|

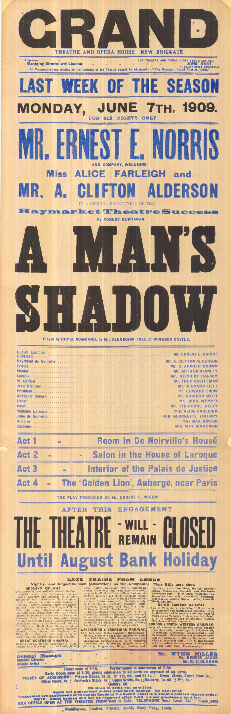

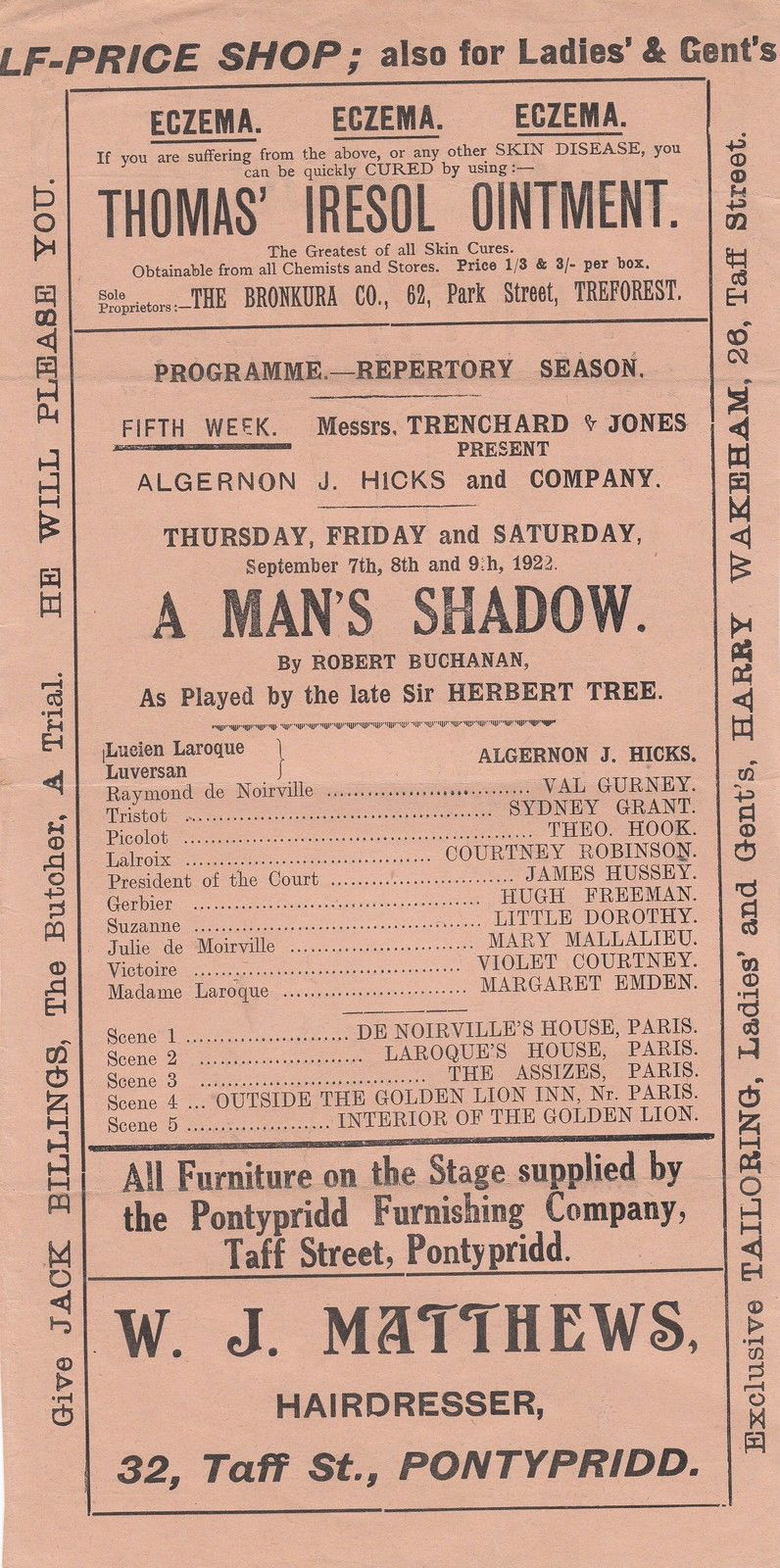

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 26. A Man’s Shadow (1889) - continued ii

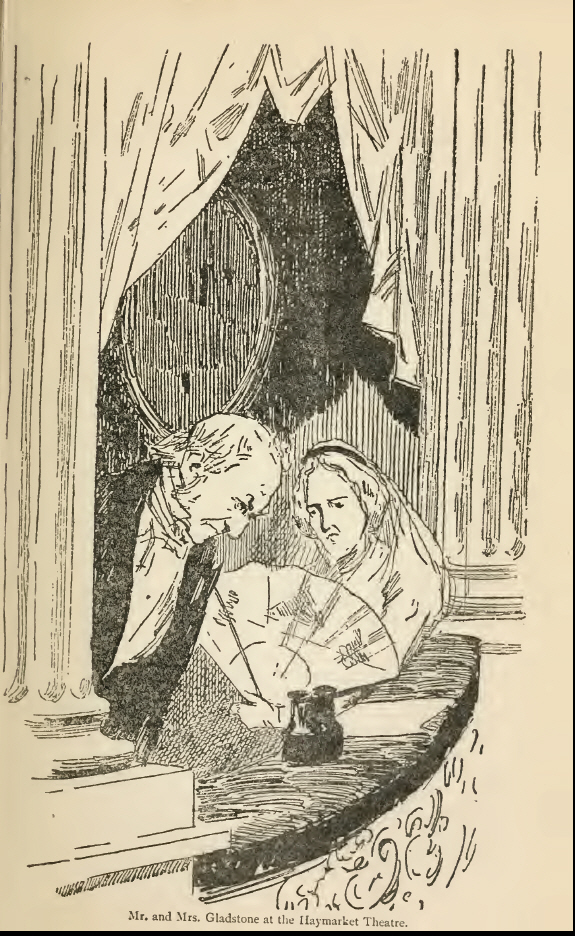

The Era (26 September, 1891 - p.9) THE MARYLEBONE. Henriette ... Mrs HENRY GASCOIGNE It was evident on Saturday evening from the favourable reception given to A Man’s Shadow that Mr Gascoigne’s policy of producing the melodramas and plays that have won popularity in more fashionable centres is one that meets with the entire approval of his patrons. The story that Mr Robert Buchanan has adapted with such skill from the Ambigu piece Roger La Honte is once that appeals with irresistible power to a popular audience. The force of cruel circumstance that overwhelms Laroque and makes him suffer for the crime of Luversan is due to the strong facial resemblance between the two men; and in this respect only A Man’s Shadow resembles Le Courrier de Lyon, known to Lyceum audiences as The Lyons Mail. Mr Buchanan in his slightly compressed version has skilfully retained all the best situations of the original piece; and none of these have created a more powerful effect at the Marylebone during the week than the solemn trial scene, where Raymond De Noirville, under the burden of an imagined dishonour put upon him by the man he is defending, quenches the bitterness of hate that gnaws at his heart, bravely attempts to do his duty as an advocate, and falls dead in the attempt. When A Man’s Shadow was produced at the Haymarket the fine acting of Mr James Fernandez as the advocate produced a very remarkable impression in this same scene—one of the best of its kind that has ever been composed in melodrama. Mr J. Frederick Powell, the Raymond De Noirville of the Marylebone cast, attacked its difficulties bravely and successfully, his savage and whispered upbraiding of Laroque, as well as the working of his facial muscles indicating the intense excitement under which the advocate is labouring. His speech for the defence was powerful in its intensity, and there was no undue forcing of the note. The part is one that some actors might be tempted to “tear a cat” in. Mr Powell avoids the Scylla of rant, without falling into the Charybdis of tameness. An altogether artistic piece of acting, too, was that of Mr Acton Bond, on whose shoulders fell the double responsibilities of the rôles of Laroque and Luversan. The difference in the characters is a remarkable one, though the lineaments are so alike. Mr Bond’s success at the Marylebone is greatest when, as soon as the dignified and manly Laroque has left the dock in the trial scene, his villainous counterpart, with a horrible chuckle, makes his appearance opposite to hand Julie De Noirville’s fatal note to her husband. Could it be one and the same individual playing the two parts? was a question that naturally arose in one’s mind, and this very doubt is perhaps the greatest tribute that can be paid to the young actor, whose elocution is so excellent, and whose power is already so well under restraint. Mrs Henry Gascoigne made an excellent Henriette, delineating with no little skill the conflicting emotions of the distraught wife, and Miss Madge Denzil’s Julie was a careful and painstaking performance. Miss Lucy Murray as Victoire, the waiting-maid, also did well. The puerile humour of Picolot and Tristot does not add strength to the trial scene, but it seemed to be relished by the Maryleboners, who roared at the “business” of Mr Wilford Bailey and Mr Charles R. Stone. Mr T. S. Deller had a comic appearance as Jean Ricardot; Mr Charles Morgan was a good Lacroix; and Mr John Henderson’s president could scarcely have been improved upon. Miss Lily Ivanhoe’s pronunciation as little Susanne left something to be desired. Other parts were adequately played by Messrs Edward Boddy, Arthur Hart, Williams, J. Vivian, and G. Francis. The Waterman preceded the principal piece of the evening. Mr John F. Storer, the courteous acting-manager of the house, carries out his duties with real tact. ___

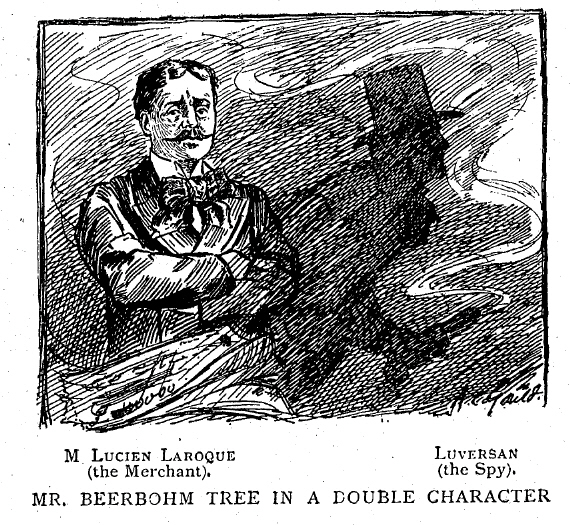

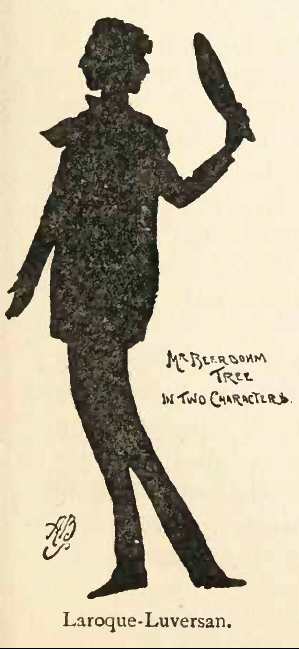

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (6 September, 1892 - p.5) THEATRE ROYAL. The annual visit of Mr. Beerbohm Tree and his Haymarket Company to Manchester is always regarded as one of the events of the theatrical year. It is looked forward to with interest, and leaves pleasant memories behind it. The public of this city is not slow to recognise and appreciate histrionic merit, and so deep has been the impression left on the local theatrical mind by Mr. Tree’s previous visits that it was only reasonable to expect a full and enthusiastic house to welcome his return at the Theatre Royal yesterday evening. During the present visit of the company several plays that have won for themselves a niche in the temple of Thespis will be presented, the brief season opening last night with “A Man’s Shadow,” a drama adapted from the French play, “Roger la Honte,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan. We have often had to express our obligations to French sources for cleverly constructed plays. This is another of them. It reminds us, in one particular, at least, of “The Lyons Mail,” in that it affords Mr. Tree, as Mr. Henry Irving, in “The Lyons Mail,” an opportunity of appearing in a double role. The central figure is that of “Lucian Laroque,” a Parisian merchant in financial distress, who is being relentlessly pursued and wrongfully involved in a murder charge by his alter ego, Luversan, a spy. These are the characters assumed by Mr. Tree. Of course it is easy for one man to look like two men so much alike that nobody in a sense can tell the difference, but it is not so easy to present two wholly opposite characters, and the audience last night could never have been in doubt for a moment that Laroque and Luversan were one and the same. If Mr. Tree could completely change his intonation, it would be a fine performance, but even then there is a physical difficulty which Mr. Tree does not thoroughly overcome. Two men may be alike, but then all the world knows they are very different, and we expect to be made aware of that difference in a play. This dual character is not suited to Mr. Tree. He is not a good villain of the character of Luversan, but as Laroque, the much sinned against merchant, he is very powerful indeed. The trial scene was deeply impressive. Here, Miss Barton, as Susanne, the daughter of Laroque, when giving her evidence, brought tears into the eyes of many who would fain not acknowledge such a weakness in such a place, and there is very little humour in the small parts of Picolet and Tristol to counterbalance the overwhelming heaviness and solemnity, even tragical ending of the trial, the prisoner’s counsel, Raymond de Noirville (Mr. Fred Terry), falling dead in front of the dock as he is about to reveal his own wife’s supposed dishonour to save Laroque’s life. The part of Henriette Laroque, wife of the hero, was extremely well rendered by Miss Norreys, whose performance, in conjunction with that of her daughter in the murder scene, was powerful and realistic to a degree seldom witnessed. Miss Lily Hanbury, too, deserves commendation as Julie de Noirville, whose guilty love for Laroque forms the basis of the plot. The company, all round, is a capable one, and their efforts reaped very sincere applause, the principals being repeatedly recalled. A word of praise should also be given to the stage manager. The piece was excellently staged. ___

The Stage (28 September, 1893 - p.12) THE BRITANNIA. A powerful and impressive presentment of Robert Buchanan’s adaptation from the French, A Man’s Shadow. is the fixture for this week, and until further notice, at the great Hoxton theatre. This performance is as good as any we have seen on the Britannia boards. It goes without saying that the staging is excellent, and the acting is in all respects worthy of the reputation which the company here have won. There are many points in this play which appeal to lovers of strong dramatic effect. Mr. Algernon Syms is in his very best vein in the double rôle of Lucien Laroque and Luversan. His work in the second act is quite masterly, and deserves to be ranked among his best efforts. The intense naturalness of it, the repressed emotion, the well portrayed despair of the man who finds himself falsely accused of the most terrible of crimes, and the distinctly limned personality of the shadow, Luversan, are strong points on which Mr. Syms may well pride himself. Mr. Walter Steadman shows what true dramatic fibre is in him in the trial scene of the third act, in which Raymond de Noirville figures so prominently. Mr. Steadman acts brilliantly in this critical scene. It is a splendid effort, and one of the finest things Mr. Steadman has given us. Mr. W. S. Parkes is an effective M. Gerbier. Mr. W. H. Perrette is distinctly successful as Picolet. Mr. Joseph Rowland does well as Tristot. Mr. G. B. Bigwood causes much amusement by his droll portrayal of Jean Ricordot. As President of the Court Mr. Bruce Lindley displays his usual natural style, and has a good make. Mr. F. Beaumont is an effective Advocate-general. Mr. Walter Copley’s brisk and telling manner is well in accord with the part of Lacroix, the police agent. As Henriette, the wife of Laroque, Miss Oliph Webb puts forth all her best powers of tenderness, pathos, and realistic portraiture. Miss Winnie Whyte, who has been specially engaged for these performances, is remarkably effective as Suzanne. There is real talent in the acting of this clever child. Much of her good work is doubtless due to careful training, but there are, too, lights and shades of facial expression and inflections of tone which cannot be other than spontaneous and natural. Miss Lalor Shiel is as vivacious and attractive as ever as Victorie. Miss Beatrice Toy is a charming Julie. The remaining parts are in good hands. The varieties are entrusted to Harry Lemore and Adeline, the latter of whom goes through her clever trapeze performance. The afterpiece is My Turn Next. ___

The Stage (10 June, 1897 - p.12) THE MATINEE. Messrs. Acton Bond and Charles Meyrick, who are starting on tour with their company in A Man’s Shadow, are filling a week’s engagement at the comfortable theatre in Langham Place, where the performance of Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of Jules Mary and Georges Grisier’s popular melodrama, Roger La Honte, was received with great cordiality on the evening of Whit Monday. Many things have happened in Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s progress since September, 1889, when he was seen at the Haymarket in the characters of Lucien Laroque, the honest man and brave soldier, who is the victim of circumstantial evidence, and the so-called “Shadow,” Luversan, spy, blackmailer, and murderer. Though not so fine a dual rôle as that of Lesurques and Dubose in The Lyons Mail, the Laroque-Luversan combination offers excellent opportunities to an actor of versatility and resource, and of these chances Mr. Acton Bond made generally good use in the representation given at the Matinee on Monday. perhaps he did the better work as Luversan, making that jaunty rascal blithe and debonnair even in his desperation, and reproducing frequently the characteristic tones of Mr. Tree. Besides managing the changes adroitly, Mr. Bond differentiated admirably between the physical and psychological traits of the two men, and his demeanour as the wrongly-condemned Laroque was refined, gentle, and earnest, the beseeching of the child Suzanne to speak the truth in the Trial scene, and the grave reproach to the still suspecting wife in the last act, being among the other noticeable points in an excellent and highly creditable performance. Provincial playgoers who appreciate artistic acting should enjoy Mr. Acton Bond’s twin assumptions of Laroque and Luversan. The company supporting him in this in parts powerful, but, speaking generally, artificial, melodrama, are on the whole efficient, and some of the characters were very well played, although in the inept and dramatically worthless “comic relief” supplied by Mr. Buchanan, Messrs. H. G. Payne, W. Devereux, and Robson Paige were unable to do very much as the little Corporal Tristrot; the big Sergeant Picolot, and the egregious expert in handwriting, Jean Ricordot. It is a wonder, indeed, how such feeble comedy ever passed muster. In the part of Raymond de Noirville, which at the Haymarket Mr. Fernandez played with such tremendous effect, Mr. Frederick J. Powell gave on Monday a performance studiously restrained up to the scene where the advocate works himself into a frenzy and falls dead of heart disease in the Assize Chamber as he is on the point of confessing his wife’s shame to save his comrade’s life. Herein Mr. Powell acted with considerable [Note: there seems to be a missing line here.] juncture was followed, as before at the Haymarket, with warm applause. Julie de Noirville and Henriette Laroque appear respectively in two only out of the four acts, and hence the characters are less important than they should be in a more skilfully contrived dramatic scheme. Miss Dora de Winton, however, as Julie showed with emotional intensity and deep-toned voice the fluctuations between passion and revengefulness experienced by Laroque’s ci-devant mistress, and Miss Keith Wakeman, although almost too subdued in the matter of utterance, brought out well the affection and perturbation of the soul-harrowed wife. As the little girl Suzanne, who refuses at the trial to inculpate her father, Miss Lulu Valli spoke and acted with the true ring of childish sorrow, and indeed at all points her performance was one of high promise. Miss Edith O. Crawford did capital work as that unwilling witness Victoire, the waiting maid; and Mr. Reginald Rivington as the police agent Lacroix, and Mr. John Henderson (who also stage managed a carefully- executed “production”) as the President of the Court, were both of much service. The other parts were passably filled, and the effects were suitably made. Mr. Charles Meyrick is business manager of the company. ___

The London Musical Courier (17 June, 1897) Never were the theatres more interesting than now. There are good things coming and going everywhere. The scribe who would see them all should have, like Argus, a hundred eyes, of which only two go to sleep at one time. This week those who could not get to the Grand Theatre, Islington, have missed Mr. Forbes Robertson in Pinero’s splendid sermon, “The Profligate.” ___

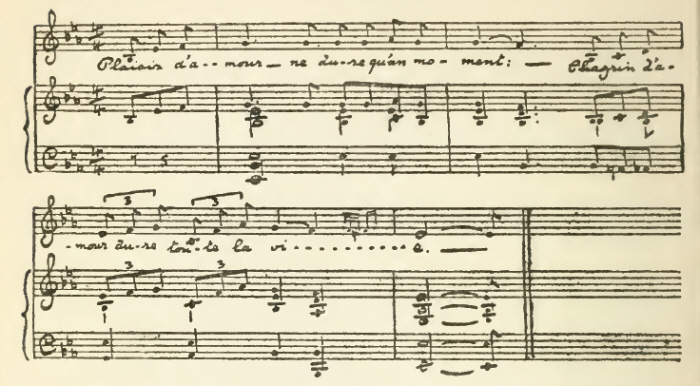

The Era (3 July, 1897 - p.9) THEATRE METROPOLE. Lucien Laroque ... This week Camberwellians are enjoying the great Haymarket Theatre success, A Man’s Shadow, and the soul-stirring drama is meeting with enormous success at Mr Mulholland’s popular theatre. The company engaged by Mr Acton Bond and Mr Charles Meyrick is a particularly talented one, and each member deserves the highest eulogy. Mr Acton Bond appears in the dual rôle of Lucien Laroque (the man) and Luversan (his shadow), and is to be complimented upon his rendering of a very difficult and exacting double rôle. His polished performance is much appreciated, his distinct contrast between the real man and the shadow or “double” being decidedly clever. Another most finished piece of acting is supplied by gifted Mr Frederick J. Powell in his portrayal of Raymond De Noirville, whose speech in the defence of Laroque is most impressively made. Mr. Gerbier is intelligently played by Mr Charles Seymour. Picolot, a sergeant in the French army, and his colleague, Tristot, a corporal, afford Mr Richard Saker and Mr H. G. Payne opportunities to score in the comedy line, which they both do. Mr Robson Paige is very good as Jean Ricordot. Mr John Henderson is dignified and acts with judgment as the President of the Court, and his ability as a stage-manager is conspicuous. Mr Reginald Rivington does well in his interpretation of the police agent Lacroix. As the valet Mr H. Harvey speaks his lines creditably. Henriette is made a real personage by Miss Keith Wakeman, who infuses much vigour into the part, and acts with force and skill. Suzanne, the child, is played most naturally by a well-trained and exceptionally clever and interesting little maiden, Miss Lulu Valli, her actions, facial expression, and speech being well nigh perfect. Victoire is pleasingly represented by Miss Edith O. Crawford, and Miss Dora De Winton looks charmingly graceful as Julie, the wife of De Noirville, her grasp of this heavy part being artistic and worthy of the highest praise. A noteworthy feature is the music specially composed for Messrs Bond and Meyrick’s production by Miss Ella Overbeck. The scenery and mounting are praiseworthy. The play has been rehearsed under the personal direction of Mr Acton Bond, the general management being looked after by Mr Meyrick, assisted by Mr Adnam Sprange. ___

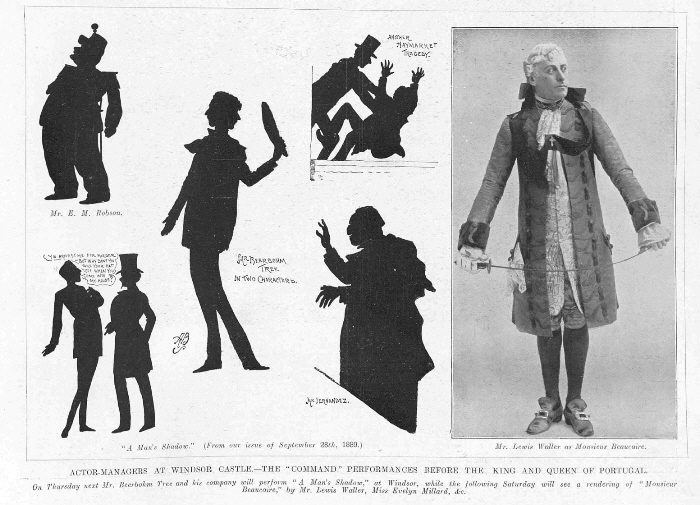

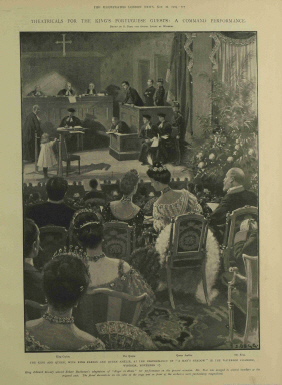

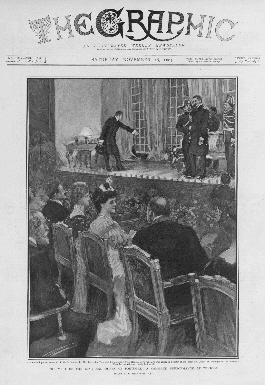

The People (28 November, 1897 - p.9) HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE No surer proof can be given of the ability of a theatrical manager in gauging the tastes and requirements of the play-going public than this revival from time to time of the pieces originally brought out by him. Such reproductions of plays are obviously evidences of their previous powers to attract and entertain. It is accordingly an indirect, and therefore a genuine commendation of Mr. Tree as actor, as well as stage producer, that he has come to be known among frequenters of the theatre as par excellence manager of revivals. His productions, one after another, fill up the programme, as “The Ballad Monger” bears witness for the second and even the third time of asking. The latest exemplification of these revivals was seen last night in the resuscitation of the exciting and interesting drama adapted by M. Robert Buchanan from the French, under the title of “A Man’s Shadow,” first seen at the Haymarket 8 years ago. The shadow in this instance is used in a figurative sense to indicate the darkness of evil in one man contrasted against the brightness of good in another, the two individuals being as in the analogous case of “The Lyons Mail,” as strangely alike in form and feature as they are dissimilar in nature and conduct. Playgoers will recall how they were held by the memorable trial scene in which the loving wife and child are constrained by what seems to them the evidence of their senses to bear witness against husband and father for the murder they were horrified to see committed, seemingly by himself, but in reality by his “shadow” in the person of his nefarious double. The absorbing interest and intense excitement of this scene in the French Criminal Courts repeated itself on the repetition of the incident—after a long interval, last night. Mr. Tree, in his admirably artistic differentiation of the upright merchant and the debauched, dissolute assassin, again gave expression to that protean power of sinking his own identity in his personations, in which Sir Henry Irving alone (in this instance already referred to in “The Lyons Mail”) can be cited as his equal upon the English stage. The emotion of the loving wife and mother, appalled and dazed by her husband’s seeming guilt, was again realised with illusive intensity by Mrs. Tree; and the important part of the counsel for the defence on the falsely charged merchant’s trial, originally acted with such impressive earnestness by Mr. Fernandez, received equally powerful interpretation from its new exponent, Mr. Lewis Waller. At the trial, where the advocate is compelled by a desire to professional duty to conduct his case as to involve the exposure of his own wife’s dishonour, the audience was wrought to a high state of nervous tension by the advocate, under the strain of his terrible mental contenti[] falling dead from heart disease in[], he was uttering the name which would have revealed the secret. Mr. Lionel Brough and Mr. E. M. Robson again impersonated the witnesses, who throw glints of natural humour over the direful procedure of the trial. And Miss Lily Hanbury proved a worthy successor of Miss Julia Neilson in the part of the advocate’s wife. Needless to say that the gratification of the audience at the illusive spell of interest laid upon them by the powerful story with its happy denouement, found expression in the enthusiastic recalls and plaudits at the close of the play. ___

The Morning Post (29 November, 1897 - p.6) HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE. A large and brilliant audience filled Her Majesty’s Theatre on Saturday night, and greeted with enthusiasm Mr. Tree’s revival of “A Man’s Shadow.” It is more than eight years since Mr. Robert Buchanan’s version of “Roger la Honte” was produced at the Haymarket Theatre, and of the original cast only Mr. and Mrs. Tree and Mr. Robson remain. But the play loses nothing by the new interpreters, and the performance was effective in the extreme, the actors being called at least half a dozen times after the third act, and again repeatedly at the final fall of the curtain. “A Man’s Shadow” is pre-eminently a play of effect. The author, doubtful of his power to conjure up visions of the sublime and the beautiful by holding the mirror up strictly to Nature, has preferred to excite our feelings by what is strange and harrowing at the expense of truth rather than run the risk of merely reproducing the commonplace by a too rigid fidelity to human life and character; he has written a melodrama. Everything is sacrificed to effect, but, thanks to the exceeding ingenuity and technical skill of the playwright, the desired result is attained. Printed and read, the story would not rouse our interest and sympathy as the acted play does. This is because in reading we pause and think. In the theatre the events follow one another so rapidly that there is no time for reflection. The plot is founded on a case of mistaken identity. Lucien Laroque, an honest merchant, and Luversan, a spy, are so alike that they are constantly taken for one another. The spy commits a robbery and a murder, and the honest man is arrested, tried, and condemned. He escapes from prison, and in the last act he is confronted with the villain, who shoots himself; the hero’s innocence is established, and the drama has a happy ending. There are three powerful situations. The murder, which takes place in a house seen across the street from Laroque’s room, is witnessed by his wife, his little daughter, and his maidservant. They are convinced of his guilt; but the mother, in an agony of fear, makes her child promise that she will reveal nothing whatever of what has occurred. Suzanne has seen nothing—heard nothing. The intelligent little creature is steadfast to her word; no inducement can move her to incriminate her father—not even his own entreaties to her to speak the truth before the full Court of Assize. There were few dry eyes when the pretty child, overcome by the solemnity of the scene, was carried fainting out of the Court. The merchant’s advocate is his great friend De Noirville, who has married Julie, formerly Laroque’s mistress. But of this De Noirville is ignorant, and for no consideration in the world will Laroque disclose a secret that would ruin his friend’s happiness. And yet it is a question of life and death, for the circumstances are such that on this admission lies Laroque’s only chance of proving his innocence. He prefers the claims of friendship to those of his own honour and his own life. But the most powerful situation of all is that in which the barrister finds himself. Suddenly, in the middle of the trial, he learns the truth. He is placed in the terrible dilemma of neglecting his duty and abandoning the friend whom he loves and whose guiltlessness he can prove, or else proclaim to all the world the worthlessness of his wife. He decides to sacrifice his own peace. But he was grievously wounded in the late war, and before he can conclude the impassioned speech which is to make all clear he falls dead in the Court. It is necessary, in order to bring about these situations and make them sufficiently plausible, to introduce a large number of motives and circumstances, such as the relations between the spy and Laroque’s wife and Julie, the merchant’s financial distress, the giving of money by Julie to a M. Gerbier (the murdered man) to whom Laroque was in debt, the finding of a pistol at the opportune moment, a compromising letter, and many other essential facts. Herein lies the weakness of the play, for these circumstances and coincidences are so numerous and so complex that we labour under the impression that they have been carefully and artificially produced to bring about the catastrophe. The story lacks simplicity and spontaneity. It also lacks the requisite of tragedy—the development of character. The personages are what the author requires for certain actions. They are fixed quantities, and their characters are not re-acted on by the events. Nothing could be finer than Mr. Tree’s rendering of both the merchant and the spy. The men are alike only in face and size; otherwise they are differentiated by innumerable little traits, which show the perfection of the actor’s art. Each has a characteristic gait, a different expression, even the involuntary movements of their muscles, especially of the hands, betray idiosyncrasies. As Laroque Mr. Tree is especially remarkable in the trial scene, a performance on which it would be difficult to improve. Our young stage aspirants would do well to master it in all its details—a task impossible at a single visit to the theatre, where a thousand things claim our attention. But night after night the students should be at their post observing and taking notes. From Mr. Lewis Waller, too, they would learn much. It would be hazardous after this lapse of time to compare his performance with that of Mr. Fernandez as the advocate. But the effect produced by the great speech at the trial, where, torn by conflicting emotions, the faithful friend falls dead before he can incriminate the wife he loves, was in both cases the same—it brought down the house. Mr. Waller enjoyed a well-deserved triumph. The minor parts were likewise excellently rendered, and to Messrs. E. M. Robson, Lionel Brough, and Gerald du Maurier the greatest credit is due for the humorous scenes, which, naturally and appropriately introduced, afford welcome relief from the strain and gloom of melodrama. The actresses had fewer opportunities of distinction. Mrs. Tree was graceful and sympathetic as Laroque’s unhappy wife, and little Miss Dorrie Harris, as Suzanne, was the sweetest, most innocent, and natural little heroine imaginable. It would be hypercritical to find fault because she was dressed as a pretty English girl; for had she appeared more correctly in the usual garb of a French child much of the charm of the picture would have been absent. Miss Lily Hanbury’s talents and devotion to her art have won for her much regard, and she is too true an artist to feel hurt if it is pointed out that to reach perfection it is necessary to conceal that art as much as possible. She has mastered the methods of the stage, but they appear somewhat too obvious in all she does. Let her watch the women of her acquaintance, especially in their emotional moods. She will notice that they rarely speak and move as she does on the stage. The inflection of their voices, the rise and fall of their sentences, is more varied, more abrupt—in a word, more natural. When by chance this is not the case we say: This woman is an actress. It is exactly the converse that we wish to feel of the actress. She does not seem to be acting at all; she behaves as any woman would behave in the circumstances. This is the effect produced on us by Eleonora Duse. And it does not imply that all that is natural ought to be reproduced at the footlights. On the contrary, what takes place there should be altogether art. But the test of its real existence is that it should be mistaken for nature. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (29 November, 1897 - p.5) Whoever delights in strong, thrilling melodrama will be grateful to Mr. Beerbohm Tree for the revival of “A Man’s Shadow.” The story of the unhappy merchant who bears the shame, and narrowly escapes the punishment for, crimes committed by his double, has been retold by Mr. Robert Buchanan with a simplicity, a directness, and a force that inspires the imagination, and takes firm hold on the emotions. The scene is the assize court, where Laroque, the merchant, is tried for murder, may outrage our insular prejudices in favour of judicial decorum, but of its dramatic intensity there can be no question. The examination of the child who believes her father to be a murderer, the discovery made by the advocate that the prisoner—for whose life he was pleading as for his dearest friend—was the lover of his wife, the swift and awful death, with the confession of his own dishonour on his lips—all these are incidents to which the art of the dramatist and of the actor has given palpitating energy and actuality. These qualities are discernible in every part of the performance at Her Majesty’s Theatre. Mr. Tree plays the villain and the victim with nice discrimination, ingeniously emphasising those fine shades of difference which even wife and daughter fail to perceive. Mr. Lewis Waller discharges with ready ability the difficult duties of the advocate whose heart is torn asunder by the conflict between duty and friendship and honour. Mrs. Tree as the distressed wife, and Miss Lily Hanbury as the quondam mistress of Laroque and the wife of the advocate, make up an excellent company. A word may also be said in praise of little Miss Dorrie Harris, whose presentation of childish agony is admirable, though harrowing to the soul. ___

From Dramatic Opinions and Essays - Volume Two by George Bernard Shaw (New York: Brentano’s, 1906 - p. 380-382) A Man's Shadow. Adapted from the French play “Roger la Honte” by Robert Buchanan. Revival. It is not in human nature to regard Her Majesty’s Theatre as the proper place for such a police-court drama as “A Man’s Shadow.” Still, it is not a bad bit of work of its kind; and it would be a good deal better if it were played as it ought to be with two actors instead of one in the parts of Lucien Laroque and Luversan. Of course Mr. Tree, following the precedent of “The Lyons Mail,” doubles the twain. Equally of course, this expedient completely destroys the illusion, which requires that two different men should resemble one another so strongly as to be practically indistinguishable except on tolerably close scrutiny; whilst Mr. Tree’s reputation as a master of the art of disguising himself requires that he shall astonish the audience by the extravagant dissimilarity of the two figures he alternately presents. No human being could, under any conceivable circumstances, mistake his Laroque for his Luversan; and I have no doubt that Mr. Tree will take this as the highest compliment I could possibly pay him for this class of work. Nevertheless, I have no hesitation in saying that if the real difficulty—one compared to which mere disguise is child’s play—were faced and vanquished, the interest of the play would be trebled. That difficulty, I need hardly explain, is the presentation to the spectators of a single figure which shall yet be known to them as the work of two distinct actors. As it is, instead of two men in one, we have one man in two, which makes the play incredible as well as impossible. ___

The Westminster Budget (3 December, 1897 - p.11) REVIVAL OF “A MAN’S SHADOW.” Mr. Beerbohm Tree has promised a revival of “Julius Cæsar,” one of the noblest and most neglected of Shakespeare’s tragedies, and consequently even those of us who affect a lofty standard may well forgive a revival of “A Man’s Shadow,” unless, indeed, the piece which thrilled the audience and was received with very great favour should defer too long the production of the Shakespearean play. |

|

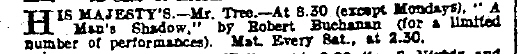

[Advert for A Man’s Shadow from the Daily Mail (6 April, 1905 - p.4).] |

|

|

|

The Graphic (24 July, 1926 - p.27) WITH a night to spare—a rare experience—I went last week to the Elephant and Castle, where the stock company, captained by Mr. N. Carter Slaughter, recently celebrated its 550th performance with a monster bill such as our grandfathers were familiar with. The company has revived from first to last nearly seventy “drawmas,” of which, I fancy, very few have been nearly so good as “A Man’s Shadow”—the one I saw. This was the play in which Tree made a big success in 1889, and which he frequently revived. IT is constructed with great adroitness, but I was rather astonished to hear from Mr. Sidney Barnard, the owner of the Elephant and Castle, that the public in that part of the world does not like plays where there is a double (such as Laroque and Luversan) who look so much like each other. This apparently puzzles the audience, whereas, to myself, that type of thing is one of the excuses for seeing melodrama at all. I can, however, understand that the Elephant and Castle audience, even in a generation of education, should be a little puzzled at the references to Damon and Pythias, with which Robert Buchanan sprinkled the French text on which he worked. ___

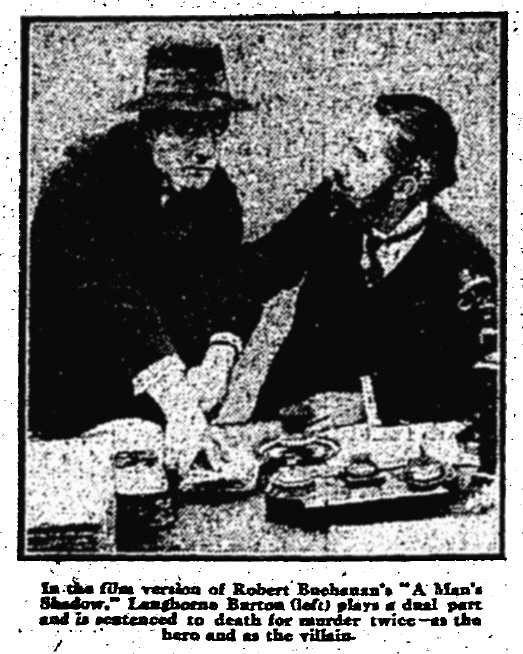

The American production of Roger la Honte; or, A Man’s Shadow _____

Next: Theodora (1889) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|