|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 10. Storm-Beaten (1883) - continued

The Penny Illustrated Paper (24 March, 1883 - p.7) In melodrama, “The Silver King” maintains its pre-eminence at the Princess’s, and will very shortly—as Mr. Wilson Barrett announced on the one-hundredth night—be played to about 25,000 persons every evening in different parts of the globe. Mr. Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, and playwright, has made a strong bid in the same direction at the Adelphi, where “Storm-Beaten” has been produced under the earnest direction of Mr. Charles Warner, who throws his whole soul into the portrayal of the rôle of the hero whose mission it is to brave the Arctic seas to wreak vengeance on the seducer of his sister. Mr. Warner is particularly fortunate to be supported in “Storm-Beaten” by a trio of such true, womanly actresses as Mrs. Billington, Miss Amy Roselle, and Miss Eweretta Lawrence, the last-named young lady being a charmingly natural addition to the ranks of ingénues. The acting, indeed, of Miss Roselle and Miss Lawrence in the best acts of the piece, the first three, would be difficult to excel. So winsome and womanly are their scenes that one infinitely prefers them to the sensation tableaux, which are suggestive, very, of the old Adelphi drama of “The Sea of Ice.” ___

The Graphic (24 March, 1883) THEATRES. ON the basis of his novel, “God and the Man,” Mr. Robert Buchanan has written, for the ADELPHI Theatre, a new melodrama which, both by its length—it is in six acts, counting the prologue as one—and by the extraordinary abundance of its sensational scenes, will remind old frequenters of this house of its most prosperous days, when Mr. Buckstone, Madame Celeste, Mr. O. Smith, Mr. Wright, and Mr. Paul Bedford were its leading stars. Scene after scene of excitement is provided as the story of the cruel wrongs inflicted on the Christianson family by the son of their harsh landlord, Squire Orchardson, and the terrible plans of vengeance conceived by Christian Chistianson, are unfolded; and the talent of Mr. Beverley and the scenic machinists and carpenters have been put into requisition to produce some remarkably picturesque effects. Among these the collision of the ship with the iceberg and the sudden collapse of the icefloe—a well-remembered incident of an old Adelphi drama here skilfully revived—stand forth conspicuously. Besides these there are fine landscape scenes, which were deservedly applauded. Amidst all these brilliant, pictorial, and alarming details, the story, it must be confessed, is somewhat overshadowed; not that due space is denied to it, for it is in parts somewhat tediously elaborated, but rather because, in the pursuit of sensation, its finer elements have in great part disappeared. In the drama, at least, the characters are painted in the strong coarse colours which belong to suburban melodrama. Mr. Buchanan’s villain is so thorough-paced a scoundrel that, not content with ruining the peace and reputation of the unhappy farmer’s daughter, Kate Christianson, he shoots her brother’s splendid dog before his master’s eyes in sheer wantonness.After this, aboard ship he endeavours to burn his antagonist alive. Yet, because he has suffered privations on a desert rock which have softened his victim’s heart, Mr. Buchanan expects his audience to rejoice when this quintessence of villainy returns to claim the love, and, what is more surprising, to find himself the joyfully-accepted suitor, of the woman whom he has selfishly ruined and heartlessly abandoned. Deprived, as it is, of much of the moral beauty with which the leading incidents are invested in the novel, we fear it must be confessed that the story of Storm-Beaten does not lay hold very strongly of the spectator’s sympathies, though the performance has the advantage of the services of that tender, emotional actress, Miss Amy Roselle, in the part of the heroine; and of Mr. Charles Warner in that of Christian, which he plays with abundance of romantic spirit and picturesqueness. Among the numerous other characters which stand out in the performance are Richard Orchardson, played by Mr. Barnes with a frank acceptance of its repulsive features, which is at least creditable to him as an artist; and Dame Christianson, played by Mrs. Billington with a stern sincerity which is highly effective. Miss Eweretta Lawrence, who appears as Priscilla Sefton, is a novice; but she seems likely to develop into something more than a merely pleasing actress when she has acquired the art of sincere utterance. Some other minor parts are well played by Mr. Beerbohm Tree, Mr. Proctor, Mr. Edgar, Mr. Shore, Mr. Redwood, and Miss Clara Jecks; but, unfortunately, these do not much help the story. Mr. Buchanan has, indeed, an unskilful habit of elaborating mere incidental and illustrative matter by way of finding employment for personages who are but slightly connected with the plot. The play, however, was well received; and the author missed none of the honours which attend upon practical success upon the stage. ___

The Athenæum (24 March, 1883) DRAMA THE WEEK. ADELPHI.—‘Storm-beaten,’ a Drama in a Prologue and ‘STORM-BEATEN,’ a drama adapted by Mr. Robert Buchanan from his novel of ‘God and the Man’ and produced at the Adelphi Theatre, is a popular success. Its early scenes are strong and well conceived, and one or two situations to which it gives rise create a powerful impression. If the whole comes short of greatness and the termination is less stimulating than what has gone before, the vulgarization the story has experienced in the attempt to fit it to public tastes must be held accountable. From the drawbacks which attend most stories converted into drama ‘Storm-beaten’ is not free. Compared with the characters of the novel, the secret motives of which are laid bare, those of the play seem thin and meaningless, the change which comes over the hero when he relents in his purpose of murder is but half comprehensible, and the humanizing influence exercised upon him by close commune with Nature in her sternest mood is no longer apparent. This process of deterioration is not confined to the hero. Priscilla Sefton loses the demureness which in the novel is her chief charm, and her scenes of coquetry with Christian Christianson become conventional and commonplace. These and other kindred difficulties might have been combated had Mr. Buchanan preserved in the drama the termination, now sacrificed to vulgar requirements, which his conscience told him was fitting. Some gain in popularity may accrue from the happy end with which the plot is supplied. Artistically and psychologically, however, the story is weakened by the change. A feud such as Mr. Buchanan has shown between Christianson and Orchardson does not end without some sacrifice to the Eumenides. When the two men—pursuer and pursued—come back hand in hand, sworn friends and brethren, to commence in England commonplace lives, the laws of nature and of fate seem turned into ridicule. Two stanzas of the explanatory poem prefixed to the novel are quoted by Mr. Buchanan in the advertisements of his piece. He might with advantage have recalled two other lines in which the imprecation of Christian is characterized:— From the black depths of man’s despair When a supplication of this kind, the origin of which is implacable hate and its purpose murder, is granted by Heaven, it must, in order to justify the consent, bring with it fatal consequences. The maxim has held good since the beginning of the drama. Putting aside this point and judging ‘Storm-beaten’ as an ordinary melodrama, praise may be bestowed. The piece has at least the elements of enduring success. It would be much strengthened by the excision of a situation in which a girl confesses to an unmarried friend that she has been seduced. To intrinsic improbability this scene adds the disadvantages of being superfluous and of depriving of a certain measure of its power a stronger scene which follows. Points important to the audience are insisted upon over much, a fault not far removed from a virtue, and the wooing of Priscilla by Christian is far too conventional. Everything that scenery and dresses can do has been done for the play, and a fairly efficient cast has been provided. When, however, the heroine comes on the stage singing a well-known berceuse of Gounod an anachronism is committed. The period being the commencement of the century, an air from Gluck, such as “J’ai perdu Eurydice,” might with advantage be substituted. Mr. Warner looked the character of Christian Christianson, and, but for the fact that his wooing was deficient in sheepishness, acted it satisfactorily. He was spasmodic and uneven, but was picturesque and, at one or two points, impressive. Miss Amy Roselle played with much pathos as Kate, a character that has been strengthened; Miss Eweretta Lawrence as Priscilla Sefton had a pleasant maidenly bearing; Mr. Barnes did what he could with the unsympathetic character of Richard Orchardson; and Mr. Beerbohm Tree gave a striking picture of rustic imbecility as Jabez Greene. Mrs. Billington, Miss Jecks, Mr. Proctor, and Mr. Edgar were adequate to their respective parts. ___

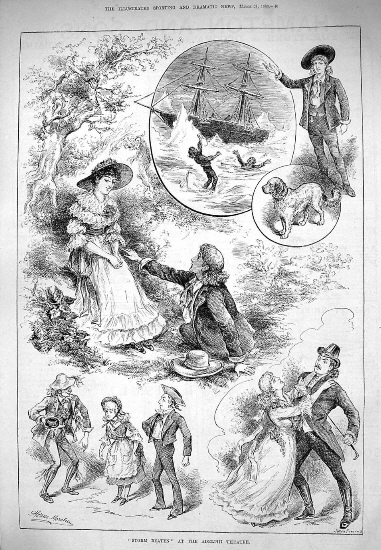

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (24 March, 1883) |

|

|

The Entr’acte (24 March, 1883 - p.6) THE THEATRES. ADELPHI. As a rule, the most successful plays are not those that have been adapted from novels; but this rule does not apply to “Storm-beaten,” produced at the above theatre last Wednesday evening. Robert Buchanan is the author of both romance and drama, and with a knowledge of his own intentions, such as no other person could have, the stage adaptation is thoroughly skilful and artistic. The object of the author is to show how little human hate and vengeance can avail, even under the gravest provocation, and that we are not to be our own avengers. From their youth Christian Christianson and Richard Orchardson have been enemies, and in the prologue, Squire Orchardson evicts the Christianson family from their farm, of which, by unfair means, he has become the owner. Christianson’s wrongs come to a climax when he discovers that young Orchardson has ruined his sister, Kate Christianson. He makes a solemn vow to kill him, and for this purpose secretes himself in a ship in which Orchardson starts on a journey. An iceberg causes the ship to be wrecked, and the two men are cast on a desolate and icy coast. Here Christianson struggles with his enemy, and pushes him into the water, and for some time believes him to be drowned; but Orchardson subsequently appears before him in a starving and miserable condition, and at last Christianson permits him to enter the hut he has built, and tends him during his illness, which ends fatally. But before his death they become friends, as Christianson can withhold his forgiveness no longer. In the story the gradual softening of his heart is well described, but for stage purposes this has to be shortened. Mr. Buchanan in the play has thought fit to change this part of the plot. Both men are rescued, and on their return home Orchardson, in spite of his cruel treatment, is affectionately received by the forgiving Kate. This alteration we consider a decided mistake, as poetic justice demands some more drastic treatment of the villain. Mr. Charles Warner is a manly and vigorous Christianson, and some very pretty scenes occur between him and Priscilla Sefton, a sweetly conceived character, and played by Miss Eweretta Lawrence with much refinement and grace. Mr. Barnes has the unthankful part of Richard Orchardson, and Miss Amy Roselle lends pathos to the character of Kate Christianson. We must not forget to mention the excellent embodiment of Dame Christianson by Mrs. Billington. Too much praise cannot be given to Beverley’s charming landscapes, or to the excellent scenic effects throughout the piece, which deserves to have a good run. ___

The Illustrated London News (24 March, 1883 - p.9) THE PLAYHOUSES. At the Adelphi Theatre Mr. Robert Buchanan, poet, essayist, and novelist, has achieved greater success than has hitherto been his lot as a dramatist. “All things come to him who knows how to wait,” says the French philosopher; and, having bided his time with commendable patience, Mr. Buchanan finds his reward in the public approval at once bestowed on his powerful drama of “Storm-Beaten,” a dramatised version of one of his own novels, bearing an oddly fantastic title. “Storm-Beaten” is a play of the sterling Adelphi pattern—a weird story of a vendetta, culminating, however, in a happy dénouement. A feud, almost Corsican in its intensity, has raged for generations between two country families—the Orchardsons, who are gentlefolks, and the Christiansons, who are yeomen. Richard Orchardson betrays and abandons Kate Christianson; and her brother Christian Christianson devotes all his energies to the un-Christian task of revenge on the man who has done his sister wrong. His desire for vengeance is quickened by the knowledge that the girl whom he himself loves is being sought in marriage by Richard Orchardson. The avenger follows the wrongdoer by land and sea to the uttermost ends of the world, and, to use an Americanism, “kinder freezes to him.” The pair are shipwrecked in the Arctic ocean; and, after many hairbreadth escapes, are cast on an island of which they are the sole tenants. Christian has now his enemy at his mercy; but he timeously relents, forbears to slay him, forgives him in a spirit worthy of his own name, and tends him in sickness. The reconciled foes are picked up by a passing vessel, and return to England. Richard Orchardson makes the amende honorable to the damsel whom he has so cruelly wronged; Christian Christianson weds the girl of his heart; and everybody is happy. Virtue is rewarded, and vice is only left unpunished because it becomes penitent, and makes amends for its past wickedness. The drama thus points an excellent moral, and one which is, to a great extent, novel in melodramas of the hatred and revenge type. In the powerful acting of Mr. Charles Warner and Mr. J. H. Barnes, as Richard and Christian, of Miss Amy Roselle as Kate Christianson, Miss Eweretta Lawrence as Priscilla, the beloved of Christian, and the alert Miss Clara Jecks as a village flirt, Mr. Buchanan’s forcibly eloquent dialogue found apt exposition. The sylvan and arctic scenery, by Mr. William Beverley, is very beautiful; and altogether Mr. Robert Buchanan has full reason to congratulate himself on the first voyage of his “storm-beaten” but at length safely-harboured ship. ___

The Sporting Times (24 March, 1883 - p.2-3) PLAYHOUSES WITHOUT PLAYS. BROADSTAIRS does not suit Blobbs’ lungs, and Dr. Jope is in despair. Poor Peter is low, and yet his complaint does not yield to all the nourishment contained in a matutinal gallon of milk mixed with a quart of wholesome rum. He has now been recommended to try his native air, and may accordingly be found patrolling the Whitechapel Road every afternoon. But in vain, and we, his loving friends, consult as to the system of treatment most likely to restore him to his former state of youthful health and beauty. “I WOULD suggest a few days hunting,” says the Usurer, whose experience of the sport is limited to what he has been able to acquire from the inspection of a few gaudy-coloured waistcoats. “Or a week’s fishing,” says the Windsor Warrior, who never saw a salmon, except at dinner-time or in a shop window. The Shifter thinks change or diet, and the Child unselfishly proposes a voyage round the world—she thinks that she could bear a temporary separation, even if Blobbs could not. After the others have given their respective opinions, it is my turn, and, while agreeing with the Child that Blobbs’ prolonged travel might perhaps benefit the community, I venture to suggest that a too constant attendance at the Gaiety may have shattered our friend, and that a return to legitimate and enlivening melodrama may have the effect of restoring Blobbs’ dilapidated system. THIS is why we find ourselves at the Adelphi Theatre, the original home of wholesome melodrama. Robert Buchanan, a Scotch poet, has written a new and original drama which he wanted to call God and the Man. But the licenser of plays, with more regard for decency than most public officials, except Mr. Justice North, apparently possess, declined to permit such pandering to the increasing popularity of blatant blasphemy. The play is now entitled Storm-Beaten. THE prologue introduces us in the Widow Christianson’s house to all the important persons of the drama—stage widows always have the same sort of houses. This cottage resembles Widow Melnotte’s, only there is no easel. Mrs. Christianson has two children, a daughter and a son. “If she had a thousand,” grumbles Blobbs, “she could not expect greater ‘variety.’” Widow is unhappy because she owes money, which she can’t pay, to one Squire Orchardson. It is not exactly this that makes her miserable, it is rather the fact that Orchardson is coming down like a wolf on the fold, and is going to pay himself by taking possession of the Farm. Mrs. Christianson tells her daughter, Kate, that the Orchardsons have been their vindictive enemies for several generations, and proceeds to violently vilify this particular Squire. “It is always thusly,” sighs the Usurer; “whenever a chap owes you money and cannot pay, he invariably calls you a scoundrel if you ask for it back.” WHEN the widowed mother retires to weep (widowed mothers always weep in melodrama), Miss Amy Roselle, who is daughter Kate, receives her lover, Mr. Jack Barnes, who is Orchardson junior. Considering that a feud has always existed between the families of Orchardson and Christianson, the intimacy between these two young persons appears sufficient to induce a belief that it will soon be made up. And so it would, if Jack was as good as his word. But he is a bad, bold man, who makes only a naughty love to Kate. He is so intimate that he does not ever take his hat off in her presence. His dark-green coat and brass buttons and cross-belt makes him look like a Forester going to a fête at the Crystal Palace. Footsteps are heard, and Barnes departs. ENTER Charles Warner as Christian Christianson, the widow’s son. Mr. Buchanan might have chosen a nicer name for his hero. But he takes the opportunity of making a feeble joke, saying that the man ought to be a good Christian, and he might as well have called him Jew Jewson, and have recommended him to be a good Jew. Throughout the whole play there is a flavouring of mock piety, to which all who have sincere respect for true religion must object. Biblical allusion and quotations from Holy Writ are out of place on the stage, and just at the present time public writers in every department would do well not to bring in false garb, and in theatrical spirit, that which was intended, and is employed by right-minded persons, for unostentatious reverence. Religion is no subject for glittering advertisements. Poor Charles Warner, however, is not to blame. He struts upon the stage, with his head well thrown back, and, as is his wont, casts his eyes upon the chandelier of the theatre with the interest of a Defries, and he keeps them there. Mr. Warner is a conscientious actor, and a good one too, but I cannot help comparing him to the oxyhydrogen bag, which is inflated afresh every night, and is used up by the end of the performance. His speeches always seem to escape from him, in spite of strenuous efforts by him not to part with them. In all his characters he commences hale, hearty, and stout, and before the completion of the performance some unfortunate weakening process takes place. Just now he has been to the lawyer to ask time for payment of the debt due to Orchardson, and it has been refused. A LADY, who has lost her way, arrives at the window’s cottage. She is a nice-looking young person, but appears to be just a bit of a flirt, for, instead of moving on when she has obtained the required directions, she remains to talk with Mr. Warner. She tells him that her name is Eweretta Lawrence, and also other particulars which hardly concern a stranger. Blobbs intends in future to leave the door of his castle open, in case any more young ladies should stray from the right path and require assistance. Presently some shouting is heard outside, and a blind parson (his eyesight is gone—I don’t mean that he is intoxicated) comes into the cottage, followed by a hooting mob. Parson is Eweretta’s papa, and passes his time perambulating other people’s parishes preaching. The crowd has very properly resented a poacher on the preserves of its own particular pastor, and the old man looks like having a rough time. Warner, like the good Christian Christianson that he is, tries to induce a real St. Bernard dog to fly at the crowd. Bow-wow firmly declines, but the mob disperses just as quickly as if its leader had been attacked by Hubert, the alleged saviour of the life of Lady Florence Dixie. What a pity it is that Hubert cannot speak. To use the language of Arthur Roberts, “It would be d——d funny.” “I ONCE knew a parson,” says the Usurer, “a fine old sportsman, who had a nice fat living in Blankshire. He used to come up to London all the week and enjoy himself like a bonny boy. But he always returned to his vicarage on Saturday afternoon. One Saturday, I think it was the first night of a new burlesque, I begged the old chap to stay in town. ‘Can’t you get anyone to do your duty, just for once?’ I asked. ‘No; impossible,’ said his reverence, mournfully. ‘For twenty years I have never missed a Sunday, and my reason is this,’ he added, quite confidentially. ‘If my congregation heard a new man I don’t believe they’d ever stand the old boy again.’” While we have been listening to the Usurer’s story, which we have all heard a dozen times before, Miss Eweretta Lawrence has taken her papa away. Squire Orchardson has called and demanded the money owing to him—he is as grasping as a Dublin Alderman. Orchardson, junior, has shot Warner’s dog (a most unnecessary precaution, for the beast was absolutely harmless). The widow has taken a Bible and tried to induce her children to swear on it a vindictive, blasphemous oath. Miss Amy Roselle, like Ole Brer Bradlaugh, declined to take the oath; but it escaped jet by jet from oxyhydrogen Charley. And the curtain has descended. ALTHOUGH chosen as Queen of the May, Miss Roselle feels her unfitness for that proud position. When some ladies are singing a song that sounds like a feeble imitation of “Over the garden Wall,” Miss Amy unfolds her woes. Alas! she has loved not wisely but too otherwisely, and he wont marry her after all, the brute! She will leave her home and go out into the world. This is a stupid proceeding but a common one. “When in trouble stop at home,” is the Usurer’s advice. Poor Amy, however, cannot stand the disgrace. So she kneels down and confides in Miss Lawrence. “Eweretta,” she sobs,” I am ruined.” Ewer— what?” asks the astonished lady; and so the story comes out, but no names are mentioned. By this time Charley Warner has fallen in love with the parson’s daughter, and so have I. She is a sweet, unaffected actress, with a melodious stage voice, a graceful deportment, and, for her limited experience, shows unusual knowledge of stagecraft. When I took Master to see her play Pauline I thought she was going to be a somebody at her profession, now I am sure of it. Orchardson, junior, also wants to marry her, and these two enemies are each afraid of the other. When Eweretta tells Charley of his sister’s shame, he is so deeply affected and so vigorous for vengeance that I begin to fear the gas wont hold out, and that he will have to be refilled in the entr’acte. So far the play is monotonously jumpy. IT may, perhaps, be impertinent to surmise as to the private feelings of an actress after her stage work is over. But I sometimes try to picture Miss Amy Roselle in her domestic life. Can she ever know a moment’s rest? Every terrible disaster that human flesh is heir to has fallen upon her in the course of one play or another. The strain upon her nerves must be dreadful. When she dreams, though I hope for her own sake that she never does, her nightmares must be horrible. No woman has undergone such astounding accidents. She has been blown up and blown down. The number of perfidious lovers who have wronged her is only equalled by the number of children she has mourned over. She has suffered the misery of a drunken husband, and has frequently perished with cold and starvation. I don’t think that even a Fenian head-centre could conceive any new torture for her, and yet she plays on—calmly, earnestly, and pathetically. BLIND PARSON and Eweretta have been staying with the Orchardsons, and are now going a sea voyage. Good-byes are being cordially exchanged all round. Charley Warner has had rather more than his share of them, and so Orchardson, junior, is jealous, and announces his intention of accompanying the travellers. When they have left, Miss Roselle appears; her child is dead, and she has rather a rough-and-tumble with Orchardson, who very properly declines to marry her. If young ladies misbehave themselves, they must be “treated as such.” When she faints away her brother brings her to, and she discloses the name of her quondam lover. Then Charley Warner, with the gas at the highest possible pressure, gives vent to a fearful and wonderful oath of vengeance against Richard Orchardson Barnes, Esq. Curtain. Why does not some enterprising melodramatist present his wronged lady with twins, or even triplets? One child only at a time is such a commonplace incident. Henry Pettitt, Paul Merritt, and Augustus Harris are welcome to this suggestion gratis. ON board the brig The Miles Standish. “What a wretched sort of craft for people to take a pleasure trip in, to be sure,” says Blobbs. “Mr. Proctor sings a comic song, but I cannot hear what it is about.” “Rather bad luck,” observes the Usurer, “considering that this is the first attempt at comicality in the bally play.” Charley Warner in disguise has tracked his foe here. When he commences an attack, the skipper of the ship puts him in irons down a trap. Orchardson thereupon sets the ship on fire. “Barnes is always setting something on fire,” observes the Failure. “In Pluck it was a house.” “In Macbeth it was not the Thames,” retorts Blobbs, sententiously. His present proceeding is hardly sensible, considering that, if successful, he will not only kill his enemy, but also himself and the lady he professes to love. Rather weak this, Mr. Buchanan. But the fire is put out, as a huge iceberg comes down on to the ship. “Where is it supposed to be?” asks the Usurer. “Are we in Eurup, Asiup, Africup, or Americup?” “None of those,” says Blobbs; “can’t you see the ice—we are at Gatti’s, of course.” IF Augustus Harris, or even Wilson Barrett, had been entrusted with the production of a play with a scene such as the one now in process of change we should have had a picture worth talking about. Messrs. Gatti, I should have thought, were the people above all others most competent to produce picturesque ice scenes. In this one they have failed, and given just an ordinary canvas or two which look like nothing else, with some coloured lights at the back, thus presenting a striped appearance similar to Neapolitan ice. Even these effects cannot be carried out without the temporary dropping of a curtain of black gauze, which is rather provoking at an interesting moment. It rises in time to show us the ship sail away, while Warner and Barnes fight until both fall into the water. ACT IV. Irreverently described in the programme as “Alone with God.” When the licenser changed the name of the play he ought to have looked at the titles of the acts. Nearly all the gas has escaped from Warner, who is now weak and starving on a desert island with Barnes. Poor old Robinson Warner, there is no one for him to Crusoe with but his enemy, who has been very ill. No matter how handsome Jack Barnes tries to make himself up to look miserable, no matter how much he powders his beard and tries to be woebegone and unhappy, he still looks a hale, hearty, and well fed young gentleman. His clothes are shabby, truly, but they were in execrable taste when new, so that he would have required another suit whether he had been wrecked or not. MR. WARNER falls asleep and dreams a vision. Out of a hole in the scenery appear Misses Amy Roselle and Eweretta Lawrence walking arm-in-arm. Although this is not half so well done as the vision in the first act of Little Doctor Faust, it wakes Charley, he wakes Barnes, and the two make up their little differences. Blobbs thinks that this would be a good opportunity for a dance. Very likely we should have a recitation about Wolsey’s death, only some people who were rowing on the Serpentine have lost their way and pop in unexpectedly at the Desert Island, and its oldest inhabitants do them the honour to go away in their boat. THE next and last act brings happiness to everyone, including the audience. Barnes makes restitution by marrying the girl. Eweretta, of course, marries Warner, and the church bells ring. This is the whole play. It is a very miserable one, and unrelieved by those sensational but laughable incidents which are the principal excuses for melodrama. Mr. Beerbohm Tree acts the small part of a semi-idiotic shepherd; he does not seem to understand what was expected of him. It is not surprising, for the character is inexplicable. Miss Jecks is also a figure introduced for no adequate reason, unless to show how much better she looks in her own bright, black hair than in a yellow wig. Instead of reviving Blobbs, Storm-Beaten has nearly killed him. There are some advantages in the drama, after all. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (26 March, 1883 - p.2) Mr Robert Buchanan has taken the Globe Theatre, with the view of producing a new play which he has written, but which has not yet been named. The right of performing “Storm Beaten” in America, which Mr Buchanan sold for £600, has just been resold for £2000—the increased value being due to the favour with which the play has been received in London. ___

The Dundee Courier and Argus (2 April, 1883 - p.3) I hear that Mr Robert Buchanan will receive £2500 for the American rights in “Storm Beaten.” The whole of this money will not, I believe, reach the pockets of the author. ___

The Theatre (2 April, 1883) STORM-BEATEN. A new and Original Drama, in a Prologue and Five Acts, by ROBERT BUCHANAN. Produced at |

|

|

|

MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S novel, called “God and the Man,” is remarkable as much for the power of the story as for the eccentricity of the dedication attached to the book. The author calls his romance “A study of the vanity and folly of individual hate,” and proceeds to dedicate it to an “Old Enemy.” The old enemy was none other than Dante Gabriel Rossetti, poet and painter, now no more, and with whom it could scarcely be supposed that Mr. Robert Buchanan would have very much in common. Their ways are divergent; their songs are set in a distinctly different key; the art they respectively followed was inharmonious; the earnestness of the creed of each sprang from a different source. It would have been strange indeed had two such men sympathized in anything appertaining to art or poetry. It may be interesting, however, to quote Mr. Buchanan’s general confession or apology, in which he frankly owns to have misunderstood the bent of Rossetti’s mind and the distinct quality of his genius. There was scarcely any need for it. We do not look for regret from the order of mind that expresses its disapproval of Rossetti’s art, his colouring and his pictures by explosions of derision and ill-restrained laughter. The Philistine will remain the Philistine until the end of the chapter. You cannot cure the blackamoor of his skin or the leopard of his spots: it would be a needless waste of time to do so. To sympathy with Rossetti and his school is not after all a matter of education, but of predilection. It is not acquired taste; it is inborn refinement and the possession of the higher qualities of imagination. Still it is interesting to learn even of the conversion of Mr. Robert Buchanan. TO AN OLD ENEMY. I would have snatch’d a bay leaf from thy brow, Pure as thy purpose, blameless as thy song, The second dedication is dated August, 1882, and is addressed direct to DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI. Calmly, thy royal robe of Death around thee, I never knew thee living, O my brother! The story of “God and the Man,” at first sight lends itself admirably to the purpose of the stage, though it does not necessarily follow that a novel written with dramatic effect will on that account evolve itself into a play. In a picturesque period of the last century we see the latest signs and the last bitter fruit of the hereditary hate between the Christiansons and the Orchardsons of the Fen country. The last heirs of this horrible quarrel are found in Christian Christianson, a fine manly representative of the English farmer, and Richard Orchardson, the refined and delicate son of the rich squire of the parish. The parents of both boys daily feed this feud. It is essentially requisite, however, to keep in view, and strongly in view, the physical disparity between the two lads. The author is careful to emphasize it, when he depicts a famous scene where Christian Christianson thrashes Richard within an inch of his life for killing a favourite dog. The bad blood engendered is made to boil by means of the lash, and Richard bears a lifelong mark of the terrible encounter in boyhood. But quarrels as fierce as these might be softened but for the occasionally outspoken influence of women. In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred where men fall out and would be reconciled again, it is the hidden and secret influence of a vindictive woman that prevents the healing of the wound. “Hell has no fury like a woman scorned.” Quite true; and as often as not she takes it out by nursing the feud that it should be her nature to heal. But it is no serpent amongst the branches of the family tree, no asp in the basket of figs, that stings the Christianson contention. Women are the unhappy accident that turn a simple hate into a determined savagery as between man and man. Christian’s sister has fallen under the spell of his old foe Richard, and been ruined by him, and, as if this were not bad enough, both men passionately love the same woman. This girl is a charming character, one Priscilla Sefton, the daughter of a blind wandering preacher, who devotes his life and his income to saving souls, in the primitive fashion adopted by his master, John Wesley. The mixture of puritanism and poetry in this girl is very delightful; she is as natural as she is novel in fiction, and is a refreshing feature of the painful story. With much art the novelist is able to elaborate the incidents of the seduction of poor Kate Christianson, her desertion by her base lover, and her miraculous preservation from death by the good Priscilla, who has innocently aggravated the quarrel by inspiring love in the breasts of both these men. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (24 April, 1883 - p.7) We have just heard that a long and exasperating correspondence has been going on for some time past between Mr. Robert Buchanan, the author of the popular Adelphi drama “Storm-Beaten,” and the Lord Chamberlain, touching certain features of that play which are supposed to entrench upon ground with which the theatre is thought to have no rightful concern. When the two men whose life-history makes the backbone of the drama—Christian Christianson and Richard Orchardson—are cast away together on a desolate island, the object of the dramatist is to show that under the shadow of a gradual and dreadful death the old fierce hate that has subsisted between these two enemies gives way before the new birth of a brotherly charity. They are together, but they are dead to all the world; they are “alone with God;” and these words are used in the playbill to denote that terrible isolation out of which the good spirit of forgiveness is born. The Lord Chamberlain, however, objects to the use of the words as being beyond the phraseology proper to a playhouse. Nor is this all. When Christianson and Orchardson return from sea, and reach the village wherein they were bred up to manhood together, it is Easter Day, and the choir of the old church are singing the Easter hymn. There is a dramatic propriety as well as a dramatic beauty in the incident, for—let us say it with due reverence—are not these men also newly arisen from their long burial? But the Lord Chamberlain considers this a “needless profanity,” which must be removed. And so, as we say, it seems to be the set purpose of the time that the influence of the theatre shall not be “wider than it ever was.” The stage is told again and again to keep within its own limits. It may make itself a sort of serious Punch and Judy show to exhibit the little loves and squabbles of domestic farce, comedy, tragedy, pantomime, perhaps harlequinade; but as for bringing “influence” to bear on life—that is none of its business. |

|

|

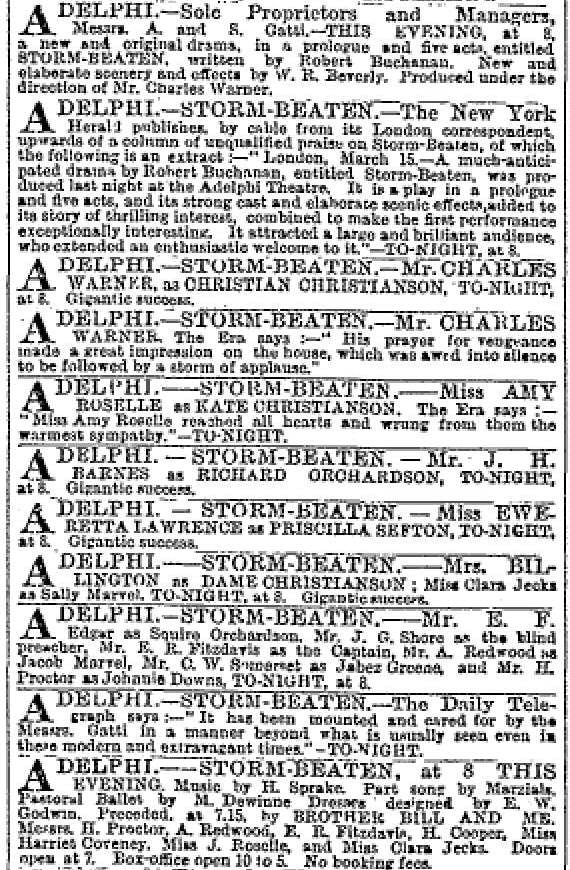

[Advert for Storm-Beaten from The Times (17 April, 1883 - p.12).]

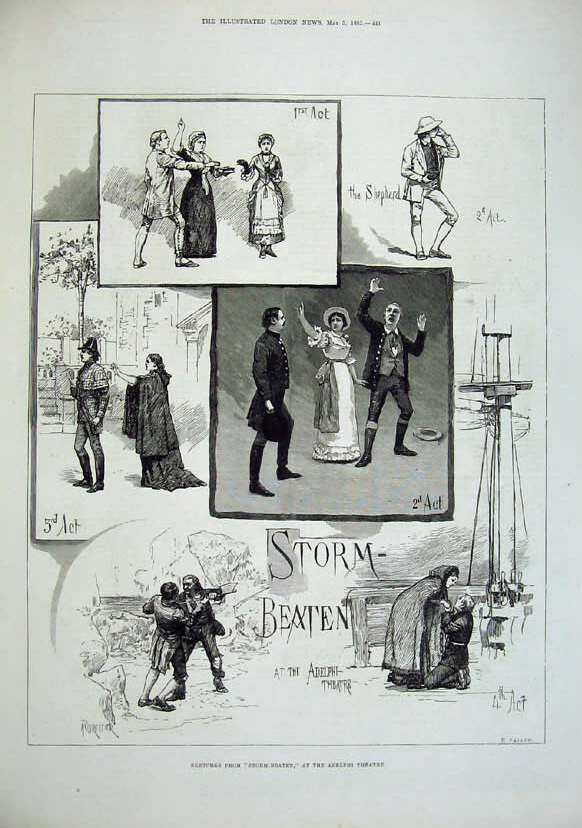

The Illustrated London News (5 May, 1883) |

|

|

“STORM-BEATEN” AT THE ADELPHI. This powerful melodramatic play, which Mr. Robert Buchanan has constructed from the story of his striking novel recently published under a different name, continues to prove interesting to the popular audiences at the Adelphi Theatre. It seems intended to be a forcible illustration of the futility as well as impiety of cherishing an implacable purpose of revenges for the most enormous personal injuries. We see that the hero, Christian Christianson, while pursuing on the high seas his design of vengeance upon Richard Orchardson, the seducer of his sister Kate, and his rival in the affections of Priscilla Sefton, is thrown by shipwreck, together with the villain above-mentioned, on a desolate Arctic shore, where they share the prospect of a miserable death, and are deprived of the inducement to gratify their mutual hatred by killing each other. Mr. Charles Warner in the part of Christian, and Mr. Barnes in that of Richard, act up to the intense spirit of enmity, in this prolonged duet of aggravated ill-will, with considerable force of expression; while the distressing position of Kate and the innocence of Priscilla, respectively performed by Miss Amy Roselle and Miss E. Lawrence, bring into sufficient prominence the play of feminine affections. Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s amusing representation of the silly shepherd, Jabez Greene, gives some relief to the exhibition of woes and wrongs and tragic passions; and the scenery, painted by Mr. Beverley, affords some grand pictorial effects. Our Sketches of “Storm-Beaten” are a delineation of some of the notable characters and incidents of this dramatic romance as shown upon the Adelphi stage. In the first Act Mrs. Christianson is represented obliging her son and daughter to take an oath that they will avenge the family wrongs; the other scenes will be recognised by all who have seen the play or read the book, and those who have not may do so if they please. The title of Mr. Buchanan’s original romance was “God and the Man”; but considerations of propriety forbade the retention of that name in the announcement of a theatrical performance. ___

Truth (26 April, 1883 - pp.3-4) I OBSERVE with much amusement that Mr. Robert Buchanan is exhaling his indignation at my not being an admirer of his two plays, “Storm-Beaten” and “Lady Clare,” in advertisements in the daily papers. I suppose that this sort of silly person really is of opinion that any one who ventures to regard these plays as inferior to those of Shakespeare, is either a fool or a knave, and far be it from me to object to his devoting his money to making public this singular illusion. Some years ago, Mr. Buchanan published a poem called “Uncle Abe.” Without being a very wonderful production, it had its merits. Since then he has published novels and written plays. In all of them the heroes appear to be actuated by the meanest and most contemptible feelings; they are dismal, dreamy, dull, drivelling dolts, without one manly instinct or one healthy impulse. And yet Mr. Buchanan seems to admire them as much as he admires himself. “Storm-Beaten” has excellent scenery, and is well acted. To this alone it owes such success as it has achieved. As for “Lady Clare,” I do not hesitate to say that it is one of the worst plays ever written. Lacking, I suppose, the inventive power, Mr. Buchanan has strung together a number of scenes culled from various plays, and done his best to spoil them. To call this sort of joiner’s work authorship is an abuse of words. |

|

|

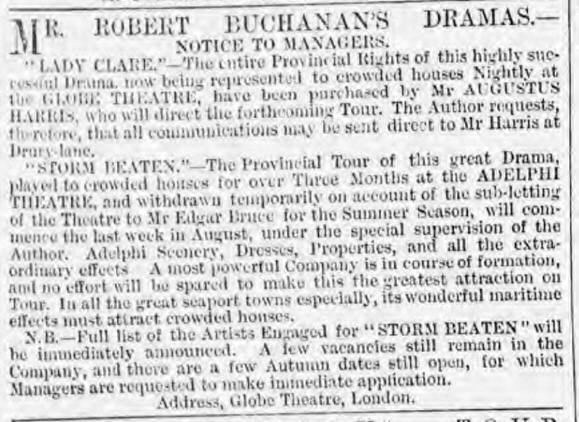

[Notice in The Era (9 June, 1883 - p.17).]

New-York Daily Tribune (16 June, 1883 - p.5) THE UNION SQUARE AND JOHN STETSON. TROUBLE IN REGARD TO ENGAGING CHARLES WARNER Two persons well known in theatrical circles were discussing recently matters of local theatrical gossip. ___

New-York Daily Tribune (8 July, 1883) MISS DOLARO’S NEW PLAY.—Selina Dolaro has sold her comedy to Shook & Collier of the Union Square, and they are quite enthusiastic about it. Miss Dolar is more modest, however, and does not want anything said about it yet awhile, “as it is not to be done until after the run of ‘Storm Beaten.’” That will in all probability be a very short one, for “Storm Beaten” appears to be a stupid sort of heavy drama which Collier bought at the round price of $10,000 much as he might have bought “a pig in a poke” or accepted a gift horse, without looking at it. It is to be hoped that Mr Collier has not made as big a mistake in this selection of “Storm Beaten” as in his judgment of “Coney Island,” for laughing at which farce he still blames his friends. Miss Dolaro is to perform in her comedy, but what sort of a part, the fair opera bouffe artist refuses to tell—“just yet.” ___

Davenport Weekly Gazette (Iowa) (22 August, 1883 - p.12) Robert Buchanan intends to come to America next Winter to supervise the performance of a play made out of his “God and Man.” ___

The Dundee Courier and Argus (28 August, 1883 - p.5) Mr Robert Buchanan will probably visit New York some time before the production of “Storm Beaten” at the Square. ___

The Era (15 September, 1883 - p.6) THE PAVILION. On Monday, September 10th, Revival of the New and original Drama, Squire Orchardson ... ... ... Mr. C. H. STEPHENSON Since melodrama has become the vogue at the West-end, and the love of exciting incident and well-seasoned sensation is as strongly developed in Belgravia as in the Mile-end-road, it is only in the natural sequence of events that the successes of the Strand should be repeated in Whitechapel. In their turn Pluck, Love and Money, with other pieces belonging to the same category, have been revived at this house with highly encouraging results; but we doubt if any one of the late revivals has secured the enthusiastic reception given to Mr Robert Buchanan’s Storm-Beaten at its initial performance here on Monday night. On the production of the play at the Adelphi it was a greater pleasure to us to congratulate the author on his success, since it was obtained in spite of repeated and discouraging failure. Yet Storm-Beaten by no means can be called one of the most sensational of plays. There is no horrible crime; not a pistol shot is fired nor a drop of human blood shed. We have a simple pastoral tale, told in graceful and elegant dialogue, of the hatred existing between two families, or rather two young men representatives of those families; the one proud, high-spirited, and quick to resent insult; the other arrogant, avaricious, and cruel. The author, by somewhat extraordinary means it may be, brings these two together on a desolate island, the oppressed being determined to kill the oppressor. But the flood of gentle and hallowed pity overwhelms relentless and unreasoning hate, revenge gives way to softer emotions; the wronged tends the evil-doer in the delirium of fever, and, with weak and tottering steps, it is the injured that takes the aggressor in his arms to the boat that saves them both. There are plenty of strong scenes throughout the play, but this is certainly the strongest, in that it is the most intensely human. The heroine, generally distressed and unhappy, makes heavy demand upon the sympathies of any audience; but the author seems to have been at greater pains in the drawing of another character, a wandering preacher’s daughter, who carries her religion into daily life, and is ever at hand to counsel kindness, gentleness, charity, and forgiveness. This Priscilla Sefton is, indeed, a most charming creation. Provided with the Adelphi mounting and effects, it may be readily imagined that the two pastoral scenes called forth considerable applause, while the storm of approbation which greeted the pretty tableau of the ice-floe, one of the most effective stage pictures that could possibly be seen, was thoroughly well deserved. Those responsible for the stage business might, however, have known better than to introduce the well-known Easter hymn when the hero talks of Christmas bells. The audience were, perhaps, scarcely educated enough in Church matters to notice this, but it is an anachronism that can be, and should be, speedily rectified. Of the acting we can speak in terms of praise. Mr Edmund Tearle, an actor, we think, who makes his first appearance here, undertakes, with gratifying success, the part of Christian Christianson, the hero, played by Mr Charles Warner at the Adelphi. A natural anxiety probably at times led Mr Tearle to exaggerate, and therefore to force his voice beyond control until it became harsh. This was especially the case in the curse scene. A little “reserved power” in the earlier phrases would have increased the effect of the concluding words, until they became a very torrent of passion. Mr Tearle’s diction would also gain were he to suppress a tendency to anticipate his words. This is a mannerism that suggests staginess, and should be at once got rid of. He, however, enchained the house in the curse scene, and the agony of apprehension that Christian experiences when he thinks to lose the companion of his desolate solitude could not have been better expressed. Buoyancy also marked his share of the earlier scenes with Priscilla, while the love for his good genius was artistically shown. Mr A. C. Lilley made an admirable and self-contained Richard Orchardson, gave powerful effect to his share of the scene on the island, and altogether acquitted himself well of an exceedingly uphill task. The Kate Christianson of Miss K. O’Connor secured throughout the entire sympathy of the house. Poor Kate is compelled to wear a smiling face under her crown of flowers while her heart is heavy with a load of shame. Miss O’Connor’s great opportunity came when Kate, coming face to face with her seducer, tells him of the loss of their child and implores him to keep his promise to make her his wife. The audience were much moved during this scene, and there could be no doubt of the actress’ success. Miss Ellen Beaufort looked a gentle Priscilla Sefton, playing the part in an unaffected manner. The dignified tone assumed in the speeches of rebuke to the overbearing Orchardson or the hot-blooded Christianson never failed of its effect, and the archness and vivacity of the love scenes told well with the house. The Dame Christianson of Miss Harriet Clifton was an impressive impersonation. The dignity of the Squire lost nothing in the hands of Mr C. H. Stephenson. Mr George Yates made an efficient sailor Johnnie Downs, though he can scarcely be considered an able singer. The part of Captain Higginbotham derived additional importance from the excellent manner in which Mr Wallace Moir played it. This Captain became quite a popular character, so full of quiet humour was he. Though the scene of the drama is laid in the fen country, Mr Eardley Turner made Jabez Greene a shepherd of Salisbury plain. However, his uncertainty as regards dialect must be forgotten in view of the droll stupidity which he infused into the part. The dairymaid Sally Marvel, a sort of country soubrette, found a lively and satisfactory representative in Miss Letty Lind; while the fanaticism of the cobbler Jacob Marvel was efficiently indicated by Mr Arthur Chudleigh. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (2 October, 1883 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s play of Stormbeaten, his first great financial success as a dramatist, has been revised for the American stage, the dialogue and some incidents altered, and the American copyright sold for £3,700. ___

The New York Times (18 November, 1883) The closing up of the Union-Square Theatre during the coming week is purely to prepare for the production of “Storm Beaten,” which is a play that will, in some respects, test the capacity of this stage as it has never been tested before. Mr. Jefferson could easily have done another week of very large business, and would have liked to do so, instead of jumping his costly company from here to Chicago, as he will now be obliged to by the limited express train this morning. The Jefferson company rented the Union-Square Theatre outright, instead of sharing with Messrs. Shook and Collier. The members of the regular Union-Square organization will have a tumultuous week from now on. They will play every night in Brooklyn, and rehearse every day in New-York. They are already under good discipline as to the plain sailing business of their parts, but they have now to work with the scenery and properties to be used in the play. These will be more extensive and elaborate than any that have ever been employed in any production upon this particular stage. As the managers are limited for space, the most careful preparation of the smallest details is demanded. One of the sets will be particularly hard to handle. It represents a ship caught in a vast ice-floe, which breaks up at the end of the act, allowing the vessel to sink into the water and float off. It was difficult to make this effect realistic, even upon the large stage of the Adelphia in London, where “Storm-beaten” was originally brought out and within the confined space of the Union-Square, the task is made doubly hard. But Mr. Marston, Mr. Cazauran, and the carpenters have exercised their ingenuity to its utmost, and Mr. Collier has expressed himself as satisfied with the result. The device of pasting mica upon the canvas to give the polished, brilliant surface of real ice, has been tried and is said to work well. Much is expected of this effect. The other strong scenes of the play, from the painter’s stand-point, represent the deck of an ocean vessel and the interior of a church. The latter scene will embrace the close of the play, which has in this respect undergone considerable alteration from the original, at the hands of Mr. Cazauran. The story formerly ended in a graveyard, and was not, in this respect, conducive of cheerful thoughts to go to bed on. Mr. Cazauran has arranged to finish the play with a double wedding. Mr. Rankin, who is to play the hero, has been subjecting himself to the process usually followed by Prof. Sullivan when preparing himself for the knocking out of ambitious citizens, and there has been a consequent falling away in Mr. Rankin’s abdominal regions. His mustache, which was the joy of his soul, has likewise gone the way of things that must be sacrificed to the cause of rejuvenation, and Mr. Rankin now seems a rather jolly, round-faced youngster, whose conversation suggests experience beyond his years. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (20 November, 1883 - p.2) “STORM-BEATEN” AT THE ROYAL LYCEUM THEATRE. Mr Robert Buchanan has attained the distinction in contemporary literary history of having succeeded pecuniarily as a dramatist where considerably greater poets have more or less completely failed. Some playgoers after seeing “Storm Beaten,” however, may doubt whether it would not be more creditable to fail with Tennyson and Browning than to succeed with Mr Buchanan. The kind of success which is attained by exciting one portion of an audience to enthusiasm at the expense of moving another portion to laughter may be a paying one, but it is sufficiently barren of literary honour. In “Storm Beaten,” be it acknowledged, Mr Buchanan has got hold of a really strong dramatic motive. Few modern dramas have such a good backbone as is represented by his idea of a study of “the folly and vanity of individual hate.” But he has chosen to place that idea in the mould of the popular, sensational and spectacular melodrama, and a deep ethical motive is a burden which sensational melodrama utterly refuses to carry. The result of the union of intellectual teaching with the purveying of vulgar excitement is that the former is degraded, while the latter is in nowise redeemed. To effectively work out a good motive there is needed good character-painting, which is simply the making personages talk in a natural manner; and natural talk in a sensational play would be voted exceedingly dull, if not unintelligible, by those who applaud the sensational effects; so that if Mr Buchanan were able to produce natural dialogue, which is doubtful, he would require deliberately to avoid doing so in writing for the Adelphi. What he has done is to use, in the high-pitched scenes, with some little modification, the established language of melodramatic convention, making the characters talk of crushing under the heel and crossing paths; declare that “a time will some,” and apostrophise the deity; while some of the love scenes, on the other hand, are of a gracefully romantic kind that will only appeal to playgoers who smile at the others. As for the great sensation scenes, it can only be said that they are noisily ridiculous to all save the most primitive-minded spectators. The performance last night did the play full justice in some respects if not in all. Christianson, the central figure, had a representative of the stentorian melodramatic type in Mr Edmund Tearle, whose proper place is clearly in a rôle of the heavy villain order; and scenes which might have been made genuinely impressive in the hands of an actor of a higher class were in his simply violent. Thus in delivering his curse—a very complete thing in its kind—he relied purely on physical force, and only succeeded in being deafening. An actor with real powers of passion would have made the curse much more terrible by deep intensity, in which case the actress playing Kate would require to abstain from the prolonged wrestle indulged in last night by Miss Kate O’Connor. As it is, that lady has a vicious physical method of displaying strong emotion in some scenes, though her acting has good points. A very pleasingly played part was that of Priscilla Sefton, filled by Miss Annie Robe with such unfailing good taste and good feeling as presumably to realise the author’s ideal. Mr Courtenay Thorpe as the villain was perhaps more extravagantly stagey than he need have been. Among the minor personages, Miss Letty Lind deserves notice for her remarkably life-like playing in some interludes very clumsily introduced by the author or the stage authorities. ___

The Glasgow Herald (27 November, 1883 - p.4) ROYAL PRINCESS’S. “STORM-BEATEN.” The success of Mr Robt. Buchanan as a dramatic author attracted a large audience to the South-Side Theatre last night to witness the production for the first time in this city of his realistic drama “Storm-Beaten,” recently withdrawn from the London Adelphi after a very remunerative run. As every newspaper reader knows, “Storm-Beaten” is the dramatised version of Mr Buchanan’s novel “God and the Man.” The play is built on old familiar lines, the never-ending conflict between virtue and vice being the central pivot on which everything turns. There is thus necessarily a villain as well as a hero, but it had better be said at once that while the villain is notoriously infamous the hero of the piece is anything but the model man such beings usually are. Inspired by a long-standing family feud, which is deepened by an irreparable wrong done to his sister, the hero (Christian Christianson) pursues the villain (Richard Orchardson) with a hatred nothing short of fiendish. The wavering love of a strolling preacher’s daughter helps to aggravate the breach between the two. The lady and her father set out on a voyage; Orchardson takes a passage in the same vessel in order to press his suit; Christianson is also on board, though disguised, his object being to take the life of the man who had betrayed his sister. One attempt fails, and the would-be murderer is put in irons. It is now the villain’s turn, and he conceives the idea of firing the ship in order to get rid of the man who has come between him and his love. This attempt also fails. Scarcely has the excitement of this affair died away than the ship is wrecked on an iceberg. Face to face with a common death the one man attempts to take away the life of the other, and in the fierce struggle which ensues both are cast ashore on an uninhabited island in the Arctic seas. In this singular situation Christianson relents towards his sworn enemy, who, by the by, is down with a fever or something of the sort. He nurses him as a mother might do, and keeps him in life till the very moment when an exploring party, among the members of which are Christianson’s sister and sweetheart, sets foot on the island. The hero is presumably carried back to the country of his birth. Speaking in general terms, the play can hardly be said to be a great success. It has too many inconsistencies and exaggerations to admit of its having an enduring reputation. It is a gallery piece pure and simple, and with the gallery last night it found much favour. The company of ladies and gentlemen who have been retained to represent the piece is of more than average merit. The scenery and effects are also admirable, being those which were made use of in the Adelphi production. A word should also be said for the orchestra, who, under the able leadership of Herr Franz Grœnings, contributed not a little to the entertainment of last night’s audience. A feature of the selections played between the acts was the fine rendering of “The Lost Chord” as a cornet solo by Mr Wm. Short. ___

The New York Times (27 November, 1883) AMUSEMENTS. “STORM BEATEN.” It is not exaggeration to say that a second part in the career of a famous and brilliant playhouse was opened last night when the thirteenth regular season at the Union-Square Theatre was begun with a performance of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s drama, “Storm Beaten.” For a long while this theatre was managed with remarkable tact, enterprise, and sagacity. It acquired a reputation which was undoubtedly well measured and deserved. Unfortunately, the seasons at this house were cut shorter and shorter, until the Union-Square Theatre lost much of its local renown. Its accomplished director made, we believe, a serious blunder in turning his fine company loose upon this broad country, and especially upon all the small towns that lie between here and San Francisco. A great New-York company has its life and opportunity in New-York. However, the new management of the theatre appreciates a truth which should not have been lost sight of. The company of the Union-Square Theatre will hereafter belong to our City, not to the Western prairies. If, then, it is wisely directed, a certain and splendid popularity will be accorded to it. There is no reason, one is led to think, why such an intelligent organization should not be wisely directed. Its quality is high and fine; this means that plays of fine quality should be produced at the Union-Square Theatre, not plays which degrade public taste and discourage that large class of observers who find so little of worth, interest, and beauty upon the contemporary stage. It is surely as unsafe to take too low a view of popular taste as to take a too lofty and abstract view of it. A theatre can, with proper spirit and foresight, create and maintain its own standard of taste, its own public, its own traditions. This was shown practically in the record of the Union-Square Theatre until a few years ago; it has been shown as cogently in the establishment of two other local theatres. ___

New-York Daily Tribune (27 November, 1883 - p.4) MUSIC AND THE DRAMA. STORM-BEATEN. The presentation of character, wrought upon by experience and displayed in its development, under dramatic circumstances, would seem to be the proper object of theatrical literature and histrionic art. The best plays, certainly, are those which accomplish that result. Another kind of play—by no means the best, but sometimes effective and popular—is that which aims, simply and solely, to tell a story by means of stage pictures. Mr. Buchanan’s “Storm- Beaten” is a play of this kind. He made it out of one of his novels,—thus telling over again, through theatrical expedients, a tale that he had already told in narrative. It is a tale kindred with that of “The Frozen Deep,” and it makes much the same sort of a play. The chief person in it is a brave, chivalrous, resolute, intrepid young fellow, whose sister has been seduced and abandoned by a scoundrel, and who determines to pursue, and does pursue, her seducer, through many perilous scenes,—being resolved to kill him, but, at last, rejecting the opportunity of revenge, and giving a strong practical illustration of magnanimous charity. Squire Orchardson of the Willows ..... John Parselle ___

The New York Times (30 November, 1883) Mr. Steele Mackaye’s new folding theatre chair, which had its first trial on Monday night at the Union-Square, has thus far caused a good deal of amusement, not unmingled with indignation. The amusement rests with the people who are already seated, and is indulged wholly at the expense of those who are about taking their seats. Between the acts at the Union-Square this week there has been quite as much amusement as during the progress of the play. On Wednesday evening a TIMES writer, who went early and staid late, had ample opportunity to observe the interest created by Mr. Mackaye’s chairs. A gentleman came in with a lady, and when they had been shown to their chairs by the usher the gentleman politely drew down the seat and stepped back to let the lady pass. As soon as he removed his hand from the seat it quietly folded up. He seemed slightly surprised, and pushed it back again into the proper position for use. Again moving to one side to let his companion by he took the pressure off for an instant and up came the seat again. An unpleasant flush crossed his face. The narrow aisle was choked up with people, and the gentleman seemed to feel embarrassed at the thought that they were waiting for him. The lady nudged him in the back with her fan and asked him to hurry. He seemed rather warm and dropped his overcoat on the floor. Then pushing the seat into place again, he huddled himself to one side, stood on the garment, held the seat down, and the lady managed to squeeze past him. As soon as she was in position and just ready to sit down her escort withdrew his hand, no doubt for reasons of self- preservation. The seat immediately began its upward journey, while an expression of mingled amazement and horror crossed the lady’s face. Barely in time to avert results of a spectacular character, she thrust her hand behind her and hurriedly sat down. Her face was a brilliant carmine for some time, and throughout the evening she sat preternaturally still and obviously afraid to move. The gentleman sat down with a sigh of measureless relief and passed the most of the evening in uncomplimentary analyses of Mr. Mackaye’s invention. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (4 December, 1883 - p.5) QUEEN’S THEATRE. Storm Beaten, which was produced at the Queen’s Theatre last night, is a drama of an exceedingly sensational and exciting character. Its success depends upon special and elaborate scenery, as well as upon good acting, and, judging by the reception accorded to it, the impression created was of the most satisfactory kind. Some of the scenes are very striking, and the incidents of the story are depicted with much skill and success. During the performance the principal artistes were several times called before the curtain and loudly cheered. ___

The New York Times (9 December, 1883) There is no likelihood of an immediate change of programme at the Union-Square Theatre. Mr. Cazauran said yesterday that he thought “Storm Beaten” would run through the bulk of the season. When informed of rumors that the piece was soon to be taken off, he replied that the same sort of thing was invariably said of every new play produced at the Union-Square Theatre. “Why,” he declared, “when ‘Rose Michel’ was brought out Mr. Palmer came within an ace of taking it off after the first week. He was younger then at the business than he became before he finally left it, and he was consequently easily frightened by the general talk of failure. Well, ‘Rose Michel’ ran for three months to an average business of $900 a night. The Union-Square is a peculiar theatre. We have never been able to gauge the amount of success a production will receive until after the first two weeks. We can only guess at it by comparing the ledgers of the theatre, which, in the case of ‘Storm Beaten,’ show us that the receipts have up to date been considerably larger than those of any other play ever brought out here, for the corresponding period of time. Make your mind easy about ‘Storm Beaten.’ It will have a good run. If it should not finish the season it is probable—not positive, mind you, but only probable—that ‘La Justice,’ a French play imported by Brooks & Dickson, may follow it. There is nothing absolutely settled about that, and we do not even know how long ‘Storm Beaten’ may go.” ___

The Liverpool Mercury (11 December, 1883 - p.5) ALEXANDRA THEATRE. A drama full of human interest and strongly charged with poetic flavour is now being presented on the stage of the Alexandra Theatre, Liverpool, and on that of the Union-square Theatre, New York—the old world and the new thus uniting in recognition of the powers of an author who has long striven to attain a high position as a dramatist. By Robert Buchanan, the play is called “Storm-beaten,” and the performance at the Alexandra last night was the first that had taken place in this city. The piece enjoyed the warm approval of a large audience. Mr. Buchanan has chosen the melo-dramatic form for the conveyance of a moral lesson whose force is increased by the very sensationalism of the incidents which lead to the striking termination of “Storm-beaten.” It may be urged that the bases of the action have been used before, but their skilful application can be set against this objection. Retributive justice, the breaking of a revengeful spirit, and the restoration of a soothing peace have rarely been more emphasised on the stage than in Mr. Buchanan’s adaptation of his own romance ”God and the Man.” The prologue and the first and second acts prepare the way towards a quickening of the movement of the play, and as incident succeeds incident, the attention of the audience is maintained, not merely because the art of dramatic construction reveals itself, but because the writer of “Storm-beaten” has the faculty, given to so few, of expanding those sympathies whose exercise is fruitful of good. The comic portions of the play might easily be strengthened by condensation, and surely Mr. Buchanan is not aware of the fact that a song embracing imitations of the cat, the cow, and the parrot, is introduced by the daughter of Jacob Marvel while what is technically known as a front cloth—admirably painted—separates the village church from the Island of Desolation? The song with its imitations is cleverly sung, but its incongruity threatens the integrity of the play. The presence of summer foliage amid the snow and ice of the last scene of all is also a disturbing element. Regarded generally, the representation of “Stormbeaten” by the company engaged for the provincial tour is very satisfactory. Mr. Courtenay Thorpe and Mr. W. F. Lyon render with discretion Richard Orchardson and Christian Christianson, the men on whom rests the carrying out of the main purpose of the drama; Miss Kathleen O’Connor gives point to the part of Kate Christianson; and Miss Annie Robe as Priscilla Sefton plays a lovable character with much sweetness of expression. Other characters are successfully undertaken by Miss Letty Lind, Mrs. W. Forth, Mr. Charles Medwin, Mr. Harry proctor, Mr. Walter Scott, Mr. F. C. Duncan, Mr. A. J. Hilton, and Mr. James Elmore. “Storm-beaten” is to hold the stage of the Alexandra during the next seven nights. ___

The Era (15 December, 1883) HANLEY. THEATRE ROYAL.—Lessee, Mr James H. Elphinstone; Acting-Manager, Mr Charles G. Elphinstone.— _____

|

|

|

|

|

|

|