” a drama recently acted in London, is founded on a novel by Miss Harriet Jay called “Through the Stage Door,” and Mr. Robert Buchanan is credited with its authorship. _____

Next: Agnes (1885)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|