|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. When Knights Were Bold - Reviews, etc. (1) |

|

|

|

|

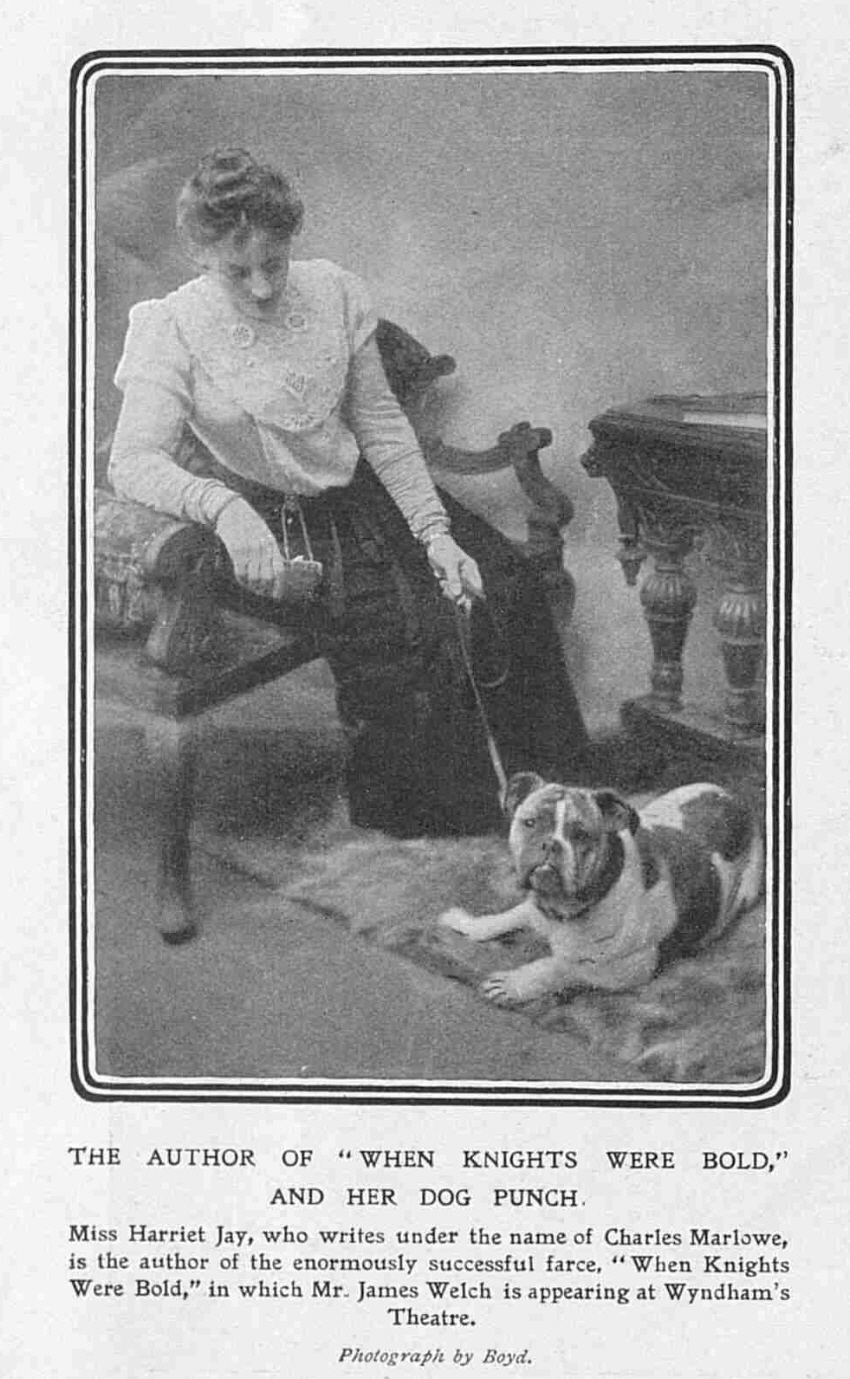

Act one.—“Forty winks.” Sir Guy’s Study (the Knight’s Room), date A.D. 1906. 700 years pass backwards. If rollicking fun counts for anything, When Knights were Bold should be successful. The author, or rather authoress, is “Charles Marlowe,” a pseudonym, which, as everybody knows, veils the identity of Miss Harriet Jay. In designing the piece Miss Jay has made remarkably smart use of an old idea—and a very ancient one at that—but there is nothing new under the sun, and in laughing at the absurdities and extravagances of When Knights were Bold one forgets that dream plays have been pretty plentiful these many years past. Without troubling to reflect further, the names of The Bells, Ma Mie Rosette, A Message from Mars, and To-morrow rise to the recollection, and of these the new farce most nearly approximates to the latter, both dealing with events and scenes of long ago. When Knights were Bold, however, lays itself open to no charge of plagiarism. Except in the sense that all farces are more or less alike in their boisterous exuberance, Miss Jay’s latest work is, in the manner of its unfolding, original enough. It will be all the better for some building up, particularly in the third act, which is extremely attenuated, and doubtless Mr. Welch’s fertile brain will ere long devise some means of strengthening the concluding portion of the play. ___

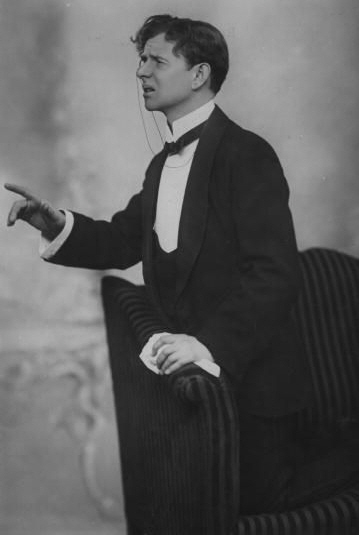

The Daily Telegraph (20 September, 1906 - p.7) A favourable reception was, according to the local critics, accorded to Miss Harriet Jay’s new farcical comedy “When Knights Were Bold,” produced by Mr. James Welch at Nottingham last Monday evening. The piece would seem to be of a boisterously amusing description, and Mr. Welch’s part of a kind well suited to his peculiar talents. At the close of the first act the hero is supposed to fall asleep and dreams that he has been transported back into mediæval England, through which he wanders, meeting with many strange and curious adventures, attired the while in modern evening dress. In the third act he is again in the twentieth century. But his experiences in dreamland have taught him a useful lesson, and, resorting to the more forcible methods of the thirteenth century, he succeeds in clearing his house of certain inconvenient visitors, and by so doing wins the hand of the lady who has hitherto regarded him as a singularly pusillanimous and timid wooer. The piece will in due course be presented at Terry’s. ___

The Mid-Sussex Times (25 September, 1906 - p.7) Miss Harriett Jay, whose comedy, “When Knights Were Bold,” has been produced at Nottingham by Mr. James Welch, is the sister of Mary Jay, the deceased wife of the late Robert Buchanan. It is rather over 20 years since she dawned on the literary world with an anonymous novel, “My Connaught Cousins,” which was at first attributed to Charles Reade, who spoke of the attribution as “the greatest compliment ever paid to me by the critical Press.” It was followed by “The Priest’s Blessing” and “Two Men and a Maid,” also published anonymously. Then the secret leaked out, and a girl scarcely out of her teens found herself one of the literary heroines of London. ___

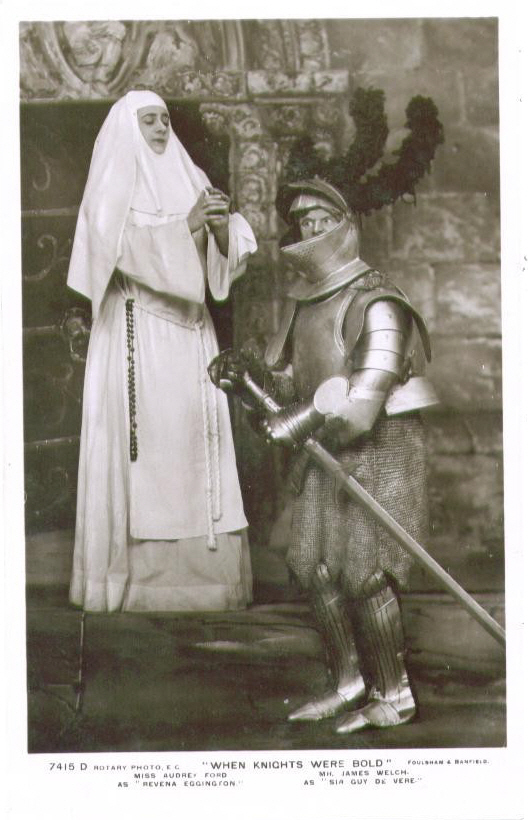

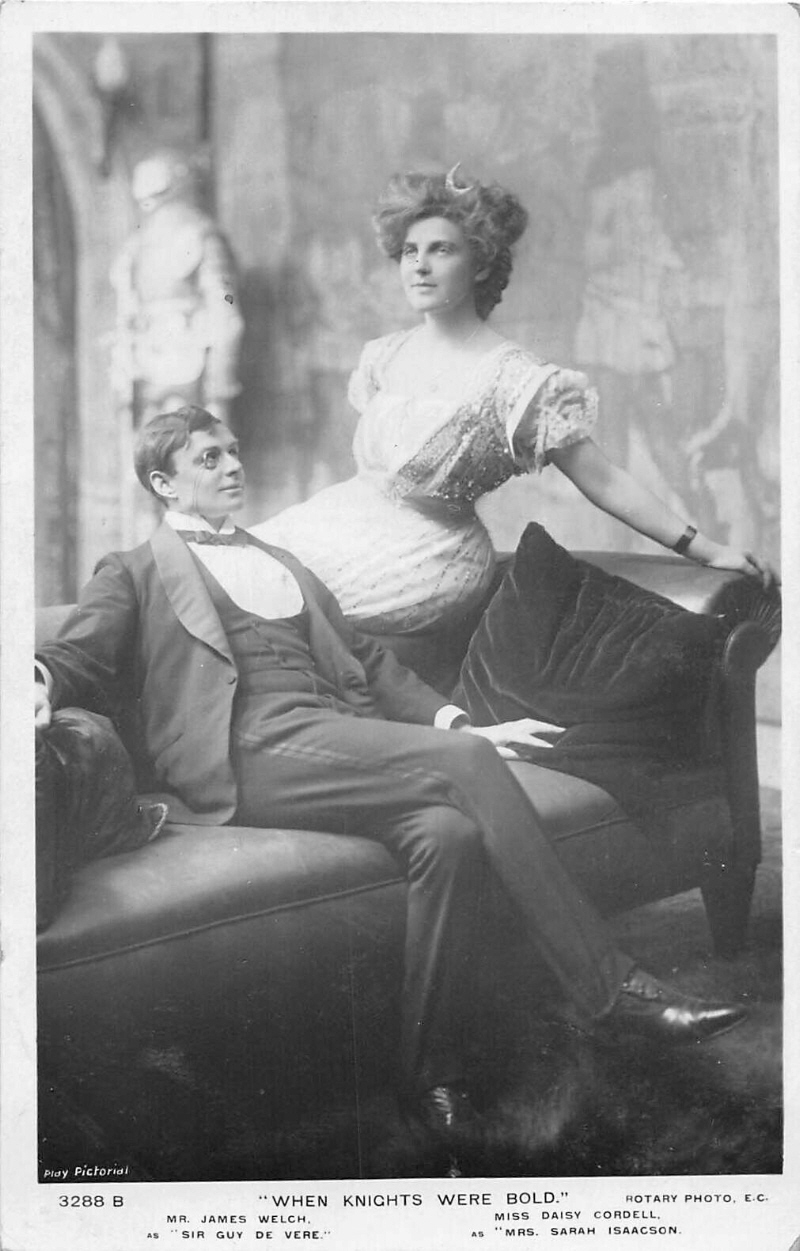

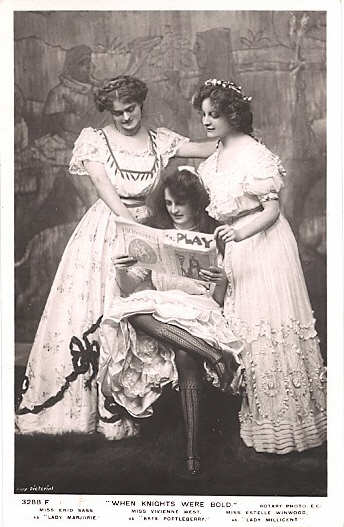

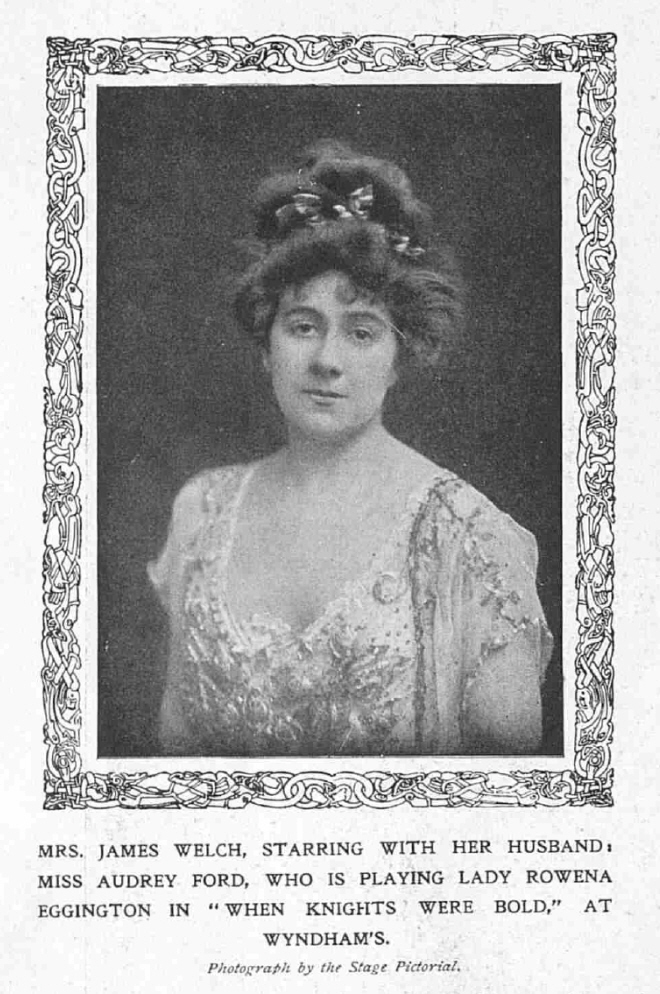

The Stage (4 October, 1906 - p.4) CARDIFF—ROYAL (Lessee and Manager, Mr. R. Redfred).—Mr. Redfred’s catering for the Cardiff public could not be excelled, what with Shakespeare’s works, musical comedy, and now this week an exceedingly funny and humorous comedy from the pen of Harriet Jay, When Knights Were Bold. Mr. James Welch, of New Clown fame, plays the principal part, and keeps the house in continual laughter. Miss Audrey Ford is admirably suited to the part of Rowena. Mr. Edward Sass is buoyant and cheery as the Irish baronet, Sir Brian Ballymote. Miss Daisy Cordell is well suited as Sarah Isaacson. Miss Enid Sass and Miss Mabel Wentworth are delightful in the ingenue parts. Miss Annie Chippendale lends admirable assistance as the Housemaid. Miss Emma Gwynne looks and acts well as Mrs. Waldegrave. Miss Estelle Winwood is a piquant Millicent. Mr. Gordon Tomkins is a Butler. Mr. Henry J. Ford is most humorous as Mr. Widdicombe; his song and dance are well appreciated in the second act. Mr. Arthur Grenville gives a finished performance of Isaacson. Mr. G. F. Tully, Mr. James Nelson, and Mr. Leopold Profeit are well placed in their parts. ___

The Guardian (20 November, 1906 - p.7) PRINCE’S THEATRE MR. JAMES WELCH IN A NEW FARCE. It is said that Mr. Welch is one of the comedians with an ambition to melt or to harrow us, but if it be so he does not make much headway against his destiny. And really those who saw him again last night will hardly be disposed to spare him for the serious drama. Nor can he, as some misjudged authors do, come out anonymously, for his personality is too distinguished for disguise. There is distinction in his acting of these wild farces, one of the wildest of which is Mr. Charles Marlowe’s “When Knights were Bold.” Perhaps the critic, who, after all, is supposed to maintain a sense of responsibility, is at some comparative disadvantage with this type of play, but we did not reason with our enjoyment last evening. Mr. Welch is always good, but from time to time he gets us under complete control, and the most frigid of us relaxes into the joy of laughter. He does it all very easily—too easily, perhaps, for, as the sportsman would say, he is never really extended except in a physical or vocal sense. Sometimes the members of his company laugh at him in the wrong places, but we may believe that he will forgive them. ___

Daily Express (9 January, 1907 - p.7) After “Toddles” at Wyndham’s—as announced in this journal yesterday—comes Mr. James Welch in his big provincial success, “When Knights Were Bold.” Part of this comedy has been re-written—the last act has been improved, and the piece generally strengthened. |

|

|||||

|

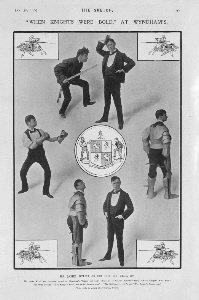

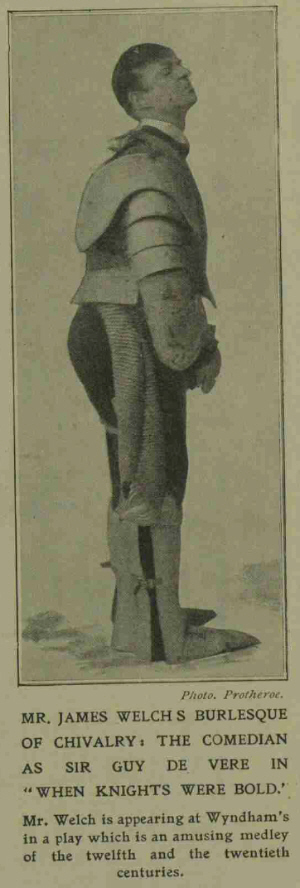

The Sketch (30 January, 1907 - p.5) |

|||||

|

|||||

|

(p.18) HEARD IN THE GREEN-ROOM IT is but seldom that an actor has the opportunity of playing in two pieces of the same name. That, nevertheless, might have been the lot of Mr. James Welch, for Miss Jay’s farcical comedy, “When Knights Were Bold,” was originally called “The Good Old Times.” That title happens, however, to have been applied to a play written by Mr. Wilson Barrett and Mr. Hall Caine in the days of old when Mr. Welch was a young member of the company of the famous actor-manager. It was therefore obviously impossible for him to use it. Of that play Mr. Welch tells an amusing incident. One scene took place on board a boat on a river between the characters represented by Mr. Barrett himself, Mr. Cooper Cliffe, and Mr. Robert Pateman. To convey the impression of movement, a panorama over a hundred yards in length was used. Unhappily, however, it did not run evenly, and at times it would come to a dead stop. To restart it, it was necessary to roll back several feet of the canvas, and then set the machinery going quickly in the proper direction, so as to get past the obstruction. This, as may be imagined, was always a source of great amusement to the audience. One night, when the voyage had been even less successful than usual, and Mr. Barrett could stand it no longer, he exclaimed, “I will get out here and meet you at the next point.” Suiting the action to the word, he got off the boat and walked to the next point—off the stage—and presumably on the surface of the water. ___

The Times (30 January, 1907 - p.6) WYNDHAM’S THEATRE. “WHEN KNIGHTS WERE BOLD.” |

|

|

|

|

|

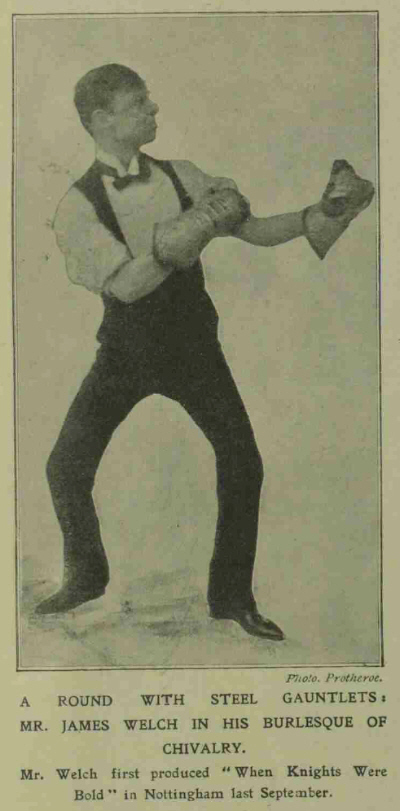

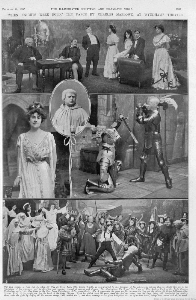

Act one.—The Knights’ Room, Beechwood Towers, 1906 (“Forty Winks”). 710 years pass backwards. Act two.— The Battlements, 1196 (“A Dream of ye Good Olde Times”). 710 years pass forwards. Act three.—The Knights’ Room. 1906 (“Wide Awake”). Mr. James Welch, who has not had a fixed local habitation in the West-End since his stay at Terry’s, during which he produced The Heroic Stubbs and A Judge’s Memory, and revived The New Clown, resumed operations in central London, at Wyndham’s, on Tuesday, when he presented When Knights Were Bold, a farce by Charles Marlowe (Harriet Jay) which has gained popularity on tour. When Knights Were Bold was produced at the Royal, Nottingham, September 17, 1906, and reached the Grand, Croydon, on the following October 29. At Wyndham’s Mr. Welch is again supported by Miss Audrey Ford and nearly all the members of the former cast, the company being fully capable of giving adequate interpretation to a Dream play that has a genuinely comic root idea, as contrasted with the tragic theme of The Bells, the didactic tendency of A Message From Mars, the pathetic interest of Uncle Dick’s Darling, and so on. Scott’s novel “Ivanhoe,” which has before now been treated seriously upon the stage, has formed the groundwork of Miss Harriet Jay’s farce, and several of the characters of the book re-appear, mutatis mutandis, in the play. Thus Sir Walter’s hero becomes a very modern young man of ancient lineage, Sir Guy de Vere, with an ultra-romantic cousin in Rowena Eggington, who is continually dinning into his ears the doughty deeds of the former chivalrous occupants of the Knights’ Room at Beechwood Towers. Again, Rebecca and her father, Isaac of York, find re-incarnation in Sarah Isaacson and her sire, Isaac Isaacson, a Throgmorton-street financier. The Dean of Beechwood, the Rev. Peter Pottleberry, D.D., stands for Peter the Monk; the Seneschal is replaced by Barker the butler; the Jester is represented by Charles Widdicombe, a would be funny man; and the bold, bad Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert is transformed into a boastful and card-sharping adventurer of an Irish baronet, Sir Brian Ballymote. Made quite sick of the glorious past by the lucubrations of Rowena, Sir Guy, in 1906, turns for a change to Miss Isaacson, whose father regards him as an excellent match; and, similarly, the neglected Rowena begins to find Sir Brian an agreeable companion. Tired out by the doubtful enjoyment of a day’s shooting in the rain, and suffering from a bad cold, Sir Guy drops off to sleep in his study so full of ancient memories, the Knights’ Room, and in his dream things become much as they were 710 years back, the time 1196 being specified. The young baronet is surrounded by mediæval retainers in gay costumes and coats of mail, this second act taking place upon the Ramparts. Here, with Sir Guy still wearing at first the evening dress in which he fell asleep, some funnily incongruous events take place. The romantic Rowena of the opening ought to have had her heart’s desire satisfied, for she becomes a novice, persecuted by Sir Brian, and her appeal to Sir Guy to rescue her leads up to a burlesque duel, both knights being now clad in shining armour, until Sir Guy finds “mailed fists” more efficacious. Further, the twentieth century Isaacsons are plunged back into the dangers that of old beset their race in England before their expulsion by Edward I., for, in their former manifestations as Isaac of York and Rebecca, they are made captives in one of the deepest dungeons of the Towers, and are threatened with torture and a fearful death by a Jew-baiting monk, who here takes the place of the accommodating Pottleberry. Hoping to be rescued herself, Rowena is again adept in the art of “egging on,” this time against the unfortunate Hebrews, and Sir Guy’s posturing in the rôle of their valiant defender makes an effective scene. The working out takes place in act three, which was originally rather weak. Seven hundred and ten years pass forward and Sir Guy is once more found “wide awake” in his study, in 1906, the baffling of Sir Brian and the winning back of Rowena’s temporarily-lost affections being the main points aimed at by the authoress. As Sir Guy arises from his dream he is heard shouting “Victory!” and seen belabouring an ancestral suit of armour. The affright of all the household makes him determine to give them “the good old times” in earnest, the dreadfully modern and slangy young man of act two becoming a turbulent, scowling, mouthing creature. Then Rowena begins to get weary of the past herself, and the cowardice of Sir Brian in refusing to “tackle” an apparently raving lunatic puts him out of court with her, his discomfiture being completed by his being proved to have cheated at bridge, and to have plotted with Isaacson to have secured Rowena for his wife. ___

The Illustrated London News (2 February, 1907 - p.14) |

|

|

||

|

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (2 February 1907 - p.7) LATE THEATRES. “WHEN KNIGHTS WERE BOLD,” AT WYNDHAM’S. THE dream-play, perhaps because it is ex hypothesi so little convincing in its action, has fallen in these prosaic realistic days somewhat out of fashion. For anything like serious sentiment its scheme is no doubt not too well suited, but, after all, it fits in very fairly with the requirements of farcical fun, such as that expected of a comedian like Mr. James Welch. So, at any rate, seems to have thought the lady who, writing under the pseudonym of Charles Marlowe, has made the hero of her play Sir Guy de Vere, Bart., dream very amusingly indeed. What kind of vision it is that Sir Guy experiences may be guessed from the fact that while enjoying forty winks in the Knights’ Room of Beechwood Towers in 1906, he is transported to those “days of old” when, on The Battlements, in 1895, there was a call for deeds of chivalry very unlike any demanded of the “warrior bold” of to-day. As set forth in the second act—after a backward lapse of 710 years—these deeds have been found so mirth-provoking in the provinces, that with the aid of Mr. Frank Curzon, Mr. Welch has found at Wyndham’s a stage for them in London, where on Tuesday evening they were received with shouts of laughter, which seem likely to echo for many weeks to come. ___

The Observer (3 February, 1907) “WHEN KNIGHTS WERE BOLD” AT WYNDHAM’S. For young gentlemen asked to bring their music with them to evening parties “The Warrior Bold” used some years ago to be a favourite, and indeed an almost inevitable, selection. Many of us when listening to Stephen Adams’s martial strain as carolled forth by the reedy voice of a weedy youth must have been struck by the delightful incongruity of the performance; and it is this incongruity which seems to have suggested to Mr. Charles Marlowe—otherwise Miss Harriet Jay—the motive of her farce “When Knights were Bold.” Take a small, insignificant, red-headed baronet with an ancient lineage and a modern dinner jacket; place him amongst his armoured retainers of the days of old; make him pipe out the ringing defiance of a Crusader with the whine of a Cockney accent; let him protect maidens in distress less acute than his own, fight the good fight in a singularly uncomfortable cuirass, and burlesque in the slangy realism of to-day the formal chivalry of a day gone by. You will then have the notion of the joke of incongruity which at Wyndham’s Theatre now has Welch in Armour for its central figure. It is a capital joke so far as it goes, though it does not go quite far enough to save from tedium a long first act of preparatory explanation and a shorter third one of perfunctory rectification. If, however, Sir Guy de Vere is rather a dull little dog as the host of a noisy house party at Beechwood Towers in 1906, he is such a droll dog on the battlements of Beechwood Towers in 1196 that he seems certain to draw all mirth-loving London to laugh over his comicalities. He is so funny when he is dreaming that one forgives him for being a trifle tiresome when he is awake, and one may certainly do worse than drop in at Wyndham’s for an hour at half-past nine or so just to enjoy Mr. Welch’s vision of mediæval valour without troubling much about either its cause or its effect. He works tremendously hard over it and makes quite the most of possibilities which would have been much greater if Sir Guy’s nightmare had been less consistent in remaining mere horseplay after all. His most useful supporter is Miss Audrey Ford, whose travesty of the high-flown romance of a twentieth century Rowena is very good indeed. ___

The People (3 February, 1907 - p.4) WYNDHAM’S. Mr. James Welch, after an absence on tour, reappeared last Tuesday in a piece, new to London, by a lady playwright, who elects to be known as “Charles Marlowe.” The production, entitled “When Knights were Bold,” is a farce giving Mr. Welch the opportunities of which he takes full advantage of impersonating the “tenth transmitter of a foolish face,” an inane baronet whose talk is the slang of the gutter, and whose manners ape those of the stable. Such conduct displayed by Sir Guy de Vere at his own ancestral towers shocks and horrifies the prudes and prigs at the other extreme of social propriety, representing the relatives and neighbours among whom his country life is cast. The continuance of this tiresome society contrast throughout the first act, displaying Sir Guy as a tedious bore while awake, is happily relieved in the second when he falls asleep, and escapes—and the audience with him—from his prosaic present to his romantic past in dreamland. Seven centuries roll back in his vision to the days of Cœur de Lion, and Sir Guy stands in his own castle, surrounded by the intimates of his waking hours. It is here that the fun, and with it the farce, really begins. For while the knight retains his modern habiliments the rest of the castle residents are arrayed in complete panoply of the mediæval past, the society joker as a tomfool, the reverend rector as a hooded monk, the haughty lady cousin as a devout nun, and the testy Irish visitor as a bold baron. The company paralyse with charm their astounded host by banning him as a magician, shrinking back in consternation when he strikes a match alight upon his trousers. The laughter at this and similar anomalous anachronisms rises to a loud peal when the fire-eating Irish baron, taking offence at his host, challenges him to a duel, and the knight in sheer fright submits to his friends arming him for the fray as they enclose the little man in the suit of mail ludicrously masking his modern dress clothes. Plucking up courage as he stands forth to do wager of battle, Sir Guy incites a roar of hilarity by wriggling out of his cumbersome breastplate and gauntlets and pummelling his astounded challenger with his bare fists. The fun ends with the dream, for in the ensuing act Sir Guy, found awake again, is seen at the close of action lacking comic significance to be finally transmated into a respectable representative of his ancient lineage. ___

The Sketch (6 February, 1907 - p.10) THE STAGE FROM THE STALLS. . . . The reappearance of Mr. James Welch at Wyndham’s Theatre was very welcome, and there was a hearty round of applause when he came on as the dapper little Sir Guy de Vere. Since he is supposed to belong to an ancient and honourable family I do not know why he chose to adopt a rather common style, that no doubt enhanced the humours of a remarkably clever comic performance, yet seemed outside the scheme of the play; possibly his answer would be that “When Knights were Bold” is only a scheme, and not exactly a play, and that he was therefore entitled to a free hand. This sounds very true; regarded as a play, the work of “Charles Marlowe” is naught, but it gives one of our cleverest and most fertile low-comedians a capital opportunity of showing his capacity for entertaining an audience by the hour. Worshippers of music-hall stars, when comparing them with performers in the legitimate and explaining their failure in the ordinary theatres, point out that their work is essentially self-centred and intensely concentrated—that they put the whole vitality of a day into a few minutes, and are at sea when asked to spread their work over a couple of hours or so. Mr. Welch showed the intensity of work typical of the music-hall artist, but he spread it over two hours and a half without obvious diminution of intensity. It was, I think, the most wonderful piece of sustained high-pressure acting that I recollect, and everywhere marked by clever little bits of “business,” by skill in execution that gave a pleasure to the critical entirely apart from the dramatic value of the performance. Moreover, the author has given full scope for wild fun in the act where the twentieth-century degenerate, with a spark of warm blood in him, finds himself back in the times of the peculiarly un-English king, Richard Cœur de Lion, and endeavours, despite his modern ideas, to accommodate himself to the brutal manners of the twelfth century. Among those who supported Mr. Welch it is but fair to mention Miss Audrey Ford, quite effective as his sweetheart; Miss Daisy Cordell, and Messrs. H. J. Ford and G. F. Tully. |

|||

|

|

The Illustrated London News (9 February, 1907 - p.37) “WHEN KNIGHTS WERE BOLD,” “When Knights Were Bold,” a farce written by “Charles Marlowe” and recently produced at Wyndham’s Theatre, is a stale and rather dreary specimen of the mock-heroic play. While the basis of the play is the contrast between the diminutive stature and frail physique of a young Baronet of the present year of grace and the chivalric notions associated with hi title of Sir Guy de Vere, the author gets no nearer carrying through this idea than by making her ultra-modern and puny hero overcome his love-rival by fisticuffs in a dream, which takes the action back seven hundred years; and then, when the awakening comes, order this adventurer out of the house on a charge of cheating at cards. The main difference between Mr. James Welch and Mr. Weedon Grossmith in this kind of unromantic rôle consists in the fact that Mr. Grossmith represents Cockney as opposed to “genteeler” humour, and assumes a certain imperturbability for which Mr. Welch’s substitute is a degree of nervous vigour. Frankly, however, we are little more impressed by the leading player’s performance in Miss Jay’s farce than by the play itself. Mr. Welch, as the Sir Guy who loathes the very mention of the “days of old,” has little more to do in the first act than to sneeze in the face of the other characters, and even in the play’s final passages, where the baronet feigns madness in a mood of reincarnate knighthood, the author’s scheme allows the actor but few amusing moments. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

“WHEN KNIGHTS WERE BOLD” MISS ENID SASS MISS VIVIENNE WEST MISS ESTELLE WINWOOD

The Daily Mirror (16 February, 1907 - p.8) “A BOLD KNIGHT” MR JAMES WELCH A COMEDIAN HARASSED BY MANUSCRIPTS. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (16 February, 1907 - p.21) |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (23 February, 1907 - p.18) OUR CAPTIOUS CRITIC. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

The Sketch (27 February, 1907 - p.18) |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

The Daily Telegraph (11 March, 1907 - p.9) QUEEN AND DOWAGER-EMPRESS. . . . On their way back through the City from Whitechapel to Buckingham Palace, the Queen and the Empress Maria Feodorovina paid a brief visit of inspection to St. Paul’s Cathedral. In the evening their Majesties were present at Wyndham’s Theatre, and witnessed the performance of “When Knights were Bold.” ___

The Daily Telegraph (1 April, 1907 - p.11) EASTER AMUSEMENTS. . . . “When Knights were Bold,” at Wyndham’s, has established itself as one of the successes of the season; as an enjoyable specimen of rollicking fun it would indeed be hard to beat. The second act, in particular, keeps the audience in a constant state of laughter from the moment of the rising of the curtain to its fall. Mr. James Welch is, of course, the life and soul of the entertainment. He it is who, falling asleep in the twentieth century, suddenly discovers that he has strayed into the fourteenth, to whose customs and usages he is called upon unwillingly to subscribe. The situation is ludicrous in the extreme, and of it Mr. Welch makes the most. Those who desire a couple of hours’ continuous diversion cannot do better than repair to Wyndham’s. ___

The Illustrated London News (20 April, 1907 - p.2) “A BOATSWAIN’S MATE,” AT WYNDHAM’S. A CHARACTERISTIC instance of Mr. W. W. Jacobs’ genial, irresistible humour, full of laughable situations and neat portraiture, is the little one-act play adapted by Mr. H. C. Sargent and the author from Mr. Jacobs’ short story entitled “A Boatswain’s Mate.” The scene of the piece, of course, is a rural inn, and there is an attractive landlady to gain whose affection the sailorman hero of the tale resorts to stratagems. Every reader of Mr. Jacobs’ stories knows how invariably those stratagems of his enamoured captains or mates or boatswains go wrong, and last Monday night’s audience at Wyndham’s, to which the play was first introduced, was fully prepared to find that the boatswain’s idea of getting a discharged soldier to pretend to “burgle” the bar so that to the sailor might fall the distinction of effecting a rescue would be foiled by some unexpected contingency. In point of fact the landlady, so far from feeling timorous, proves an Amazon, and after many droll complications it is the soldier and not the boatswain who wins the lady’s heart. Very happy is Mr. Tully in the rôle of the rollicking soldier who volunteers to be the boatswain’s ally, and if Miss Ethel Hollingshead fails somewhat to suggest the landlady’s unctuous vulgarity; if, too, Mr. W. E. Richardson does not vary sufficiently the oddities of the boatswain, both work hard for a farce that almost acts itself. “A Boatswain’s Mate” is played in front of Charles Marlowe’s fantastic comedy, “When Knights Were Bold,” in which Mr. James Welch still figures in the leading part. [Note: W. W. Jacobs is probably best known today for his short story, ‘The Monkey’s Paw’, which has been filmed several times, and I make no apology for recommending this particular adaptation: Jenny Ringo and the Monkey’s Paw.] ___

The English Illustrated Magazine (June, 1907) “When Knights were Bold” at Wyndham’s Theatre presents a very good example of the finishing process which, in our day, is so frequently postponed till after the pulse of an audience has been felt at a few public productions. Especially if a play is a farce, the comedian who is its mainstay rarely feels the full capabilities of his part on the first or second night. Mr. James Welch, if not “a fellow of infinite jest,” has imagination, invention and humour, and he has applied all these qualities to getting a good deal more fun out of the part of Sir Guy de Vere than was apparent in the early days of the production. Of course, there comes a smile to the lips at the mere suggestion of Mr. James Welch impersonating the modern representative of a long line of august and haughty ancestors. Knowing his methods as we do, we foresee the broad humour of the contrast he will give us, his banal modernity, his outrageous violations of all the sacred traditions of his House—all the trebly-panoplied reserve of aristocratic prejudice. Sufficient to say that he realises our anticipations. His Sir Guy de Vere is neither sturdy oak nor polished rosewood; it is very plain deal with no superficial veneer even. He is a plague, a thorn, a monstrous idiosyncrasy in the view of the other and normal de Veres. The antagonism is most diverting, but a little of it goes a long way, and too much is apt to become tedious without great inventive ingenuity on the part of the author in providing diversity of situation, and that ingenuity Mr. Charles Marlowe has not sufficiently shown. The first act dragged a little towards its close in the early days of the play, but it goes better now. It has been tightened, and Mr. Welch has filled it out with a broader appreciation of its possibilities, and the play being a farce these liberties are justified. The second act is pure burlesque, the visual representation of a dream. Sir Guy is no longer in the twentieth century but in the twelfth. He is still in garb and speech and habits of thought and action a modern, but all his surroundings, his relations and friends, the very atmosphere of life about him, are of the time of Richard the Lion-hearted. The fun becomes uproarious, the absurdities side-splitting. Then in the last act we have Sir Guy awake again, but retaining so vivid an impression of the topsy-turvy drama of his dream that now the incongruity is shifted from him to his environment. He still breathes the air of a mediæval England, and his relations and friends are hopelessly modernised. Such is the frame-work of “When Knights were Bold,” on which has been draped so many grotesque and laughable fantasies, that it becomes a kind of summer madness, not a thing to be written of seriously. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

[From The English Illustrated Magazine (July, 1907).] |

||||||||||||

|

|

[From The Sketch (24 July, 1907 - p.18).] _____

3. When Knights Were Bold - Reviews, etc. (August, 1907-1909) or back to When Knights Were Bold main menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|